Siege of Aachen (1614) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Aachen |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of War of the Jülich Succession | |||||||

The siege of Aachen by the Spanish Army of Flanders under Ambrogio Spinola in 1614. Oil on canvas. Attributed to Peter Snayers. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| George von Pulitz | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 600 regulars | 15,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None | None | ||||||

The Siege of Aachen happened in late August 1614. During this time, the Spanish Army of Flanders, led by Ambrogio Spinola, marched into Germany. Their goal was to support Wolfgang Wilhelm, Count Palatine of Neuburg, in a conflict called the War of the Jülich Succession.

Aachen was a special city known as a free imperial city, meaning it was mostly independent. However, it was under the protection of John Sigismund of Brandenburg. He was a rival to Wolfgang Wilhelm in a fight over who would rule the United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg.

In 1611, the Protestant people of Aachen rebelled against the city's Catholic leaders and took control. The Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II ordered them to give power back to the Catholics. But the Protestants teamed up with the Margraviate of Brandenburg instead. When the Spanish army suddenly arrived, the Protestants lost hope and surrendered Aachen to Spinola. A Catholic army was then placed in the city, and efforts began to bring back Catholic traditions.

Contents

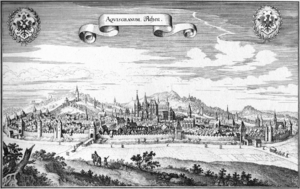

What Was Aachen Like Before the Siege?

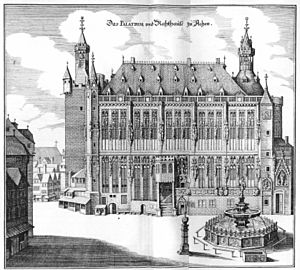

Aachen was a very important free imperial city for a long time, especially during the rule of Charlemagne. It was where German kings were crowned until 1562. After that, Aachen slowly became less important.

Religious Changes in Aachen

At first, Aachen was mostly Catholic. But in the 1560s, many Protestant refugees came from the Netherlands. They were escaping Spanish persecution during the Dutch revolt. By the 1570s, Aachen had about 12,000 Catholics and 8,000 Protestants.

The city leaders and the Emperor tried to stop Protestants from having a say in the government in 1581. However, many Protestants were wealthy and had a lot of economic power. This forced the Catholic leaders to let them join the city council.

The Emperor's Orders and Catholic Rule

The Duke of Jülich and the Bishop of Liege, both Catholic leaders, also claimed control over Aachen. The Catholic people of Aachen asked the Duke of Jülich for help. He then complained to Emperor Rudolf II, saying his religious rights in Aachen were being ignored.

In 1593, a high court called the Reichshofrat decided that the city council could not change Aachen's religious status. This meant the Calvinists (a type of Protestant) had to be removed from the council. When they resisted, Emperor Rudolf declared the city "outlawed." He gave Archduke Albert, who governed the Spanish Netherlands, the job of making sure his decision was followed. The Archbishop of Cologne then helped bring Catholic rule back to the city.

Protestant Rebellion in 1611

In 1611, during the War of the Jülich Succession, Protestant leaders held religious services in nearby villages. In response, Aachen's city council fined anyone who attended these services. Five citizens were arrested for ignoring this rule and were banished when they refused to pay the fine.

This led to a riot against the council on July 5. Catholic leaders were forced out, and many Catholic buildings were attacked. Rebels broke into a church and a Jesuit college, destroying altars and images. They even held a fake mass while dressed in priestly clothes. One priest was hurt, and eight others were dragged to the city council. A new Protestant council was formed, and they asked for help from John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg.

Why Did Spain Get Involved?

Emperor Rudolf II ordered the Protestant leaders to restore the old religious and political situation in Aachen. He threatened them with a ban if they didn't. But the Protestants ignored his command and even hurt an Imperial official sent to enforce the Emperor's order. In May 1612, new elections were held, and Calvinists took control of the town council.

In 1613, the fight over the Jülich succession continued. One of the people claiming the land, Wolfgang Wilhelm, Count Palatine of Neuburg, became Catholic. This gained him the support of Spain and the Catholic League of Germany. On February 20, 1614, Emperor Matthias ordered that Catholic rule be brought back to Aachen. This allowed the Spanish Army of Flanders, led by Ambrogio Spinola, to step in.

Fearing an attack, the town council asked the Elector of Brandenburg for help. He sent several hundred soldiers under General Georg von Pulitz to strengthen the local fighters. The city gates were guarded and partly blocked off.

Spanish and Dutch Preparations

The Spanish plans to get involved in the succession dispute worried the Dutch leader Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange. He supported John Sigismund of Brandenburg and knew that Spanish involvement would make the situation unstable. In mid-June, William Louis, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg, warned Prince Maurice that the Spanish already had 9,800 soldiers ready. He also said that another 13,200 men would join them soon.

With the Spanish threat growing, Maurice sent more soldiers to Jülich and prepared for a possible siege. The situation was tense for both sides. Maurice expected to gather an army of 20,000 men. Meanwhile, Ambrogio Spinola was ready to start his campaign. His first move was towards Aachen.

Spinola explained his reasons for attacking Aachen:

Before we think of the Affairs of Juliers, the vicinity of Aachen ought to engage us to make on that side the first efforts of our army to punish the heretics of that city, and to execute the Imperial Mandate discerned against them, of which the Archduke and the Elector of Cologne are Bearers. Every one knows with what boldness and with what contempt for the Imperial Mandates, the heretic citizens have dar'd usurp the government of Aachen, which belong'd formerly to the Catholics only. Thus an infinity of reasons oblige us to repress by force so unjust an usurpation.

—Ambrogio Spinola to his army, Maastricht, 1614

The Spanish Arrival at Aachen

In August 1614, Spinola moved his army to Maastricht. He had 18,000 foot soldiers, 2,500 cavalry (soldiers on horseback), and 11 cannons. From Maastricht, Spinola's army entered the Rhineland. They were joined by a papal representative and two Imperial officials.

Luis de Velasco, the cavalry general, led the way with 600 horsemen. Behind them came four groups of foot soldiers: one Spanish, one German and Burgundian, and two Walloon. Another 600 horsemen followed at the end. To stop the Dutch from Jülich from helping Aachen, Spinola sent some of his cavalry to block the road between the two cities.

Two hours after leaving Maastricht, the Spanish army appeared outside Aachen. The city did not have strong, modern defenses. It was surrounded by only one old medieval wall. The Spanish troops took control of the hills overlooking the city, close enough to shoot at the walls. They set up cannons to threaten the people and the 600 Brandenburg soldiers inside. After several days of talks, and with little hope of help, the defenders surrendered the city to the Spanish army. Maurice of Nassau was very disappointed because he could not arrive in time to help.

What Happened After the Siege?

The 600 Brandenburg soldiers were allowed to leave Aachen with their flags. They were replaced by 1,200 Catholic Germans led by the Count of Emden. The Spanish soldiers had expected to loot the city, as they had been inactive for years due to a truce with the Dutch Republic. However, Spinola stopped any looting, and Spanish troops did not enter the town.

The Catholic city council was put back in charge. On September 10, they issued an order. Protestant preachers had three days to leave the town. Non-citizen Anabaptists and other foreigners had six weeks to do the same. From then on, only Catholic schools and teachers were allowed. Books considered "heretical" were banned. Eating meat in inns on fast days was not allowed. People also had to show proper respect to the Holy Sacrament and relics during public parades.

Those who took part in the 1611 rebellion were punished. In 1616, two main leaders were executed. More than a hundred citizens who were involved in the unrest were sent away from the city. Others were forced to pay a fine.

Impact on the Jülich Succession War

After taking Aachen, Spinola captured several towns and castles in the lands that were being fought over. These included Neuss, Mülheim, and the important German fortress-city of Wesel. Wesel was guarded by troops from Brandenburg. This weakened the Protestant position in the Rhineland. Spinola decided not to attack Jülich because it had strong defenses and many soldiers.

Maurice of Nassau then marched on Rees with about 18,000 men. Spinola then set up his army near Xanten. There, Spinola and Maurice began talks about a peace agreement. This led to the Treaty of Xanten, which ended the War of the Jülich Succession. It also stopped all fighting between Wolfgang Wilhelm, Count Palatine of Neuburg, and John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg, until 1621.

The lands of Jülich-Berg and Ravenstein went to Wolfgang Wilhelm of Neuburg. The lands of Cleves-Mark and Ravensberg went to John Sigismund. Spinola refused to give up the important fortress of Wesel, so more talks were needed. But in the end, a fragile peace was kept.

See also

In Spanish: Asedio de Aquisgrán (1614) para niños

In Spanish: Asedio de Aquisgrán (1614) para niños

- League of Evangelical Union

- Thirty Years' War

- Catholic League

- Army of Flanders

- Brandenburg-Prussia

- United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |