Seki Takakazu facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Seki Takakazu

|

|

|---|---|

Ink painting of Seki Takakazu, from the Japan Academy archives in Tokyo.

|

|

| Born | 1642(?) |

| Died | December 5, 1708 (Gregorian calendar) |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Other names | Seki Kōwa |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics |

Seki Takakazu (関 孝和, c. March 1642 – December 5, 1708), also known as Seki Kōwa (関 孝和), was a brilliant Japanese mathematician and writer during the Edo period.

Seki helped create the foundation for what became known as wasan, which is Japanese mathematics. People have even called him "Japan's Newton" because of his important discoveries.

He invented a new way to write down algebraic problems. He also worked on calculus and Diophantine equations, which are special math problems, often to help with astronomy. Seki worked independently, even though he lived at the same time as famous European mathematicians like Gottfried Leibniz and Isaac Newton. His students later continued his work, and his ideas were very important in Japanese mathematics until the end of the Edo period.

It's not always clear which discoveries were Seki's own, as many appeared in his students' writings. However, some of his findings were similar to or even came before those discovered in Europe. For example, he is believed to have discovered Bernoulli numbers. He is also credited with the ideas of the resultant and determinant in algebra.

Contents

Seki's Life Story

We don't know a lot about Seki's personal life. He was likely born in either Fujioka or Edo (which is now Tokyo). His birth year is thought to be between 1635 and 1643.

Seki was born into the Uchiyama family but was later adopted into the Seki family. While working for a local ruler, he helped with a surveying project to create a good map of the land. He also spent many years studying old Chinese calendars from the 13th century. This was to replace the less accurate calendar used in Japan at the time.

His Amazing Math Career

Learning from Chinese Math

Seki's math, and wasan in general, was built on mathematical knowledge from China between the 13th and 15th centuries. These Chinese works included algebra with ways to solve problems using numbers, polynomial interpolation (finding missing values in a sequence), and equations with unknown whole numbers. Seki's work was often based on these older methods.

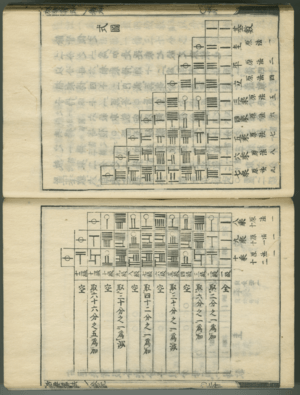

Chinese mathematicians found ways to solve complex algebraic equations with real numbers. They also used the Pythagorean theorem to turn geometry problems into algebra. However, they could only work with a few unknown values at a time. They used arrays of numbers to write formulas, like `(a b c)` for `ax^2 + bx + c`.

Later, they used two-dimensional arrays, but these were still limited to four variables. So, Seki and other Japanese mathematicians wanted to create ways to solve algebraic equations with many variables.

Chinese methods for polynomial interpolation were used to predict how planets and stars moved based on observations. This method also helped find different math formulas. Seki learned this technique, probably by carefully studying Chinese calendars.

Competing with Other Mathematicians

In 1671, a mathematician named Sawaguchi Kazuyuki published a book called Kokon Sanpō Ki. This book explained Chinese algebra in Japan for the first time. He used it to solve problems that other mathematicians were working on. At the end of his book, he challenged others with 15 new problems that needed equations with many variables.

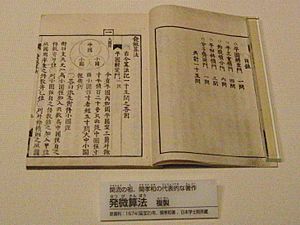

In 1674, Seki published Hatsubi Sanpō, which gave solutions to all 15 problems. He used a method called bōsho-hō. He also started using kanji (Japanese characters) to represent unknown values and variables in equations. His system could handle equations of any degree (he once worked with a 1458th-degree equation!). However, it didn't have symbols for things like parentheses, equality, or division. For example, `ax+b` could mean `ax+b=0`. Later, other mathematicians improved this system, making it as powerful as the ones in Europe.

In his 1674 book, Seki only showed the final equations after solving them, not how he got there. There were also some mistakes in the first version. Another mathematician criticized his work, saying only three out of 15 problems were correct. To respond to this, in 1685, Takebe Katahiro, one of Seki's students, published Hatsubi Sanpō Genkai. This book explained in detail how Seki solved the problems using his new algebraic symbols.

This new way of writing math helped mathematicians express their ideas in a more general and abstract way. They focused on how to get rid of variables in equations.

Understanding Elimination Theory

In 1683, Seki made big progress with elimination theory in his work Kaifukudai no Hō. This theory helps solve systems of equations by removing variables. To do this, he developed the idea of the determinant. While an early version of his formula for 5x5 matrices was wrong, a correct and general formula appeared in his later book, Taisei Sankei, which he wrote with Katahiro Takebe and his brothers.

Another mathematician named Tanaka Yoshizane came up with a similar idea on his own. In his book Sanpō Funkai (around 1690), he clearly described the resultant and used it to solve problems. In 1690, Izeki Tomotoki, another mathematician, published Sanpō Hakki. He also gave the resultant and a formula for the determinant for any size of matrix. It's not clear how these different works influenced each other. Seki developed his math while competing with other mathematicians in Osaka and Kyoto, which were important cultural centers in Japan.

Seki's early work on determinants was as early as Leibniz's first ideas in Europe. This topic was forgotten in the West until Gabriel Cramer rediscovered it in 1750. Elimination theory, similar to Seki's, was rediscovered by Étienne Bézout in 1764. The general formula for determinants was not established in Europe until after 1750.

With elimination theory, many problems from Seki's time could be solved, especially since Chinese geometry was often turned into algebra problems. In real life, this method could be very complicated to compute. However, this theory greatly influenced how wasan developed. After removing variables, the goal was to find the numerical solutions to a single-variable equation. Horner's method, a way to solve equations, was known in China but not fully passed on to Japan. So Seki had to figure it out himself. He also suggested a way to improve Horner's method by ignoring smaller terms after a few steps. This is similar to the Newton–Raphson method, but Seki had a different way of thinking about it. He and his students didn't have the exact idea of a derivative.

Seki also studied the features of algebraic equations to help solve them with numbers. One important discovery was how to find if an equation had multiple roots (solutions) using the discriminant. His idea of a "derivative" was based on how a function changes when a small value is added to its variable, which he figured out using the binomial theorem.

He also found ways to estimate how many real solutions a polynomial equation had.

Calculating Pi

Another important thing Seki did was to calculate pi (π), which is the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter. He found a value for π that was correct to 10 decimal places! He did this using a method now called the Aitken's delta-squared process, which was rediscovered much later in the 20th century.

Seki's Legacy

An asteroid named 7483 Sekitakakazu is named after Seki Takakazu, showing his lasting impact.

Selected Works

Seki Takakazu wrote many important math books. Here are a few:

- 1683 – Kenpu no Hō (驗符之法)

- 1712 – Katsuyō Sanpō (括要算法)

- Seki Takakazu Zenshū (關孝和全集), which is a collection of all his works.

Gallery

See Also

In Spanish: Seki Kōwa para niños

In Spanish: Seki Kōwa para niños

- Sangaku, which are mathematical problems carved on wooden tablets and displayed at Shinto shrines

- Soroban, a Japanese abacus

- Japanese mathematics

- Napkin ring problem