Surrender of General Botho Elster facts for kids

The surrender of Major General Botho Elster was a big event during World War II. On September 17, 1944, General Elster and over 19,000 German soldiers gave up to the United States Army in Beaugency, France.

At this time, France was quickly being freed from Nazi Germany's control by the Allied armies. Elster and his soldiers were trying to escape from France. But their escape route to Germany was blocked by Allied forces. They were also surrounded by French Resistance fighters and attacked by Allied planes. Because of this, Elster decided to talk about surrendering to the U.S. Army.

Some members of the French Resistance were not happy about this surrender. They felt that their important role in making Elster surrender was not recognized.

Contents

Why the Surrender Happened

After the Normandy Invasion in France, General George Patton and the U.S. Third Army moved very quickly in August 1944. Their southern border was the Loire River. To protect the Third Army's side, the 83rd Infantry Division, led by Major General Robert C. Macon, was told to guard the north bank of the Loire River. This area stretched for about 300 kilometers (186 miles).

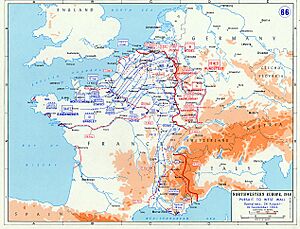

While Allied armies were moving through northern France, the U.S. Army also landed in southern France near Marseilles. This was part of an operation called Operation Dragoon. They quickly moved north. By early September, most of France was controlled by the Allied forces.

In southwestern France, German commander Major General Botho Elster had been very harsh with the French Resistance. By August 23, it was clear that Elster would soon be trapped by the Allies. So, the first groups of his 20,000 men left Mont-de-Marsan. They tried to march across France to escape to Germany.

Elster's group was a mix of soldiers, sailors, police, and others. Many traveled in horse-drawn wagons, on bicycles, or walked. They wanted to escape more than they wanted to fight. They were also afraid of revenge from the Resistance. The shortest way to Germany was through Dijon, but that route was being closed by Allied forces. Elster first headed north, then turned east. To avoid Allied air attacks, his force spread out over many miles of road.

The Resistance, helped by secret Jedburgh teams and British agents, kept bothering Elster's retreating forces. Allied planes also attacked them. The strong French Resistance in the Indre area had about 6,000 fighters. They were supplied with weapons by a British agent named Pearl Witherington.

The 83rd Infantry blocked Elster's way north by holding the north bank of the Loire River. A French army of 30,000 men, called the "Schneider Column," blocked Elster from going east on September 7. On the same day, U.S. and British air forces bombed Elster's men near Châteauroux. This killed 400 Germans and 300 horses and destroyed 70 vehicles. Elster was completely surrounded by the French Resistance.

The French Resistance demanded Elster's surrender on August 29, but the Germans did not reply.

How the Surrender Was Negotiated

Lieutenant Samuel Wallace Magill was 24 years old. He led a special group of 24 American soldiers and volunteers from other countries. This group was called the "Platoon International" because its members spoke 12 different languages. Magill's group was part of the U.S. Army's 329th Infantry Regiment. They were spread out along the north bank of the Loire River. Their job was to guard the side of the U.S. Army.

Even though they were told not to cross the Loire, Magill and a few others crossed the river on September 7. The French Resistance told Magill that a German force wanted to surrender. Magill, along with two French captains and a Scottish agent named Tommy Macpherson, went to Issoudun. They carried a white flag and saw thousands of German soldiers.

In Issoudun, Magill met General Elster. Elster explained his terms for surrendering. He wanted to see at least two American army battalions as a sign of force. This would make his surrender look justified. Elster insisted he would only talk to and surrender to the Americans, not the French Resistance.

Magill went back to his base and told General Macon, the commander of the 83rd Infantry. Macon could not gather enough infantry for a show of force. Instead, he arranged for the U.S. Army Air Force to do a flyover. The next day, September 8, Magill went back to Issoudun to meet Elster again. At 2:47 p.m., sixteen Republic P-47 Thunderbolt planes flew very low over the German army. Magill told Elster he could either surrender or be bombed. Elster chose to negotiate.

The Surrender Ceremony

The idea of 20,000 Germans surrendering got a lot of attention from the news. Journalists went with American officers to Elster's headquarters to record the surrender. On September 10, General Macon went to Issoudun to sign a first surrender agreement. Major Arthur H. Clutton, a British agent, signed for the British and for French Resistance leader Raymond Chomel.

Elster convinced Macon that the Germans would be in danger from the French Resistance if they gave up their weapons. So, Macon agreed that the Germans could keep their weapons while marching 120 kilometers (75 miles) to Beaugency. This march was through Resistance-controlled land. The formal surrender would happen in Beaugency, on the north side of the Loire River, in American-controlled territory. The Germans had been very cruel during their march north, so the danger from the Resistance was real.

The U.S. Army Air Force also took credit for the surrender. They said that for the first time, planes alone had forced a large enemy force to surrender. They did not mention the Resistance's role.

Not everyone agreed with the surrender terms. A Resistance leader named Philippe de Vomécourt worried that a fight would break out between the Germans and the Resistance during the march. He tried to get General Patton to change the agreement. De Vomécourt said the agreement went against the Allied policy of "unconditional surrender." He claimed Patton agreed, but de Vomécourt was hurt in a car accident and could not deliver Patton's order to change the surrender.

The German march from Issoudun to Beaugency through Resistance areas was more like a victory parade than a defeat. The Germans "swaggered" and sang their marching songs as they went through villages. Just a week before, they had murdered people in those same villages. Clutton's team and Sam Magill's group escorted the Germans to Beaugency. They worried the Germans might try to loot the Chateau de Valencay. This castle was hiding famous art from the Louvre museum, like the Winged Victory of Samothrace and the Venus de Milo. Magill's group placed land mines at the castle entrance to make sure no German soldiers went that way.

On September 17, 1944, the formal surrender ceremony happened on the Beaugency bridge over the Loire River. News cameras were there, making it one of the most filmed surrenders. Generals Elster, Macon, and Otto P. Weyland (from the Army Air Force) were present. No one from the French Resistance was invited. Sam Magill was later asked to stand among the colonels and generals. This caused some surprise because he was just a lieutenant. Magill was later invited to Paris to tell his platoon's story to the media.

The French Resistance was left out of the surrender. Their important help in freeing France "was not even recorded."

Elster surrendered 754 officers, 18,850 men, and two women. They also gave up 400 trucks, 1,000 wagons, 2,000 horses, 4,000 automatic weapons, and other military gear.

What Happened Next

Pearl Witherington, the British agent, was very angry about how easily Elster's Germans were treated. She was also upset that the Resistance was left out. She said General Macon did not understand that the Germans surrendered only because of the French Resistance. She also complained that the Americans gave the German soldiers oranges, chocolate, and American cigarettes. These were luxuries that French people did not have during the war. She said her "boys" were "freedom fighters" and that "we [the Resistance fighters] liberated France south of the Loire." On September 21, she was told to return to London.

Arthur Clutton, the British agent, tried to make sure the surrender agreement was followed. The agreement said the French Resistance should get the surrendered German weapons. But Charles de Gaulle, the head of the French government, stopped this. He worried the weapons would go to Resistance groups, especially communists, who were against his government. Clutton also tried to get the captured German vehicles and horses returned to French civilians. He said the horses were dying from neglect. Instead, his mission ended on September 25, and he was ordered to Paris.

Being left out of the surrender and its rewards was very upsetting for the French Resistance. Local French citizens burned American flags and sent angry letters to newspapers.

Sam Magill was considered very important as the leader of his special platoon. He remained a lieutenant until the end of World War II. France gave him a Croix de Guerre medal, and the U.S. gave him a Legion of Merit. He rejoined the army around 1950 as an intelligence officer. He retired as a lieutenant colonel in 1969 and lived in Munich, Germany, until he died in 2013. After retiring from the military, he worked as an advisor for many movies about World War II. Botho Elster was sentenced to death by a Nazi court in 1945 for surrendering without permission. He died of a heart attack in Germany in 1952 and was cleared of the charges in 1998.

See also

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |