Siphonophorae facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siphonophorae |

|

|---|---|

|

|

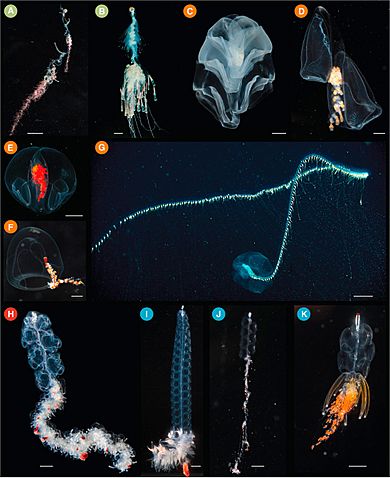

| (A) Rhizophysa eysenhardtii scale bar = 1 cm, (B) Bathyphysa conifera 2 cm, (C) Hippopodius hippopus 5 mm, (D) Kephyes hiulcus 2 mm (E) Desmophyes haematogaster 5 mm (F) Sphaeronectes christiansonae 2 mm, (G) Praya dubia 4 cm (1.6 in), (H) Apolemia sp. 1 cm, (I) Lychnagalma utricularia 1 cm, (J) Nanomia sp. 1 cm, (K) Physophora hydrostatica 5 mm | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Class: | Hydrozoa |

| Subclass: | Hydroidolina |

| Order: | Siphonophorae Eschscholtz, 1829 |

| Suborders | |

|

|

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Siphonophores (say: sy-FON-oh-fores) are amazing sea creatures. They belong to a group called Hydrozoa, which are part of the larger Cnidaria family. This family also includes jellyfish and corals.

Even though a siphonophore might look like one animal, it's actually a team! It's a colony made up of many tiny parts called zooids. Each zooid has a special job, like helping the colony move, eat, or make babies.

These zooids work together to form a single, working colony. They can float, digest food, and even move using a kind of jet propulsion. Most siphonophores are long, thin, and clear, floating in the open ocean.

Like some other sea animals, siphonophores can make their own light. This is called bioluminescence. They use this light to attract food or to scare away predators. One special type of siphonophore, Erenna, is one of the few creatures known to make red light!

Contents

What are Siphonophores?

Colony Life

Siphonophores are colonial animals, meaning they live as a group of connected parts. These parts, called zooids, grow from a single starting cell. All zooids in a colony are usually identical copies, like clones.

Each zooid has a specific job. Some help with eating, some with moving, and some with reproduction. This teamwork makes the whole colony strong and able to survive. The zooids are usually attached to a long central stem.

Body Shapes

Siphonophores come in three main body plans, which are like different designs:

- Cystonects have a long stem with zooids attached. They have a gas-filled float called a pneumatophore at one end. This helps them float near the water's surface.

- Physonects also have a pneumatophore. They have special swimming bells called nectophores that help them move by jet propulsion.

- Calycophorans are different because they don't have a float. Instead, they have two nectophores that help them swim.

Special Zooids and Their Jobs

Each zooid in a siphonophore colony has a unique role:

- Nectophores: These are like swimming engines. They help the siphonophore move through the water by pushing water backward.

- Bracts: These zooids are special to siphonophores. They help protect the colony and keep it floating at the right depth.

- Gastrozooids: These are the feeding zooids. They have tentacles to catch and digest food.

- Palpons: These are modified feeding zooids that help control the flow of fluids inside the colony.

- Gonophores: These zooids are in charge of reproduction, making eggs or sperm.

- Pneumatophores: These are gas-filled floats found in some siphonophores. They help the colony stay upright and float in the water.

Where Siphonophores Live

There are about 175 known species of siphonophores. They live in all the world's oceans, mostly in the deep sea. They can be found at different depths, depending on their size and shape.

Smaller siphonophores that live in warmer, shallower waters often eat tiny animals like zooplankton. Larger siphonophores live in deeper, calmer waters and eat bigger prey. They are usually found floating freely in the open ocean.

How Siphonophores Behave

Movement

Siphonophores move using a method similar to jet propulsion. Their many swimming zooids, called nectophores, work together. The smaller nectophores at the top help with turning and steering. The larger ones at the bottom provide the main thrust for speed.

This teamwork allows the whole colony to move efficiently. If some nectophores get damaged, others can take over, so the colony can keep moving. This is a great advantage for survival!

Hunting and Eating

Siphonophores are carnivores, meaning they eat other animals. Their diet includes small crustaceans and fish. They often use a "sit-and-wait" strategy, letting their long tentacles spread out to catch unsuspecting prey.

Many siphonophores have stinging cells called nematocysts on their tentacles. When prey touches a tentacle, these cells shoot out tiny, paralyzing toxins. The tentacles then wrap around the prey, bringing it to the feeding zooids for digestion.

Some siphonophores are very clever hunters. The Erenna siphonophore can make its tentacles twitch and glow with red light. This mimics small creatures, luring prey closer so the siphonophore can catch them.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Siphonophores reproduce in different ways, and scientists are still learning about some of them. Generally, a single fertilized egg grows into a tiny starting zooid. This zooid then buds off new zooids, creating the whole colony around a central stalk.

Siphonophores have special zooids called gonophores that produce either eggs or sperm. Some colonies have both male and female gonophores (called monoecious), while others have separate male and female colonies (called dioecious).

Bioluminescence: Making Light

Almost all siphonophores can make their own light, which is called bioluminescence. This glowing ability is often used for defense, like a warning signal to predators.

However, some deep-sea siphonophores, like those in the Erenna group, also use light to hunt. They create a flickering red light with their tentacles. This light looks like small prey animals, tricking fish into coming closer. Even though red light doesn't travel far in the deep ocean, some deep-sea fish might still be able to see it.

Other siphonophores use their light to mimic different creatures. For example, Agalma okeni might mimic fish larvae, while Lychnafalma utricularia might look like a small jellyfish. This helps them attract their specific prey.

Siphonophore Discoveries

The first siphonophore, the famous Portuguese man o' war, was described in 1758 by Carl Linnaeus. For a long time, scientists only found a few new species.

In the 1800s, many more species were discovered during big ocean exploration trips. A scientist named Ernst Haeckel drew many beautiful pictures of siphonophores, which are still useful today.

In the 20th century, A. K. Totton became a very important siphonophore researcher, discovering many new species.

More recently, in 2020, scientists found a giant Apolemia siphonophore near Australia. It was incredibly long, possibly the largest siphonophore ever seen!

Even though siphonophores have been around for a very long time (their relatives date back 640 million years!), we don't have any fossil records of them. This is because their bodies are very soft and don't leave fossils easily.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Siphonophora para niños

In Spanish: Siphonophora para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |