Clive Sinclair facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Clive Sinclair

|

|

|---|---|

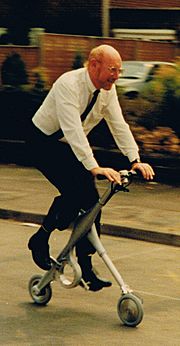

Sinclair in Bristol, 1992

|

|

| Born |

Clive Marles Sinclair

30 July 1940 Ealing, England

|

| Died | 16 September 2021 (aged 81) London, England

|

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1961−2010 |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Ann Trevor-Briscoe

(m. 1962; div. 1985)Angie Bowness

(m. 2010; div. 2017) |

| Children | 3 |

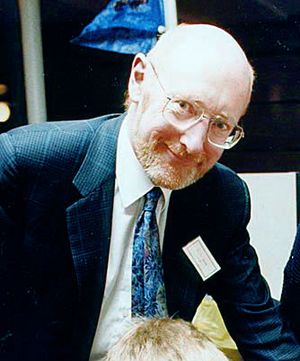

Sir Clive Marles Sinclair (born 30 July 1940 – died 16 September 2021) was an English inventor and business owner. He is famous for being a leader in the computer industry. He also started several companies that made consumer electronics in the 1970s and early 1980s.

Sinclair founded Sinclair Radionics Ltd in 1961. In 1972, he created the world's first thin pocket calculator, called the Sinclair Executive. Later, in 1980, he started making home computers with Sinclair Research Ltd. His company produced the ZX80, which was the UK's first affordable home computer costing less than £100. In the early 1980s, he also released the ZX81, ZX Spectrum, and the Sinclair QL. Sinclair Research was very important in the early days of the British and European home computer industry. It also helped start the British video game industry.

Sir Clive Sinclair also had some products that were not successful. These included the Black Watch wristwatch and the Sinclair Vehicles C5 battery electric vehicle. The C5's failure and a weaker computer market led Sinclair to sell most of his companies by 1986. After that, he focused on personal transport, like the A-bike. This was a folding bicycle small enough to fit in a handbag. He was made a Knight Bachelor in 1983 for his work in the personal computer industry in the UK.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Clive Sinclair's father and grandfather were both engineers. His grandfather, George Sinclair, was a naval architect. He helped make the paravane, a device used to clear mines from the sea. Clive's father, George William "Bill" Sinclair, became a mechanical engineer.

Clive Sinclair was born in 1940 in Ealing, which is now part of west London. During World War II, he and his mother moved to Devon for safety. Their home in Ealing was bombed. His family later settled in Bracknell. Clive had a brother, Iain, born in 1943, and a sister, Fiona, born in 1947.

Sinclair went to Boxgrove Preparatory School where he was very good at mathematics. He did not enjoy sports and felt out of place at school. Because his father had financial problems, Clive had to change schools several times. He finished his O-levels at Highgate School in London in 1955. He then studied physics and maths at St. George's College, Weybridge.

From a young age, Sinclair showed an interest in electronics. He earned money by mowing lawns and working in a café. He also took holiday jobs at electronics companies. While still at school, he wrote his first article for Practical Wireless magazine. After leaving school at 18, he started selling small electronic kits by mail order to people who enjoyed hobbies.

Career Highlights

Starting Sinclair Radionics

Clive Sinclair's ideas for electronics began early. In 1958, he designed a radio circuit and planned how to sell it. He also wrote several books for Bernard's Publishing about building electronic circuits. His first book, Practical transistor receivers Book 1, came out in 1959.

In 1961, Sinclair officially started his first company, Sinclair Radionics Ltd. He wanted to raise money to advertise his inventions and buy parts. He designed PCB kits and licensed some of his technology. He tried to find someone to help produce his miniature transistor pocket radio as a kit.

Since he couldn't find enough money, Sinclair worked as a technical editor for Instrument Practice magazine. This job gave him access to many electronic devices. He bought rejected semiconductor parts from a company called Semiconductors Ltd. He fixed these parts and sold them under his own brand.

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, Sinclair Radionics was making handheld electronic calculators, small televisions, and the digital Black Watch wristwatch. The Black Watch, released in 1975, was not very successful. It had problems meeting customer demand, was often inaccurate, hard to fix, and its battery didn't last long.

Sinclair Radionics lost money in 1975–1976. Sinclair looked for investors to help. He worked with the National Enterprise Board (NEB), which bought a part of his company in 1976. However, this help came too late. Other companies were already making similar products at lower prices. The NEB decided to sell off parts of Sinclair Radionics. Sinclair himself left the company in 1979.

Creating Sinclair Research

While dealing with problems at Radionics, Sinclair had a former employee, Christopher Curry, start a new company called Science of Cambridge Ltd in 1977. One of its first products was a wrist calculator kit.

When Sinclair joined Science of Cambridge, affordable microprocessors were becoming available. Sinclair had the idea to sell a kit to teach people about microprocessors. In 1978, Science of Cambridge launched the MK14 kit. Around this time, Christopher Curry left to start Acorn Computers, which became a competitor.

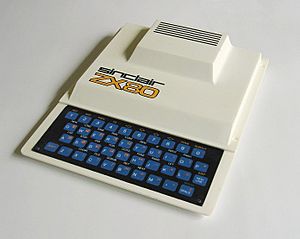

Sinclair then wanted to build a personal computer. In 1979, most computers cost about £700. Sinclair believed he could make one for under £100. Keeping costs low was important to compete with American and Japanese products. In May 1979, Jim Westwood, a former Sinclair Radionics employee, started the ZX80 project. It was launched in February 1980, costing £79.95 as a kit or £99.95 ready-built. The ZX80 was an instant success. Science of Cambridge was renamed Sinclair Research Ltd.

Sinclair also developed the Sinclair ZX81, which launched at an even lower price. Even though the BBC chose Acorn's computer for a TV series, Sinclair's computers became very popular. The ZX80 and ZX81 were among the best-selling computers in the UK and the United States. Many user groups, magazines, and accessories appeared for these computers.

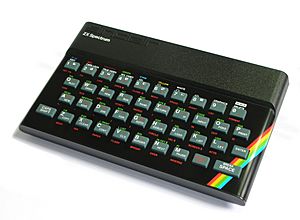

In 1982, Timex got a license to sell Sinclair's computers in the United States as Timex Sinclair. In April, the ZX Spectrum was launched. It cost £125 for the 16 kB version and £175 for the 48 kB version. This was the first ZX computer with colour. The ZX Spectrum was more affordable than other computers like the BBC Micro or Apple II.

During a time of economic difficulty in the UK, Sinclair promoted the Spectrum as a low-cost home computer. It also became a popular gift for teenagers. Many young people learned to program on the ZX Spectrum. They used its new colour features to create unique video games. These "bedroom coders" helped start the UK's video game industry. By 1984, over 3,500 games were available for the ZX Spectrum.

The ZX Spectrum became very popular in Western Europe. Even in Eastern European countries, many low-cost copies of the ZX Spectrum appeared. This further boosted video game development there. The ZX Spectrum became the UK's best-selling computer, selling over 5 million units before it stopped being made in 1992. By 1984, Sinclair Research computers made up 45% of the British market.

The success of the computer market helped Sinclair Research make a lot of money. In 1982, the company made £9.2 million in profit. Sinclair himself was estimated to be worth over £100 million in 1983. With this money, Sinclair moved his company headquarters to a former mineral water factory in 1982.

Sinclair Vehicles and Market Changes

As Sinclair Research continued to do well, Sinclair started a new company, Sinclair Vehicles Ltd., in March 1983. This company was made to develop electric vehicles. Sinclair had been interested in electric vehicles since the 1970s. The company's only product was the Sinclair C5, launched in January 1985.

The Sinclair C5 was not successful. It was developed without checking what people wanted. Many people criticized it for its high price, its toy-like look, lack of safety features, and the need to pedal it up hills. Sinclair hoped to sell 100,000 C5s in the first year. However, only 14,000 were made and 4,500 sold before production stopped in August 1985.

Another product that didn't do well was the Sinclair Research TV80. This was a flat-screen portable mini television. By the time it was ready in 1983, other companies like Sony had already released similar products. Also, newer LCD screen technology was being developed. The TV80 was a commercial failure, with only 15,000 units made. Despite their failures, both the C5 and TV80 are now sometimes seen as ideas that were ahead of their time. The C5 is like an early version of today's electric cars, and the TV80 is similar to watching videos on smartphones.

Sinclair continued to lead Sinclair Research, releasing more ZX Spectrum computers in 1983 and 1984. He also launched the Sinclair QL (short for Quantum Leap) in 1984. This computer was meant to compete with business computers from IBM and Apple, but at half the cost. However, by late 1984, the computer market in the UK became difficult. Sinclair Research and Acorn Computers had a price war. These price drops made consumers see computers more as toys than tools.

The lack of money for Sinclair Research and the failure of the C5 caused financial problems for Sinclair. Sinclair Vehicles went out of business by October 1985. In April 1986, Sinclair sold most of Sinclair Research to Amstrad for £5 million. Sinclair Research Ltd. then became a smaller company focused on research and development. It also held shares in other companies that used technologies developed by Sinclair.

Later Years and Inventions

By 1990, Sinclair Research was much smaller, with only Sinclair and two other employees. At its busiest in 1985, it had 130 employees. Later, the company focused on personal transport, like the Sinclair Zike electric bicycle. By 2003, Sinclair Research worked with a Hong Kong company called Daka. They worked together on products like a Sea Scooter and a wheelchair drive. In 1997, he invented the Sinclair XI, a very small radio.

Sinclair also planned to release the Sinclair X-1 through Sinclair Research. This was another attempt at a personal electric vehicle after the C5. The X-1 was announced in 2010. It tried to fix the problems of the C5. It had an open, egg-like shape for the rider, a more comfortable seat, a stronger motor, and a bigger battery. It was also designed to be more affordable than the C5. However, the X-1 never made it to the market.

Recognition and Awards

Sir Clive Sinclair received several awards for his important work in starting the personal computer industry in the United Kingdom. In 1983, he was given special degrees from the University of Bath, Heriot-Watt University, and University of Warwick. He was made a knight by the Queen in 1983. In 1984, Imperial College London made him a fellow. In 1988, the National Portrait Gallery in London bought a portrait of Sinclair for its collection.

Personal Life

Clive Sinclair enjoyed playing poker and appeared on a TV show called Late Night Poker. He won the first final of a spin-off show called Celebrity Poker Club. Sinclair was an atheist. He had a very high IQ of 159 and was the chairman of British Mensa from 1980 to 1997. He also ran in several marathons, including the New York City Marathon.

Even though he was involved in computing, Sinclair did not use the Internet himself. He said he didn't like to have "technical or mechanical things around me" because they distracted him from inventing. In 2010, he said he didn't use computers and preferred using the telephone over email. In 2014, he predicted that if machines become as smart as or smarter than humans, it would be difficult for humans to survive.

His first marriage to Ann lasted twenty years and ended in divorce around 1985. He had three children with Ann: Crispin, Bartholomew, and Belinda. In 2010, Sinclair married Angie Bowness. This second marriage lasted seven years and also ended in divorce.

Sir Clive Sinclair died in London on 16 September 2021, at the age of 81. He had been ill with cancer for over ten years. After his death, many people, including Elon Musk and Satya Nadella, remembered him for his important contributions to computing and video games. An article in The Times newspaper described Sinclair as a determined inventor. His career showed how perseverance, even through failures, can lead to success, much like other great British inventors.

See also

In Spanish: Clive Sinclair para niños]

In Spanish: Clive Sinclair para niños]