Szilárd petition facts for kids

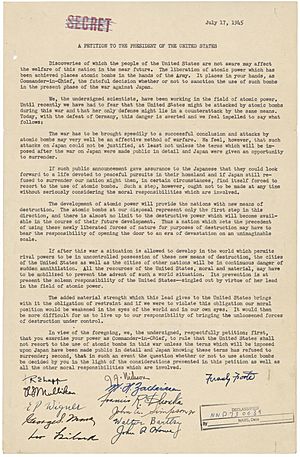

The Szilárd petition was a special letter written in July 1945 by a scientist named Leo Szilard. About 70 other scientists working on the top-secret Manhattan Project signed it. These scientists worked in places like Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Chicago, Illinois. The petition asked President Harry S. Truman to tell Japan the surrender terms before using atomic weapons. It also asked him to let Japan choose to accept or refuse these terms. However, this important letter never reached President Truman. It was kept secret until 1961.

Later, in 1946, Szilard and Albert Einstein started the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists. Famous scientists like Linus Pauling (who won a Nobel Peace Prize in 1962) were part of this group.

Contents

Why the Petition Was Written

Before the Szilárd petition, another report called the Franck Report was written. This report was put together by a group led by James Franck. Szilárd and his colleague Glenn T. Seaborg helped write it. The Franck Report suggested that after the war, countries should share information about atomic energy. This would help prevent a nuclear arms race. It also said that Japan should be warned properly before the atomic bomb was used. This was to keep good feelings towards the United States.

The Szilárd petition was different from the Franck Report. The Franck Report focused on politics and international teamwork. But the Szilárd petition was a strong moral request. The scientists who signed it knew that nuclear weapons could spread quickly. They warned that if the United States used the bomb to end the war in the Pacific, it would "open the door to an era of devastation." This meant they feared a time of unimaginable destruction. They worried that using the bomb would make the U.S. lose its moral standing. This would make it harder to control the nuclear arms race that would follow.

Many of the first signers worked in Chicago on the Manhattan Project. Scientists there had different ideas about what to do with the bomb. So, the lab director, Farrington Daniels, asked 150 scientists for their opinions. Here's what they thought:

- 15% believed the bomb should be used as a weapon. This would force Japan to surrender and save Allied soldiers' lives.

- 46% thought the military should show the bomb in Japan first. They hoped this would lead to surrender. If not, then it should be used as a weapon.

- 26% suggested showing the bomb in the United States as an experiment. A group from Japan would watch. The hope was they would tell their government to surrender.

- 11% said the bomb should only be used in a public demonstration.

- 2% believed the bomb should not be used in war at all. They also thought its secrets should be kept completely hidden.

Szilárd asked his friend, physicist Edward Teller, to help get more signatures. He wanted Teller to share the petition at Los Alamos National Laboratory. But Teller first spoke to the Los Alamos director, J. Robert Oppenheimer. Oppenheimer told Teller that leaders in Washington were already deciding. He said the lab scientists should not get involved. So, no more signatures were gathered at Los Alamos.

What the Petition Said

The petition was sent to President Truman. It explained that the Manhattan Project was first started to protect the U.S. from a possible nuclear attack by Germany. But by then, the threat from Germany was gone. The scientists then strongly asked Truman to make all surrender terms public. They wanted him to wait for Japan's answer before dropping the atomic bomb. They also asked him to think about his "obligation of restraint."

The petition said: "If after this war a situation is allowed to develop in the world which permits rival powers to be in uncontrolled possession of these new means of destruction, the cities of the United States as well as the cities of other nations will be in continuous danger of sudden annihilation... The added material strength which this lead gives to the United States brings with it the obligation of restraint and if we were to violate this obligation our moral position would be weakened in the eyes of the world and in our own eyes. It would then be more difficult for us to live up to our responsibility of bringing the unloosened forces of destruction under control. We, the undersigned, respectfully petition: first, that you exercise your power as Commander-in-Chief, to rule that the United States shall not resort to the use of atomic bombs in this war unless the terms which will be imposed upon Japan have been made public in detail and Japan knowing these terms has refused to surrender; second, that in such an event the question whether or not to use atomic bombs be decided by you in the light of the considerations presented in this petition as well as all the other moral responsibilities which are involved."

In simpler words, the scientists warned that if countries had these powerful new weapons without control, cities everywhere would be in constant danger. They felt that America, having this new power, had a duty to be careful. If the U.S. used the bomb without warning, it would lose its moral standing. This would make it harder to control these dangerous new forces. They asked President Truman to promise not to use the atomic bomb unless Japan knew the surrender terms and still refused to give up. They also asked him to consider all moral duties when deciding whether to use the bombs.

What Happened Next

In the spring of 1945, Szilárd took the petition to James F. Byrnes. Byrnes was soon to become the Secretary of State. Szilárd hoped Byrnes would tell President Truman that scientists believed the bomb should not be used on civilians. He also hoped Byrnes would agree that after the war, atomic weapons should be controlled by all countries. This would help avoid a future arms race. However, Byrnes did not agree with Szilárd's ideas at all. Because of this, President Truman never saw the petition before the bombs were dropped.

Szilárd was sad that Byrnes had so much power. He even felt bad about becoming a physicist because he had helped create the bomb. After meeting Byrnes, Szilárd reportedly said, "How much better off the world might be had I been born in America and become influential in American politics, and had Byrnes been born in Hungary and studied physics." In response to the petition, General Leslie Groves, who led the Manhattan Project, even tried to find reasons to accuse Szilárd of wrongdoing.

The first atomic bomb, called Little Boy, was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Three days later, a second bomb, called Fat Man, was dropped on Nagasaki. These bombs led to an estimated 200,000 civilians dying. Many believe they also led to Japan's surrender. In December 1945, a survey by Fortune magazine found that over three-quarters of Americans approved of using the bombs.

Despite this, a group of very important scientists spoke out against the decision. They also warned about a future nuclear arms race. A book called One World or None: A Report to the Public on the Full Meaning of the Atomic Bomb was released in 1946. It included essays by Leo Szilárd, Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, Robert Oppenheimer, and others. The main message of the book, which sold over a million copies, was that nuclear weapons should never be used again. It also said that countries should work together to control them.

Who Signed the Petition

The 70 scientists who signed the petition worked at the Manhattan Project's Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago. Here they are, listed in alphabetical order with their jobs:

- David S. Anthony, Associate Chemist

- Larned B. Asprey, Junior Chemist, S.E.D.

- Walter Bartky, Assistant Director

- Austin M. Brues, Director, Biology Division

- Mary Burke, Research Assistant

- Albert Cahn, Jr., Junior Physicist

- George R. Carlson, Research Assistant-Physics

- Kenneth Stewart Cole, Principal Bio-Physicist

- Ethaline Hartge Cortelyou, Junior Chemist

- John Crawford, Physicist

- Mary M. Dailey, Research Assistant

- Miriam Posner Finkel, Associate Biologist

- Frank G. Foote, Metallurgist

- Horace Owen France, Associate Biologist

- Mark S. Fred, Research Associate-Chemistry

- Sherman Fried, Chemist

- Francis Lee Friedman, Physicist

- Melvin S. Friedman, Associate Chemist

- Mildred C. Ginsberg, Computer

- Norman Goldstein, Junior Physicist

- Sheffield Gordon, Associate Chemist

- Walter J. Grundhauser, Research Assistant

- Charles W. Hagen, Research Assistant

- David B. Hall, Physicist

- David L. Hill, Associate Physicist, Argonne

- John Perry Howe, Jr., Associate Division Director, Chemistry

- Earl K. Hyde, Associate Chemist

- Jasper B. Jeffries, Junior Physicist, Junior Chemist

- William Karush, Associate Physicist

- Truman P. Kohman, Chemist-Research

- Herbert E. Kubitschek, Junior Physicist

- Alexander Langsdorf, Jr., Research Associate

- Ralph E. Lapp, Assistant To Division Director

- Lawrence B. Magnusson, Junior Chemist

- Robert Joseph Maurer, Physicist

- Norman Frederick Modine, Research Assistant

- George S. Monk, Physicist

- Robert James Moon, Physicist

- Marietta Catherine Moore, Technician

- Robert Sanderson Mulliken, Coordinator of Information

- J. J. Nickson, [Medical Doctor, Biology Division]

- William Penrod Norris, Associate Biochemist

- Paul Radell O'Connor, Junior Chemist

- Leo Arthur Ohlinger, Senior Engineer

- Alfred Pfanstiehl, Junior Physicist

- Robert Leroy Platzman, Chemist

- C. Ladd Prosser, Biologist

- Robert Lamburn Purbrick, Junior Physicist

- Wilfrid Rall, Research Assistant-Physics

- Margaret H. Rand, Research Assistant, Health Section

- William Rubinson, Chemist

- B. Roswell Russell, position not identified

- George Alan Sacher, Associate Biologist

- Francis R. Shonka, Physicist

- Eric L. Simmons, Associate Biologist, Health Group

- John A. Simpson, Jr., Physicist

- Ellis P. Steinberg, Junior Chemist

- D. C. Stewart, S/Sgt S.E.D.

- George Svihla, position not identified [Health Group]

- Marguerite N. Swift, Associate Physiologist, Health Group

- Leo Szilard, Chief Physicist

- Ralph E. Telford, position not identified

- Joseph D. Teresi, Associate Chemist

- Albert Wattenberg, Physicist

- Katharine Way, Research Assistant

- Edgar Francis Westrum, Jr., Chemist

- Eugene Paul Wigner, Physicist

- Ernest J. Wilkins, Jr., Associate Physicist

- Hoylande Young, Senior Chemist

- William Houlder Zachariasen, Consultant