Sinclair C5 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sinclair C5 |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Overview | |

| Manufacturer | Sinclair Vehicles |

| Production | 1985 |

| Assembly | Merthyr Tydfil, Wales |

| Body and chassis | |

| Class | Battery electric vehicle |

| Layout | Tricycle |

| Powertrain | |

| Electric motor | 250 W (0.34 hp) |

| Battery | 12 V lead–acid battery |

| Range | 20 miles (32 km) |

| Dimensions | |

| Wheelbase | 1,304 mm (51.3 in) |

| Length | 1,744 mm (68.7 in) |

| Width | 744 mm (29.3 in) |

| Height | 795 mm (31.3 in) |

| Kerb weight | 30 kg (66 lb) without battery, approx. 45 kg (99 lb) with battery |

The Sinclair C5 was a small, one-person electric vehicle. It was like a tricycle you could pedal, but it also had a battery-powered motor to help you move. Sir Clive Sinclair, a famous inventor, created it in 1985. He was known for making successful home computers like the ZX Spectrum.

Many people called the C5 an "electric car," but Sinclair himself said it was more of a "vehicle." He wanted to create a new type of electric transport. The C5 was designed with a plastic body and a special frame made by Lotus Cars. It was meant to be the first of many electric vehicles from Sinclair, but later models like the C10 and C15 were never built.

The C5 was launched in January 1985 with a big event. However, it didn't get good reviews from the media. People worried about its safety and how useful it would be. The C5 had a short battery range and a top speed of only 15 miles per hour (24 km/h). It also didn't protect you from the weather. These issues made it hard for most people to use.

It was supposed to be an alternative to both cars and bicycles. But it didn't really appeal to either group. Sales were very low, and production stopped just a few months later in August 1985. Only 5,000 of the 14,000 C5s made were sold. Sinclair Vehicles, the company that made it, soon went out of business.

Even though it wasn't a success at first, the C5 later became a popular item for collectors. Many unsold C5s were bought cheaply and then sold for much higher prices, sometimes up to £6,000! Fans have even created clubs and modified their C5s. Some have added bigger wheels, jet engines, or powerful electric motors to make them go super fast, even up to 150 miles per hour (240 km/h)!

What is the Sinclair C5 like?

The C5 is mostly made of a strong plastic called polypropylene. It is about 174.4 cm (68.7 in) long, 74.4 cm (29.3 in) wide, and 79.5 cm (31.3 in) high. It weighs around 30 kg (66 lb) without its battery and 45 kg (99 lb) with it. The frame is made of a single Y-shaped steel part. The C5 has three wheels: one smaller wheel at the front and two larger ones at the back.

The driver sits in a laid-back position in an open seat. You steer with handlebars located under your knees. There are controls for power and brakes on the handlebars. You can also pedal the C5 like a bicycle to help the motor or if the battery runs out. The fastest an original C5 can go is 15 miles per hour (24 km/h).

At the back, there's a small storage space for your things. It can hold about 28 litres. The C5 doesn't have a reverse gear. So, if you need to turn around, you have to get out, lift the front, and turn it by hand!

How does the C5 get power?

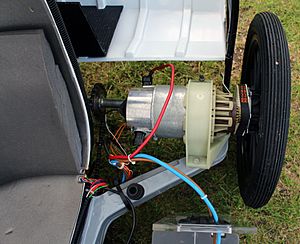

The C5 uses a 12-volt lead–acid battery to power its motor. This motor has a power rating of 250 watts. It also has a special gear system that helps it move the vehicle, especially when starting. If the motor works too hard, like going up a steep hill, it can get hot. The C5 has electronics that watch the motor's temperature. If it gets too hot, the motor will turn off to prevent damage.

Even though it's an electric vehicle, the C5 needs you to pedal sometimes. The battery is designed to last for about 20 miles (32 km) on a full charge. A display inside shows how much battery power is left using green, amber, and red lights. When the last light comes on, you only have about ten minutes of power left. After that, you have to rely on your pedals. Another display shows how much power the motor is using. Green lights mean it's running efficiently, while red lights mean the motor is working hard, and you should pedal to help.

The C5 originally cost £399. To keep the price low, some parts were sold separately. These included turn signals, mirrors, a horn, and a "High-Vis Mast." This mast was a reflective pole to make the C5 easier to see in traffic. Sinclair also sold waterproof clothes for drivers, as the C5's cockpit was open to the weather.

The C5's Story

How the C5 idea started

Sir Clive Sinclair had been interested in electric vehicles since the 1950s. In the 1970s, he ran a successful electronics company. He asked an employee, Chris Curry, to research electric vehicle designs. Sinclair believed that an electric vehicle should be designed from scratch, not just by adding electric parts to a regular car. They even made a small motor for a child's scooter. But other projects, like his famous pocket calculators, became more important.

Early designs: The C1 project

Sinclair returned to electric vehicles in 1979. He hired Tony Wood Rogers to look into making a small, one-person electric vehicle. This project was called the C1. The goal was to create a vehicle for short trips, like a moped, but safer and more weatherproof. It would be easy to drive and park, and cheap to buy (under £500).

Sinclair decided to use existing lead-acid batteries, similar to those in milk floats. He thought that if electric vehicles became popular, battery makers would then create better ones. The C1 design was tested in a wind tunnel to make it aerodynamic. Sinclair then worked with a design company called Ogle Design. However, Ogle's ideas made the C1 too heavy and expensive. By 1983, the C1 project was stopped.

To pay for the vehicle's development, Sinclair sold some of his shares in his computer company. This money helped create a new company called Sinclair Vehicles. Barrie Wills, who had worked for the DeLorean car company, became its managing director.

A new law in Britain helped the C5 project. The government created a new category for "electrically assisted pedal cycles." These vehicles didn't need insurance, vehicle tax, a driving license, or a helmet. This was great for Sinclair, but it also meant the vehicle had limits. It couldn't go faster than 15 miles per hour (24 km/h), weigh more than 60 kilograms (130 lb), or have a motor stronger than 250 watts.

Sinclair saw this as a chance to prove that electric personal transport could work. He hoped the C5 would be as popular as his affordable home computers. However, he didn't do much market research to see if people actually wanted such a vehicle.

Making the C5 design

Ogle Design then worked on a three-wheeled design called the C5. The idea for the handlebars under the knees came from Tony Wood Rogers. He thought a steering wheel would make it hard to get in and out. Later, Lotus Cars helped with the final details and testing. The C5 was developed in secret for 19 months.

An industrial designer named Gus Desbarats was hired to improve the C5's look. He was surprised when he first saw it, expecting a "proper" electric car. He felt the design needed many changes for practicality and safety. But it was too late for big changes. Desbarats focused on making it look better and adding things like wheel covers and a small storage area. He also designed the "High-Vis Mast" because he felt unsafe being so low to the ground.

The C5's frame was made from two metal parts joined together. It didn't have a separate suspension system. The motor came from Italy, and Lotus provided the gearbox and rear axle. The body was made from two large plastic shells. Sinclair had big plans for how many C5s they could make.

The job of assembling the C5 was given to The Hoover Company in Wales. Hoover's factory was in an area that needed jobs, and they were excited by Sinclair's sales predictions. Hoover trained its workers and set up special production lines. By January 1985, over 2,500 C5s had been made.

The C5's big launch

News of the C5 project surprised many people. Some thought Sinclair was "bonkers" for trying to make an electric car. The C5 was officially launched on January 10, 1985, at Alexandra Palace in London. It was a fancy event with lots of promotional items. Six C5s, driven by women, burst out of boxes and drove around. Sinclair announced a big advertising campaign. The C5 would first be sold by mail order for £399, then in stores.

Sinclair's sales brochure said the C5 would put "personal, private transport back where it belongs – in the hands of the individual." It showed people using the C5 for everyday tasks.

However, the launch event for the press was a disaster. Many of the C5s didn't work. Journalists found batteries dying quickly or the vehicle struggling on small hills. Even famous racing driver Stirling Moss had his C5 battery die on a hill! The launch happened in the middle of winter, on a snowy hill, which was not ideal for an open-top vehicle.

What people thought of the C5

Reviews of the C5 were mostly negative. A big concern was that it was too small and low to be safe in traffic. One reporter said your head was only as high as a truck's tires. Drivers worried they wouldn't be seen by larger vehicles. The C5 was also very quiet, making it harder for other drivers to notice.

Some people worried that teenagers, who were a target audience, might drive them dangerously. Sinclair disagreed, saying he worried more about seven-year-olds on bicycles. Teenagers interviewed by The Guardian liked driving it but felt unsafe and preferred their bikes.

Many reviewers called the C5 a "toy" rather than serious transport. They said it was fun but not practical for everyday use in all weather. On the positive side, people praised how easy the C5 was to steer and handle. The Daily Mirror said it was "surprisingly easy" to learn.

Motoring groups and safety organizations were very negative. The British Safety Council said it was dangerous for 14-year-olds to drive without a license or training. Sinclair was very angry and threatened to sue, but nothing came of it.

Sales and problems

Despite the bad press, Sinclair hoped for good sales from the public launch event. But fewer than 200 C5s were sold at the event. However, sales picked up from mail orders, and 5,000 C5s were sold within four weeks.

Some famous people bought C5s, including Princes William and Harry for use at Kensington Palace, and musician Sir Elton John. But many early buyers were disappointed by its limited range and inability to climb steep hills. Some returned their C5s for a refund.

Sales dropped when the C5 reached stores in March 1985. Sinclair even hired teenagers to drive C5s around London to promote them. He blamed the press for the low demand. Production had to stop for three weeks because of a problem with a plastic part in the gearbox. When production restarted, it was at only 10% of the original level. Thousands of unsold C5s piled up.

Sinclair tried to sell the C5 in other countries, but most wanted changes to its brakes and more reflectors. Consumer groups also published critical reports. The Automobile Association found the C5's real range was only about 10 miles (16 km), not the promised 20 miles (32 km). They also questioned its safety. Which? magazine reported that all three C5s they tested broke down. They also said it was "too easy to steal" because it was so light.

By July, only 8,000 C5s had been sold. The Advertising Standards Authority told Sinclair to change or remove its ads because claims about safety and speed couldn't be proven. Stores started cutting the price drastically. Comet sold C5s for as low as £139.99, much less than the original price.

Production ended in August 1985. Sinclair Vehicles had financial problems and owed Hoover money. The company went out of business in October 1985.

Why the C5 failed

Many reasons have been suggested for the C5's failure. One of the company's receivers thought it was marketed incorrectly. He believed it should have been sold as a "luxury product, an up-market plaything" instead of serious transport. When another company bought the remaining C5s, they marketed them as "a sophisticated toy" and sold nearly 7,000 of them at a higher price than Sinclair ever did!

Some experts said Sinclair's marketing was confusing. The ads showed it as a fun leisure vehicle, but the text said it was a serious car alternative. It tried to appeal to two different groups but didn't truly connect with either. Also, selling it only by mail order at first meant people couldn't see it before buying, which was a risk.

The C5's designer, Gus Desbarats, felt Sinclair didn't understand the difference between a new market like computers and an old one like transport. He said Sinclair was in a "bubble." Sinclair himself later said the C5 was "early for what it was." He also agreed that people felt insecure because it was so low to the ground.

Today, experts say the C5 was ahead of its time. The roads and attitudes of the 1980s weren't ready for small electric vehicles. But now, with more cycle lanes and a focus on green transport, the world is much more open to alternatives to cars.

What came after the C5?

Sinclair's other electric vehicle ideas

Sinclair had plans for more electric vehicles after the C5. These included the C10, a two-seater city car, and the C15, a three-seater that could go up to 80 miles per hour (130 km/h). The C10 was meant to be a city car for two people, with a roof but open sides. It looked a lot like the modern Renault Twizy electric car.

The C15 was planned to be a futuristic, tear-drop shaped car. It would use new types of batteries that could give it much more speed and a range of over 180 miles (290 km). However, these new batteries didn't work out, so neither the C10 nor the C15 were ever built.

The C5's failure hurt the reputation of electric vehicles in the UK for a long time. The media often compared new electric cars to the C5. It wasn't until the 1990s, when Toyota launched the successful Prius, that the "C5 jinx" was finally broken.

In 2017, Sir Clive's nephew, Grant Sinclair, introduced an updated version of the C5 called the Iris eTrike.

From failure to fan favorite

Even though the C5 wasn't a commercial success, it became a cult item. Collectors started buying them as investments. One investor bought 600 C5s and sold them for much more than their original price. He found buyers who wanted a unique or eco-friendly way to get around. He also sold them to people who had lost their driving licenses, as the C5 didn't need one. By 1996, a special edition C5 in its original box could be worth over £5,000!

C5 owners began changing their vehicles to make them perform much better than Sinclair ever imagined. One owner, Adam Harper, even modified a C5 to go 150 miles per hour (240 km/h)! He aimed to break a world record for a three-wheeled electric vehicle.

In 1985, two people, John W. Owen and Roy Harvey, drove a Sinclair C5 from John O'Groats to Land's End, a distance of 919 miles (1,479 km). It took them 103 hours and 15 minutes!

Other engineers have done amazing things with C5s. Chris Crosskey drove one 103 miles (166 km) to Glastonbury and tried to drive one across Britain three times. Adrian Bennett even put a jet engine on his C5! Another inventor, Colin Furze, turned one into a 5-foot-high (1.5 m) "monster trike" with huge wheels and a petrol engine that could go 40 miles per hour (64 km/h).

Musician John Otway often uses a C5 in his stage shows.

See also

- eROCKIT

- List of motorized trikes

- Velomobile

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |