Siege of Calais (1940) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Calais (1940) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Battle of France | |||||||

The Battle of France, situation 21 May – 4 June 1940 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| c. 4,000 men 40 tanks |

1 panzer division | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| POW: 3,500 British 16,000 French, Belgian and Dutch |

|||||||

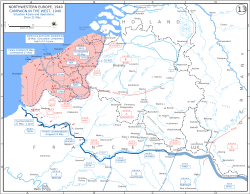

The Siege of Calais (1940) was an important battle for the port city of Calais in France during World War II. It happened at the same time as the Battle of Boulogne. This siege took place just before Operation Dynamo, which was the famous evacuation of British and French soldiers from Dunkirk.

After a counter-attack by French and British forces at the Battle of Arras on May 21, 1940, German units paused. This pause was meant to prepare for another possible counter-attack. General Heinz Guderian, a German commander, wanted to quickly move north to capture the Channel ports like Boulogne, Calais, and Dunkirk. However, his attack was not approved until late on May 21.

By the time the German 10th Panzer Division was ready to attack Calais, British and French troops had strengthened the port's defenses. On May 22, British soldiers set up roadblocks outside the town. French rearguards fought small battles with German armored units as they moved towards Calais. British tanks and infantry were ordered to help Boulogne but arrived too late. They then tried to escort a food convoy to Dunkirk but found the road blocked by German troops.

On May 23, the British began to pull back to the old walls of Calais. The siege officially started on May 24. The German attacks were very costly and often failed. By evening, the Germans reported that about half of their tanks were destroyed and a third of their infantry were wounded or killed. The German attacks were supported by the Luftwaffe (German air force). The Allied defenders received supplies from their navies, who also evacuated wounded soldiers and attacked German targets around the port.

During the night of May 24/25, the defenders had to retreat from the southern outer walls to a shorter line covering the Old Town and the Citadel. Attacks the next day against this new line were pushed back. The Germans tried several times to get the defenders to surrender. However, orders from London told the soldiers to hold out. This was because the French commander of the northern ports had forbidden an evacuation. More German attacks early on May 26 also failed. The German commander was given an ultimatum: if Calais was not captured by 2:00 p.m., the attackers would be pulled back, and the town would be destroyed by the Luftwaffe.

The Anglo-French defenses started to collapse in the early afternoon. At 4:00 p.m., the order "every man for himself" was given to the defenders as the French commander, Le Tellier, surrendered. The next day, small naval ships entered the harbor and picked up about 400 men. Aircraft from the RAF and Fleet Air Arm dropped supplies and attacked German artillery positions.

After the war, in 1949, Winston Churchill wrote that the defense of Calais delayed the German attack on Dunkirk. He believed this helped save 300,000 soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). However, General Guderian disagreed with this in 1951. In 1966, British historian Lionel Ellis wrote that the defense of Boulogne and Calais diverted three German panzer divisions. This gave the Allies time to send troops to close a gap west of Dunkirk. In 2006, Karl-Heinz Frieser suggested that the German halt order on May 21 had a greater effect than the siege itself. He believed Hitler and other German commanders panicked about flank attacks. The real danger was the Allies retreating to the coast before they could be cut off. British reinforcements sent to Boulogne and Calais arrived in time to stop the Germans and hold them off when they advanced again on May 22.

Contents

Why Calais Was Important

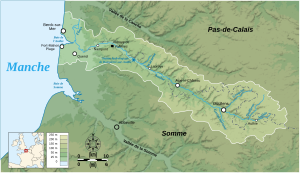

The "Channel Ports" usually refer to Calais, Boulogne, and Dunkirk. These ports are the closest to England and were very popular for passenger travel. Calais is built on low ground with sand dunes nearby. It is surrounded by old fortifications.

Calais' Defenses

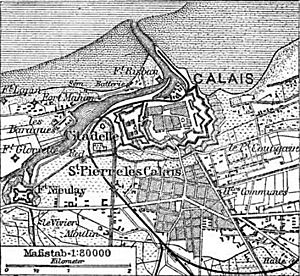

The city had a citadel in the old town, surrounded by water. In 1940, part of the moat was still wet, but other parts were dry. Around the town was an enceinte, which is a defensive wall. This wall was built by Vauban between 1667 and 1707. It had twelve strong points (bastions) connected by a wall, stretching about 8 miles (13 km).

Many parts of the enceinte were overlooked by buildings built in the 1800s. Some of the southern bastions and walls had been removed to make way for railway lines. These lines led to train tracks and docks in the harbor. About 1 mile (1.6 km) west of the enceinte was Fort Nieulay. Other forts to the south and east were old or had disappeared. Outside the town, the low ground to the east and south was cut by ditches. This limited how much land access there was, forcing approaches to be on raised roads. To the west and southwest, there was higher ground between Calais and Boulogne, which overlooked Calais.

British Army's Plans

When the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) made their plans, they learned from the First World War. In that war, the BEF used the Channel Ports for supplies. If the German attack in 1918 had captured these ports, the BEF would have been in a very bad situation.

During the "Phoney War" (September 1939 – May 1940), the BEF got supplies through ports further west, like Le Havre and Cherbourg. But the Channel Ports became important again after mines were laid in the English Channel in late 1939. This helped reduce the need for many ships and escorts. When soldiers started getting leave in December, Calais was used for communication and troop movements.

The German Invasion of France

On May 10, 1940, the Germans launched their attack, called Fall Gelb, against France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Within a few days, a German army group broke through the French lines near Sedan. They quickly moved west, led by tank groups. On May 20, the Germans captured Abbeville, cutting off Allied troops in Northern France and Belgium.

The Battle of Arras, a Franco-British counter-attack on May 21, made the Germans continue attacking north towards the Channel ports. They did not advance south across the Somme River. Fear of another counter-attack led to a "halt order" for German commanders on May 21. Nearby German units were held back, and a division was moved east, even though it was only about 30 miles (50 km) from Dunkirk.

Getting Ready for Battle

German Army Prepares

Late on May 21, the German high command (OKH) canceled the halt order. The German tank group was told to continue its advance about 50 miles (80 km) north to capture Boulogne and Calais. The next day, General Guderian ordered the 2nd Panzer Division to advance to Boulogne. The 1st Panzer Division was to protect its flank, moving towards Calais. This division reached the area of Calais late in the afternoon.

The 10th Panzer Division was kept back to guard against a possible counter-attack from the south. Parts of the 1st and 2nd Panzer Divisions also stayed behind to defend river crossings on the Somme.

Allied Forces Prepare

Calais had been bombed by the Luftwaffe several times. This caused chaos, traffic jams, and confusion, as refugees fled the port. French army units in Calais were commanded by Major Raymond Le Tellier. French naval reservists and volunteers, led by Captain Charles de Lambertye, manned the northernmost defenses. Various scattered army units, including infantry and a machine-gun company, also arrived in the town.

On May 19, Lieutenant-General Douglas Brownrigg of the BEF appointed Colonel Rupert Holland to command British troops in Calais. Holland was also to arrange the evacuation of non-fighting personnel and wounded. The British forces included a platoon of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders guarding a radar site, and several anti-aircraft and searchlight regiments.

When the Germans captured Abbeville on May 20, the British War Office sent troops to the Channel Ports as a precaution. The 20th Guards Brigade went to Boulogne. The 3rd Royal Tank Regiment (3rd RTR), the 1st Battalion Queen Victoria's Rifles (QVR), the 229th Anti-Tank Battery, and the new 30th Motor Brigade were ordered to Calais. Many of these units were not fully ready for battle.

The 3rd RTR was part of the 1st Heavy Armoured Brigade. Their tanks were already loaded on a ship in Southampton, heading for Cherbourg. However, their orders changed, and they were diverted to Dover and then Calais. The QVR was a motorcycle battalion. They were ordered to Dover, leaving their motorcycles and other vehicles behind. This was a mistake, as there was room for their vehicles on another ship, but they sailed without them.

The ships carrying the 3rd RTR and QVR personnel arrived at Calais around 1:00 p.m. The QVR landed without motorcycles, transport, or mortars, and many men only had revolvers. They had to find rifles left behind by others on the quay. While waiting for their vehicles, the 3rd RTR men were bombed in the sand dunes.

The 3rd RTR tanks arrived later at 4:00 p.m., but unloading was very slow. A power cut stopped the cranes, and a strike by the ship's crew caused more delays. The captain even tried to leave without unloading all the tanks until he was stopped at gunpoint. It took until the next morning to unload and refuel the vehicles. The tanks' guns also had to be cleaned and reattached, causing more delays.

The 30th Motor Brigade was formed in April 1940. Its main units were the 1st Battalion, the Rifle Brigade (1st RB), and the 2nd Battalion, King's Royal Rifle Corps (2nd KRRC). Both were well-trained units, each with about 750 men. They were ordered to Southampton on May 21 and sailed on May 23. They arrived in Calais on the afternoon of May 23 and also had to wait for their vehicles to be unloaded.

The Battle Begins

May 22: First Clashes

The 3rd RTR had gathered its 21 light tanks and 27 cruiser tanks near Calais. A patrol of light tanks was sent towards St. Omer. They found the town empty and under bombardment. The patrol returned around 8:00 a.m. on May 23.

RAF aircraft from Britain provided air support. Hawker Hurricanes and Spitfires shot down several German bombers and fighters. German air units also suffered losses during these days.

The German advance continued in the morning. French rearguards, along with some British and Belgian troops, were met at various points. Allied air forces attacked German forces with little opposition from the Luftwaffe. The 10th Panzer Division was then ordered to move to Calais. The 1st Panzer Division, already near Calais, was told to turn east towards Dunkirk. The 10th Panzer Division's advance was delayed, and the British reinforcements in Calais arrived before the Germans.

May 23: Germans Close In

On May 23, the German flanks were secure, and more German air support became available for the 10th Panzer Division at Calais. German dive-bombers (Stukas) were used, but Calais was at the edge of their range. RAF fighters engaged German fighters, with both sides losing aircraft.

A British patrol from the 3rd RTR ran into the advanced guard of the 1st Panzer Division. After some fighting, the British tanks were ordered back to Calais. Other units of the 1st Panzer Division, moving towards Dunkirk, met British troops who had set up a roadblock. These British soldiers held out for about three hours before being overwhelmed. As night fell, the 1st Panzer Division reported that Calais was strongly defended and stopped its attacks to continue towards Dunkirk.

Around 4:00 p.m., the German 10th Panzer Division began its main attack. They advanced towards the high ground near Calais, which offered good views of the city. Another German group was to advance directly into the center of Calais.

When Brigadier Nicholson arrived in Calais with the 30th Infantry Brigade, he found that the 3rd RTR had already suffered losses. The Germans were closing in and had cut off routes to the south. Nicholson ordered the 1st RB to hold the eastern outer walls of Calais and the 2nd KRRC to defend the western side. British outposts outside the town began to retreat to the main defensive wall.

Just after 4:00 p.m., Nicholson received orders from the War Office to escort a convoy of food trucks to Dunkirk. He moved some troops to guard the Dunkirk road, but the 10th Panzer Division arrived and began to shell Calais.

Later that night, a 3rd RTR patrol tried to scout the convoy route. They ran into German roadblocks. The tanks managed to get through some barriers but found many Germans. They eventually reached the British garrison at Gravelines, but their radio failed. A larger force with tanks and infantry tried to lead the convoy at 4:00 a.m. near Marck, east of Calais. They encountered another German roadblock and had to withdraw back to Calais.

May 24: The Siege Begins in Earnest

At 4:45 a.m., French coastal guns opened fire. German artillery and mortar fire then pounded the port, especially French gun positions. This was in preparation for an attack by the 10th Panzer Division on the west and southwest parts of the perimeter. The British troops from the outlying roadblocks completed their withdrawal to the main defensive wall by 8:30 a.m.

The first German attacks were pushed back, except in the south. Here, the Germans broke through but were forced back by a quick counter-attack by the 2nd KRRC and 3rd RTR tanks. The German shelling extended to the harbor, where a hospital train full of wounded waited to be evacuated. The wounded were put on ships, which also carried dock workers and rear-area troops back to England, some with equipment still on board.

In the afternoon, the Germans attacked again on all three sides of the perimeter, with infantry and tanks. The French garrison of Fort Nieulay surrendered after heavy shelling. French marines in other forts destroyed their guns and retreated. On the southern perimeter, the Germans broke in again and could not be pushed back. The defense was made harder by snipers in the town. German troops who broke in fired along the British lines from captured houses. Defenders on the walls ran low on ammunition. By 4:00 a.m., the Germans had only made a small advance. At 7:00 p.m., the 10th Panzer Division reported that a third of their equipment, vehicles, and men were casualties, along with half of their tanks.

The Royal Navy continued to deliver supplies and evacuate wounded. Destroyers like HMS Grafton and HMS Greyhound shelled German targets on shore. German Stuka dive-bombers made a huge effort that day. HMS Wessex was sunk, and a Polish destroyer was damaged by Stukas. British Spitfires attacked the Stukas, shooting down some.

The captain of HMS Wolfhound reported to the Admiralty that the Germans were in the southern part of town and the situation was desperate. Nicholson had received a message from the War Office at 3:00 a.m. that Calais was to be evacuated. However, at 6:00 p.m., he was told that fighting troops would have to wait until May 25. Lacking reserves, Nicholson ordered a retreat to a new defensive line. During the night, the defenders pulled back to the Old Town and the area to the east, inside the outer walls and canals.

French engineers were supposed to prepare the canal bridges for demolition, but this did not happen. The British had no explosives to do it themselves. Nicholson was informed by a signal that the French commander of the Channel Ports had forbidden an evacuation. Nicholson was told to choose the best position to continue fighting. He was also told that a British division was advancing to relieve the defenders. From 10:30 p.m. to 11:30 p.m., French naval gunners disabled most of their guns and went to the docks to embark on French ships. About fifty French volunteers stayed behind to defend Bastion 11.

May 25: Fighting in the Old Town

During the night, Vice-Admiral James Somerville met Nicholson, who said he could hold on longer with more guns. They agreed that the ships in the port should return. At dawn on May 25, the German shelling resumed, focusing on the old town. Buildings collapsed, fires spread, and smoke blocked visibility. The last British anti-tank guns were destroyed, and only three British tanks remained. Distributing food and ammunition was difficult, and broken water pipes meant old wells were the only water source.

At 9:00 a.m., the German commander, Schaal, sent the mayor to ask Nicholson to surrender, but he refused. At noon, Schaal offered another chance to surrender, extending the deadline, but was refused again. The German bombardment increased throughout the day, despite Allied ships trying to shell German gun positions.

In the east, the 1st Rifle Brigade and parts of the QVR on the outer walls and canals pushed back a strong German attack. The French intercepted a German radio message, revealing an attack on the west side, held by the 2nd KRRC. At 1:00 p.m., Nicholson ordered a counter-attack. Eleven Bren carriers and two tanks were to move around to the south to get behind the Germans. The attack failed as the carriers got stuck in the sand. Around 3:30 p.m., the units holding the Canal de Marck were overwhelmed. The 1st RB commander was fatally wounded. The battalion then fought its way northwards through the streets.

In the southeast, a rearguard was surrounded. Only about 30 men out of 150 escaped. Units retreating from the northern part of the walls got a break when German artillery mistakenly shelled their own troops. In the afternoon, a German officer demanded surrender under a flag of truce, but Nicholson refused again. The German attack continued until the commander decided they could not win before dark.

In the old town, the KRRC and QVR fought to defend the three bridges leading into the Old Town from the south. At 6:00 p.m., German artillery stopped, and tanks attacked the bridges. Three German tanks attacked one bridge, and two were destroyed. At another bridge, a tank drove over a mine, and the attack failed. At the third bridge, near the Citadel, the Germans succeeded and captured it. They took cover in houses until counter-attacked by the 2nd KRRC. French and British troops held a bastion, and the French in the Citadel lost many men pushing back attacks. Nicholson set up a joint headquarters with the French.

The commander of the 3rd RTR decided his few remaining tanks could no longer help. He ordered them to withdraw eastwards through the sand dunes. He tried to evacuate 100 wounded men, but they were captured. His last tanks broke down or ran out of fuel and were destroyed by their crews. Some of the crews walked to Gavelines and were later evacuated to Dover.

The RAF continued to provide air cover. They claimed several German Stukas and other aircraft destroyed. German Stukas attacked shipping near the port. The RAF lost some aircraft but also shot down many German planes.

May 26: The Final Stand

Fifteen small naval vessels waited offshore, ready to evacuate men if allowed. Some sailed into Calais harbor without an evacuation order, and one delivered another order for Nicholson to continue fighting. At 8:00 a.m., Nicholson reported to England that his men were exhausted, the last tanks were destroyed, water was scarce, and the Germans were in the north end of town. The strong resistance of the Calais garrison made the German staff consider postponing the final attack. However, the German commander preferred to attack rather than give the British time to send more reinforcements.

At 5:00 a.m., the German artillery resumed its bombardment. More artillery units had been brought from Boulogne, doubling the number of guns available. From 8:30 a.m. to 9:00 a.m., the old town and citadel were attacked by artillery and up to 100 Stukas. After this, German infantry attacked. The 2nd KRRC continued to resist German infantry attacks at the canal bridges. The German commander was told that if the port was not surrendered by 2:00 p.m., the division would be pulled back, and the Luftwaffe would level the town.

The Germans began to break through around 1:30 p.m. Bastion 11 was captured after the French volunteers ran out of ammunition. On the other side of the harbor, the 1st RB held positions around the train station, under attack from the south and east. At 2:30 p.m., the Germans finally overran the train station and another bastion. The survivors of the 1st RB made a last stand before being overwhelmed at 3:30 p.m.

The 2nd KRRC retreated from the three bridges between the old and new towns to a new line. Troops in the Citadel began to show white flags. German tanks crossed one bridge, and British troops scattered, having no weapons to fight tanks. At 4:00 p.m., the new line collapsed, and the 2nd KRRC was given the order "every man for himself." Only one company continued to fight as a unit. The occupants of the Citadel found themselves surrounded around 3:00 p.m. A French officer arrived with news that the French commander, Le Tellier, had surrendered.

During the day, the RAF flew 200 sorties near Calais, losing six fighters. They attacked German Stuka dive-bombers and other aircraft. Fleet Air Arm aircraft bombed German artillery positions. Three British Lysander aircraft were shot down. German fighters protected their Stukas and engaged British aircraft.

After the Battle

Who Was Lost?

In 1952, General Guderian wrote that the British surrendered at 4:45 p.m. and that 20,000 prisoners were taken. This included 3,000–4,000 British troops, with the rest being French, Belgian, and Dutch soldiers. Brigadier Nicholson, the British commander, died in captivity on June 26, 1943. Lieutenant-Colonel Chandos Hoskyns, commanding the Rifle Brigade, was fatally wounded on May 25 and died in England. Captain Charles de Lambertye, the French commander, died of a heart attack on May 26. German reports recorded 160 aircraft lost or damaged from May 22 to 26. The RAF lost 112 aircraft.

What Happened Next?

When the evacuation of troops was stopped, Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay sent smaller boats to remove extra men. One yacht entered the harbor on May 26 and picked up 165 men. During the night of May 26/27, a motor yacht painted with red crosses entered Calais harbor to rescue wounded soldiers. It was fired upon but managed to pick up some British troops and escape.

On May 27, the RAF dropped supplies to the Calais garrison. Twelve Westland Lysander aircraft dropped water at dawn. At 10:00 a.m., 17 Lysanders dropped ammunition on the Citadel, while nine Fairey Swordfish aircraft bombed German artillery positions. Three Lysanders were shot down.

Remembering the Battle

The battle honor Calais 1940 was given to the British units that fought in the siege.

Military Units Involved

Here are some of the main military units that fought in the Siege of Calais.

German Forces

- Panzer Group Kleist (General Ewald von Kleist)

- XIX Korps (General Heinz Guderian)

- 1st Panzer Division

- 2nd Panzer Division

- 10th Panzer Division

- XLI Korps

- 6th Panzer Division

- 8th Panzer Division

Calais Defenders

- 30th Motor Brigade (Brigadier C. N. Nicholson)

- 1st Battalion, Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort's Own)

- 2nd Battalion, King's Royal Rifle Corps

- 7th Battalion, King's Royal Rifle Corps (1st Battalion, Queen Victoria's Rifles)

- 3rd Royal Tank Regiment (under command)

- 229th Anti-Tank Battery, 58th Anti-Tank Regiment, RA (under command)

- 6th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery, 2nd Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, RA (under command)

- 172nd Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, 58th (Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders) Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, RA (under command)

- 1st and 2nd Searchlight Batteries, 1st Searchlight Regiment, RA (under command)

- Elements, 2nd Searchlight Regiment, RA

Images for kids

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |