Stephen Toulmin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

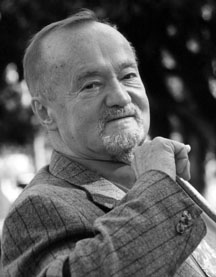

Stephen Edelston Toulmin

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 25 March 1922 London, England

|

| Died | 4 December 2009 (aged 87) Los Angeles, California, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | King's College, Cambridge |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Analytic |

|

Main interests

|

Meta-philosophy, argumentation, ethics, rhetoric, modernity |

|

Notable ideas

|

Toulmin model (Toulmin method) Good reasons approach |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Stephen Edelston Toulmin (born March 25, 1922 – died December 4, 2009) was a British thinker, writer, and teacher. He was inspired by another philosopher, Ludwig Wittgenstein. Toulmin spent his career studying how people make moral decisions. He wanted to find ways to build strong, practical arguments. These arguments could help people think about what is right and wrong.

Later, his ideas became very useful in the field of rhetoric. Rhetoric is the art of speaking or writing effectively. His most famous idea is the Toulmin model of argumentation. This model is a diagram with six parts. It helps people understand and analyze arguments. He first shared this model in his 1958 book, The Uses of Argument. It became very important in communication and even in computer science.

Contents

About Stephen Toulmin

Stephen Toulmin was born in London, UK, on March 25, 1922. His parents were Geoffrey and Doris Toulmin. He went to King's College, Cambridge and earned his first degree in 1943. After that, he worked for the Ministry of Aircraft Production during World War II. He was a junior scientific officer.

After the war, he went back to Cambridge University. He earned his Master's degree in 1947 and his PhD in philosophy. His PhD paper was later published as a book. While at Cambridge, he met the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein's ideas about how we use language greatly influenced Toulmin's own work.

From 1949 to 1954, Toulmin taught Philosophy of Science at Oxford University. During this time, he wrote another book. It was called The Philosophy of Science: an Introduction. He then taught in Australia for a year. After that, he became a professor at the University of Leeds in England.

While at Leeds, he published his very important book, The Uses of Argument (1958). This book looked at the weaknesses of traditional logic. At first, other philosophers in England didn't like it much. They even joked about it. But in the United States, people who studied rhetoric loved it. They saw that his ideas could help analyze arguments.

In 1960, Toulmin returned to London. He became the director of a group that studied the History of Ideas. In 1965, he moved back to the United States. He taught at many different universities there. He also helped publish books by his friend N.R. Hanson after Hanson passed away.

At the University of California, Santa Cruz, Toulmin wrote Human Understanding (1972). This book explored how our ideas and concepts change over time. He compared this change to Charles Darwin's idea of biological evolution. He suggested that our understanding of things also evolves.

In 1973, he worked with Allan Janik on the book Wittgenstein's Vienna. This book argued that truth can depend on history and culture. It was different from older ideas that said truth is always the same.

From 1975 to 1978, Toulmin worked with a US government commission. This group protected people in medical and behavior research. He also wrote a book called The Abuse of Casuistry: A History of Moral Reasoning (1988). This book showed how to solve moral problems using specific examples.

One of his later books was Cosmopolis: The Hidden Agenda of Modernity (1990). In this book, he criticized how modern science sometimes ignores moral issues.

Toulmin taught as a distinguished professor at many top universities. These included Columbia University, Dartmouth College, and the University of Chicago.

In 1997, he received the Jefferson Lecture award. This is a very high honor for people in the humanities in the U.S. His lecture talked about how modern ideas developed. He warned against being too rigid in our thinking. He said we need to combine technical and humanistic ideas.

On March 2, 2006, Toulmin received an award from Austria for his work in science and art.

He was married four times. He had four children: Greg, Polly, Camilla, and Matthew.

Stephen Toulmin passed away on December 4, 2009, in Los Angeles, California. He was 87 years old.

Toulmin's Ideas on Philosophy

Thinking About Absolutes and Relatives

In his work, Toulmin often said that "absolutism" isn't very useful in real life. Absolutism means believing in universal truths that never change. It suggests that all moral problems can be solved with one set of rules, no matter the situation. But Toulmin argued that many of these rules don't fit real-life problems.

To explain this, Toulmin talked about "argument fields." In The Uses of Argument (1958), he said that some parts of an argument change depending on the field (like law or science). These are "field-dependent." Other parts of an argument are the same in all fields. These are "field-invariant." Toulmin believed that absolutism was wrong because it ignored the "field-dependent" parts. It thought everything was "field-invariant."

He also looked at "relativism." Relativism suggests that truth depends on culture or context. Toulmin felt that relativists focused too much on the "field-dependent" parts and ignored the "field-invariant" parts. Toulmin wanted to find ways to judge ideas that were neither completely absolute nor completely relative.

In Cosmopolis (1990), he explored why philosophers often looked for "certainty." He praised thinkers who moved away from this idea.

Making Modernity More Human

In Cosmopolis, Toulmin explored where our modern focus on universal truths came from. He criticized modern science and philosophy for ignoring practical problems. He felt they focused too much on abstract ideas. For example, he saw a decrease in moral thinking in science. He felt science shifted its focus from environmental issues to creating things like the atomic bomb.

To fix this, Toulmin suggested we return to "humanism." This meant four things:

- Going back to talking and discussing ideas, instead of just reading them.

- Focusing on specific, individual cases of moral problems in daily life.

- Considering the local, or the specific cultural and historical situations.

- Thinking about what is important now, instead of timeless problems.

He continued these ideas in Return to Reason (2001). He discussed how universal ideas have caused problems in society. He also looked at the difference between what ethical theories say and what happens in real life.

How to Build an Argument: The Toulmin Model

Toulmin believed that "absolutism" wasn't practical. So, he wanted to create a different kind of argument, called "practical arguments." Unlike theoretical arguments, practical arguments focus on justifying a claim. They start with an idea and then provide reasons to support it. Toulmin thought that reasoning was more about testing existing ideas than finding new ones. This testing happens through justification.

He believed a good argument needs strong reasons to support its claim. This helps it stand up to criticism. In The Uses of Argument (1958), Toulmin suggested a model with six parts for analyzing arguments:

- Claim (Conclusion): This is the main point you want to prove. In an essay, it's like your thesis statement. For example, if someone wants to prove they are a British citizen, the claim is: "I am a British citizen."

- Ground (Fact, Evidence, Data): These are the facts or evidence that support your claim. For example, the person might say: "I was born in Bermuda."

- Warrant: This is the link that connects your ground to your claim. It's the rule or principle that allows you to move from the evidence to the conclusion. For example: "A person born in Bermuda is legally a British citizen."

- Backing: This is extra support for your warrant. You use backing if your warrant isn't strong enough on its own. For example, if someone doubts the warrant, you might say: "I trained as a lawyer in London, specializing in citizenship, so I know that a person born in Bermuda will legally be a British citizen."

- Rebuttal (Reservation): This part acknowledges situations where your claim might not be true. It shows you've thought about other possibilities. For example: "A person born in Bermuda will legally be a British citizen, unless they have betrayed Britain and become a spy for another country."

- Qualifier: These are words or phrases that show how sure you are about your claim. Words like "probably," "possibly," "certainly," or "presumably" are qualifiers. For example, "I am definitely a British citizen" is stronger than "I am a British citizen, presumably."

The first three parts—claim, ground, and warrant—are essential for practical arguments. The other three—qualifier, backing, and rebuttal—might not be needed in every argument.

Toulmin first created this model for legal arguments, like those used in a courtroom. He didn't realize it could be used in rhetoric until others pointed it out. Later, in his book Introduction to Reasoning (1979), he mentioned how useful it was for communication.

One criticism of the Toulmin model is that it doesn't always focus on the questions behind an argument. It assumes you start with a fact or claim. But it doesn't always look at why certain questions are asked in the first place.

Toulmin's model has inspired many other tools. These include ways to map out arguments and software to help with them.

Ethics and Morality

The "Good Reasons" Approach

In his 1950 book, Reason in Ethics, Toulmin introduced his "Good Reasons approach" to ethics. He criticized other philosophers who he felt didn't fully explain how we reason about right and wrong.

Bringing Back Casuistry

Toulmin wanted to find a middle ground between "absolutism" and "relativism." He did this by bringing back an old method called casuistry. Casuistry (also known as case ethics) was used a lot in the Middle Ages to solve moral problems.

In The Abuse of Casuistry: A History of Moral Reasoning (1988), Toulmin worked with Albert R. Jonsen. They showed how casuistry was effective in the past. This helped bring it back as a useful way to argue.

Casuistry uses general rules, called "type cases" or "paradigm cases." But it doesn't use them in an absolute way. It uses these standard rules (like "the importance of life") as guides. Then, a specific situation is compared to these type cases. If a situation is exactly like a type case, you can make a moral judgment right away. If the situation is different, you look closely at the differences to make a fair decision.

Through casuistry, Toulmin and Jonsen found three tricky situations in moral reasoning:

- When a type case doesn't clearly fit a specific situation.

- When two different type cases seem to apply to the same situation, but they conflict.

- When a completely new situation comes up that doesn't match any existing type case.

Using casuistry, Toulmin showed how important it is to compare situations when making moral arguments. This was something that absolutist or relativist theories didn't focus on.

Science and Evolution of Ideas

The Evolutionary Model of Ideas

In 1972, Toulmin published Human Understanding. In this book, he argued that changes in our ideas happen through an evolutionary process. He disagreed with another philosopher, Thomas Kuhn. Kuhn believed that ideas changed through sudden "revolutions." Kuhn thought that old ideas were completely replaced by new ones.

Toulmin criticized Kuhn's idea of "relativism." He argued that if old and new ideas were completely different, you couldn't compare them. Toulmin felt Kuhn focused too much on the "field variant" parts of arguments. He ignored the common parts shared by all scientific ideas.

Instead of Kuhn's "revolutionary" model, Toulmin suggested an "evolutionary" model. This was similar to Darwin's idea of biological evolution. Toulmin said that changes in ideas involve two steps: innovation and selection. Innovation is when new ideas appear. Selection is when the best ideas survive and continue.

Innovation happens when people in a field start to see things differently. Selection means these new ideas are debated and tested. Toulmin called this a "forum of competitions." The strongest ideas survive this competition. They either replace old ideas or improve them.

From an absolutist view, ideas are either right or wrong, no matter the situation. From a relativist view, one idea is not better than another from a different culture. But Toulmin believed that judging ideas depends on comparing them. You see if one idea explains things better than its rivals.

Works by Stephen Toulmin

- An Examination of the Place of Reason in Ethics (1950)

- The Philosophy of Science: An Introduction (1953)

- The Uses of Argument (1958)

- Foresight and Understanding: An Enquiry into the Aims of Science (1961)

- The Fabric of the Heavens (1961) with June Goodfield

- The Architecture of Matter (1962) with June Goodfield

- The Discovery of Time (1965) with June Goodfield

- Human Understanding: The Collective Use and Evolution of Concepts (1972)

- Wittgenstein's Vienna (1973) with Allan Janik

- Knowing and Acting: An Invitation to Philosophy (1976)

- An Introduction to Reasoning (1979) with Allan Janik and Richard D. Rieke

- The Abuse of Casuistry: A History of Moral Reasoning (1988) with Albert R. Jonsen

- Cosmopolis: The Hidden Agenda of Modernity (1990)

- Return to Reason (2001)

Recognitions

In April 2011, Stephen Toulmin was chosen for the Pantheon of Skeptics by the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI). This group honors people who have made important contributions to scientific skepticism.

See also

In Spanish: Stephen Toulmin para niños Argumentation theory Cambridge University Moral Sciences Club

In Spanish: Stephen Toulmin para niños Argumentation theory Cambridge University Moral Sciences Club

Images for kids

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |