Serpent Mound facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Great Serpent Mound

|

|

The Great Serpent Mound – ancient Native American effigy in Adams County, Ohio

|

|

| Nearest city | Peebles, Ohio |

|---|---|

| NRHP reference No. | 66000602 |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

The Great Serpent Mound is a huge, snake-shaped hill built long ago by Native Americans. It is 1,348 feet (411 meters) long and about three feet high. You can find it in Peebles, Ohio.

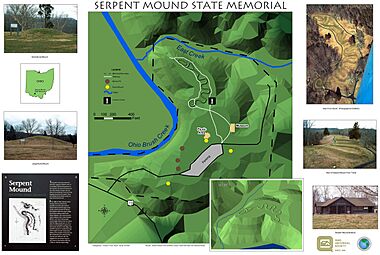

This amazing mound sits on a special plateau near the Ohio Brush Creek. It is the biggest snake-shaped earthwork known anywhere in the world!

Two explorers, Ephraim G. Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis, first wrote about the mound in 1848. Their book, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, was a big deal.

In 1966, the United States government named the mound a National Historic Landmark. Today, the Ohio History Connection helps take care of this important place.

Contents

What is the Great Serpent Mound?

People from many different cultures have built earthworks shaped like animals. These are called effigy mounds. The Great Serpent Mound is special because of its huge size and long history.

The mound is made of three main parts and stretches over 1,376 feet (419 meters). It is between 9 inches and over 3 feet (30–100 cm) tall. The width of the mound is usually between 20 and 25 feet.

The Serpent Mound follows the shape of the land. It was built on a high cliff above the Ohio Brush Creek. The snake-like shape winds back and forth for more than 800 feet. Its tail coils around seven times at the end.

The mound is mostly made of yellowish clay and ash. A layer of rocks and soil helps keep its shape.

The Serpent's Head and Tail

The head of the serpent looks like it has an open mouth. It almost swallows a hollow oval shape that faces east. This oval is 120 feet (37 meters) long.

Some people think the oval is an egg that the snake is eating. Others believe it shows the Sun or even a frog. Some scholars also think it might be what's left of a flat-topped mound.

On the western side of the mound, there is a triangular shape. It is about 31.6 feet (9.6 meters) wide at its base. This shape reminds some people of other snake mounds found in Canada and Scotland.

Who Built the Serpent Mound?

For a long time, experts argued about which ancient people built the Serpent Mound. It was a big mystery!

In 2014, new research using radiocarbon dating suggested the mound was built by the Adena people. This was around 300 BCE, which is about 2,300 years ago. The research also showed that the Fort Ancient people might have fixed up the mound around 1400 CE.

More studies in 2019 supported these ideas. They confirmed the mound was built by the Adena people between 2,100 and 2,300 years ago. They also found it was likely repaired by the Fort Ancient people about 900 years ago (around 1100 CE).

However, not everyone agrees. In 2018, archaeologist Brad Lepper questioned if the Adena people really built it. He pointed out that some of the dating methods might not be perfect.

Lepper and others noted that the Adena culture usually didn't build animal-shaped mounds. They also didn't often use snake symbols in their art. But the Fort Ancient culture did build the Ohio Alligator Mound and often showed snakes in their art. This suggests the Fort Ancient people might have been the original builders.

There's another snake mound in Canada, near Rice Lake. It's also over 2,000 years old and has been linked to the Adena culture. It's a zigzag shape that might be a serpent.

Ancient People of Ohio

Long before the Adena and Hopewell cultures, groups of Paleo-Indians lived in Ohio. This was from about 13,000 BCE to 7,000 BCE. They were hunter-gatherers, meaning they hunted animals and gathered plants for food.

These early people hunted large animals like mastodons. Archaeologists have found remains of over 150 mastodons in Ohio! They also found Clovis point spearheads, which were advanced tools.

Later, during the Woodland Period (800 BCE–1200 CE), people in Ohio started building earthworks and mounds. Many of these mounds were used for burials. People also began to farm crops like maize (corn), squash, and beans.

The Adena and Hopewell cultures grew during this time. Farming helped their populations grow a lot. Many Woodland people lived in larger villages, sometimes with walls for protection.

During the late prehistoric period (900 CE–1650 CE), villages became even bigger. They were often built on high ground near rivers and surrounded by wooden fences. Some cultures started building earthworks and effigy mounds again, but not as often as before.

Meet the Mound Builders

The Adena Culture: Early Mound Builders

The Adena culture was made up of Native American groups who lived in the Midwest. This included parts of Kentucky, Indiana, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and mostly Ohio. They lived during what is called the Early Woodland Period, from about 800 BCE to 1 CE.

The name "Adena" comes from an old burial mound found on the estate of Ohio Governor Thomas Worthington. He called his estate "Adena," which he said meant "delightful situation." This mound, which was 26 feet tall, was later destroyed for farming.

Archaeologists use the name "Adena culture" to describe groups who shared similar tools, building styles, and customs. This helps them tell these people apart from other cultures.

The Adena people were hunter-gatherers. Women also grew crops like squash, sunflowers, and tobacco. They often lived in small villages with gardens. They moved around to follow animal herds and find nuts, fruits, and roots.

The Adena people were also known for making clay pottery. They were among the first to bring pottery to Ohio. Their pottery was usually large, thick-walled bowls. Experts think they used these bowls to cook ground seeds into a soft, oatmeal-like food.

Adena Burial Practices

The Adena people buried their dead in large mounds across the Midwest. Many archaeologists believe these mounds also marked their territory. Often, small circular earthen areas were built near the mounds. These might have been used for special ceremonies.

The Miamisburg Mound in Montgomery County, Ohio, is the biggest Adena burial mound in the state. These mounds often held many burials. People were buried with special items like bracelets, ear spools, and gorgets (necklaces). Larger items like bones and stone tools were also worn around the neck.

Sometimes, the deceased were cremated. Other times, they were placed on their backs in tombs made of timber.

Around 1 CE, the Adena culture began to change. Their way of life slowly became what we now call the Hopewell culture. These new groups built even larger earthworks and traded for special materials like copper and mica.

The Fort Ancient Culture: Later Builders

The Fort Ancient Culture refers to Native American groups who lived near the Ohio River valley. They thrived from about 1000 CE to 1750 CE. You can find their ancient homes in southern Ohio, northern Kentucky, southeastern Indiana, and western West Virginia.

These tribes are sometimes called a "sister culture" to the Mississippian culture. However, they lived at different times and had many unique customs. Experts believe the Fort Ancient Culture was not directly related to the earlier Hopewellian Culture.

Even though many people think so, the Fort Ancient tribes probably didn't build the Great Serpent Mound originally. But they did help keep it in good shape around 200 CE.

The Fort Ancient Site

The culture gets its name from the Fort Ancient archaeological site. This site is on a hill above the Little Miami River, near Lebanon, Ohio.

Most archaeologists now think the Ohio Hopewell people built the Fort Ancient site. The Fort Ancient culture then used it later. Despite its name, experts don't believe it was mainly a fortress. They think it was more likely a place for ceremonies.

In 1996, a team of researchers found some pieces of charcoal at the Serpent Mound. They used carbon dating to find out how old the charcoal was. Two pieces were from around 1070 CE. This would place the Serpent Mound in the time of the Fort Ancient culture.

Another piece of charcoal was much older, from about 2920 years ago. This suggests the mound might have been built much earlier, possibly by the very early Adena culture or even before.

Another animal-shaped mound in Ohio, the Alligator Effigy Mound, was also dated to the Fort Ancient period.

Protecting This Amazing Site

The book Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley made many people interested in the mounds. One person was Frederic Ward Putnam from Harvard University. He studied the Ohio mounds, especially the Serpent Mound.

In 1885, Putnam visited the Midwest. He saw that farming and building were destroying many mounds. This meant important history was being lost. In 1886, with help from wealthy women in Boston, Putnam raised money. He bought 60 acres (240,000 square meters) of land around the Serpent Mound. He wanted to make sure it was protected.

The land he bought included the Serpent Mound, three cone-shaped mounds, an old village site, and a burial ground. Today, National Geographic Magazine calls the Serpent Mound a "Great Wonder of the Ancient World."

The Peabody Museum first owned the land. In 1900, it was given to the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society. This group is now called the Ohio History Connection. From 2010 to 2021, another group helped manage the site. But since March 2021, the Ohio History Connection has been in charge again.

After some damage in 2015, more security cameras and gates were added. This helps keep the site safe.

Digging Up History: What We Found

During digs at the Serpent Mound, archaeologists found many interesting things. They uncovered pipes, spear points, and earspools from the Hopewell culture. They also found gorgets (necklaces) and points from the Adena culture.

After buying the land, Putnam returned in 1886. For four years, he carefully dug into the Serpent Mound and two nearby cone-shaped mounds. He wanted to learn about the burials inside. After his work, Putnam helped rebuild the mounds to look like they did long ago.

One of the cone-shaped mounds Putnam dug into in 1890 held important items from an Adena burial. He also found nine other burials in the mound. North of this mound, he discovered a bed of ash with many ancient artifacts. After the dig, this cone-shaped mound was rebuilt. It now stands north of the parking lot at the Serpent Mound State Memorial.

In 2011, archaeologists dug again before new utility lines were installed. They focused on three sides of the cone-shaped mound Putnam had explored. They found many ancient artifacts in an ashy soil layer north of the mound.

This ash deposit, which contained wood charcoal, is thought to be from a Fort Ancient Culture ash bed. Carbon dating showed the charcoal was from between 1041 CE and 1211 CE. This means burials in the cone-shaped mound were from both the Early Woodland (Adena) and Fort Ancient periods. This suggests the area was used for rituals over a very long time.

Learning More at the Serpent Mound Museum

In 1901, the Ohio Historical Society hired an engineer named Clinton Cowan. He made a large map of the Serpent Mound and nearby features like hills and rivers. Cowan also studied the area's unique geology. He found that the mound sits where three different types of soil meet.

Cowan's information, along with Putnam's discoveries, has been very important. It forms the basis for all modern studies of the Serpent Mound.

In 1967, the Ohio Historical Society opened The Serpent Mound Museum. It was built very close to the mound itself. A path was made around the mound to guide visitors.

The museum has exhibits that explain the mound's snake shape. It also describes how it was built and the area's geological history. There's also an exhibit about the Adena culture, who were once believed to be the builders.

In 2002, a digital map of the Serpent Mound was created by Timothy A. Price and Nichole I. Stump.

See also

In Spanish: Serpent Mound para niños

In Spanish: Serpent Mound para niños

- Cahokia

- Crooks Mound

- Glades culture

- Hopewell Culture National Historical Park

- Indian Mounds Park

- Mound Builders

- Nazca Lines

- Spiro Mounds

- Marree Man

- List of impact craters on Earth

- List of impact craters in North America

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |