Tanacross language facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Tanacross |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neeʼaanděgʼ | ||||

| Native to | United States | |||

| Region | Alaska (middle Tanana River) | |||

| Ethnicity | 220 Tanana (2007) | |||

| Native speakers | <10 (2020) | |||

| Language family |

Dené–Yeniseian?

|

|||

| Writing system | Latin script | |||

| Official status | ||||

| Official language in | ||||

|

||||

|

||||

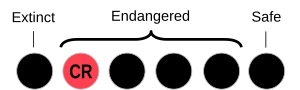

Tanacross (also called Transitional Tanana) is a special language spoken by the Tanana people in eastern Interior Alaska. Sadly, this language is in danger of disappearing, with less than 60 people still speaking it.

Contents

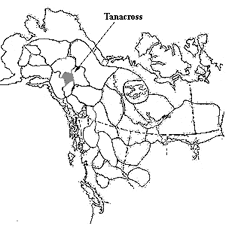

Where Tanacross is Spoken

The name Tanacross refers to both a village in eastern Alaska and the group of people who speak this language. The main village of Tanacross is connected by a road to the Alaska Highway. Some speakers now live in Tok, which is about ten miles east of the village. Others live in Fairbanks, a larger city about 200 miles away.

Tanacross is the original language of the Mansfield-Kechumstuk and Healy Lake-Joseph Village groups of Tanana Athabaskan people. Their traditional land stretched from the Goodpaster River in the west to the Alaska Range in the south. It also went from the Fortymile and Tok rivers in the east to the Yukon Uplands in the north.

In the late 1800s, trading posts were set up at a river crossing called Tanana Crossing. This was a place where people could cross the Tanana River on the Eagle Trail. Later, a telegraph station was built in 1902, and an Episcopal mission opened in 1909. Both the Mansfield-Kechumstuk and Healy Lake-Joseph Village groups eventually settled at Tanana Crossing, which was later shortened to Tanacross. In the early 1970s, the village moved across the river to where it is today. Most Tanacross speakers still live in or near this village.

How the Language Got its Name

The name "Tanacross" for the language is quite new and mostly used by experts. For a long time, people used other names. For example, in 1839, one list called it "Copper River Kolchan."

Later, in the 1960s, a language expert named Michael Krauss started using the term "Transitional Tanana." He saw that it was different from other Tanana languages. As people understood these differences better, the name "Tanacross" was given to this specific language area.

The people who speak Tanacross often just call it "Indian" or "Native Language." They usually don't like the term "Athabaskan." They also have a word, neò/aòneg, which means 'our language'.

Tanacross is part of a larger group of related languages. To the northwest is the Han language, spoken in Eagle, Alaska, and across the border in Canada. To the east is Upper Tanana, spoken in villages like Tetlin and Northway. Tanacross and Upper Tanana are quite similar, and speakers can often understand each other. To the south, near the Copper River, is the Ahtna language. The Mentasta dialect of Ahtna is very similar to Tanacross.

Different Ways of Speaking Tanacross

The area where Tanacross is spoken is not very big, so there aren't many different ways of speaking it. However, there are two main dialects:

- Mansfield-Kechumstuk (MK) Dialect:' This dialect is called Dihthâad Xt'een Aandeg, which means "The Mansfield People's Language." It was spoken by groups from Mansfield Lake and Kechumstuk, who later moved to Tanacross village. This is the dialect most often studied.

- Healy Lake-Joseph Village Dialect: This dialect is spoken by groups at Healy Lake and Dot Lake. It is different because it keeps certain vowel sounds (called schwa suffixes) that the MK dialect does not.

Long ago, Lower Tanana was spoken at Salcha, which is west of the Tanacross area. The Salcha dialect shared some features with the Healy Lake dialect of Tanacross. However, the Salcha dialect is now gone, making the boundary between Tanacross and Lower Tanana even clearer.

Current Status of Tanacross

Like all Athabaskan languages in Alaska, Tanacross is in great danger of disappearing. Most children can understand some simple words and phrases, but most people who speak Tanacross fluently are at least 50 years old. Only the very oldest speakers use Tanacross every day.

In 1997, experts estimated there were about 65 speakers out of a total population of 220. Even though the number of speakers is small, it's a high percentage compared to other Alaska Athabaskan languages. Outside of Tanacross village, the number of speakers is much lower. For example, at Healy Lake and Dot Lake, there are only a few speakers left.

Even though Tanacross village is small (about 140 people) and close to the non-Native community of Tok, it has its own school. Sometimes, Tanacross reading and writing are taught there. Also, most homes in the village have at least one person who speaks Tanacross fluently.

Recently, more people, especially middle-aged adults, have become interested in bringing the language back to life. Workshops have been held to teach the language, and some speakers have even become certified to teach it. There are also plans for Tanacross language classes at the University of Alaska center in Tok.

Sounds of Tanacross

Tanacross is one of only four Athabaskan languages in Alaska that uses tone. This means that the way you say a word (the pitch of your voice) can change its meaning. The other languages with tone are Gwichʼin, Han, and Upper Tanana. Tanacross is special because it uses a high tone where other languages might use a low tone.

Vowel Sounds

Tanacross has six main vowel sounds. These are like the sounds of 'ee' in 'see', 'ay' in 'say', 'ah' in 'father', 'oo' in 'moon', 'uh' in 'sofa', and 'oh' in 'go'.

Some vowels can be long or short. In writing, long vowels are shown by doubling the letter, like 'aa' for a long 'a' sound. Vowels can also have different tones, shown by marks above them, like á for high tone or â for falling tone.

Consonant Sounds

The consonant sounds in Tanacross are written in a special way. Some sounds that are usually written with letters like 't' or 'k' in English might be written with 'd' or 'g' in Tanacross, even if they sound a bit like 't' or 'k'. This is because of how the sounds are made in the mouth.

One unique thing about Tanacross is its "semi-voiced" fricatives. These are sounds that start without voice and then become voiced. They are shown in writing with an underscore, like s or ł.

How Tanacross is Related to Other Languages

Tanacross belongs to the Athabaskan language family. This is a large group of languages found in three different parts of North America:

- The Northern group in northwestern Canada and Alaska (where Tanacross is).

- The Pacific Coast group in northern California, Oregon, and southern Washington.

- The Apachean group in the southwestern United States, which includes Navajo, one of the largest Native American languages.

It's hard to group the Northern Athabaskan languages into smaller families because they are all very similar. The languages along the Tanana River are like a chain, from Lower Tanana in the west to Upper Tanana in the east. Tanacross was only recognized as its own language in the late 1960s.

Tanacross shares many features with its neighbors, like the Mentasta dialect of Ahtna, the former Salcha dialect of Lower Tanana, the Tetlin dialect of Upper Tanana, and the Han language.

However, Tanacross stands out because of its unique high tone system. Other nearby languages like Lower Tanana, Han, and Upper Tanana developed a low tone, while Ahtna either didn't develop tone or lost it. The tone system in Tanacross is very important for how words sound and how they are used.

Tanacross has strong connections with Upper Tanana to the east. These groups have often shared traditions like potlatch ceremonies. This suggests that the Tanana Uplands area, including people from Tetlin, Northway, Beaver Creek, Eagle, Dawson City, and Mentasta, share a common language and culture. Many people in this area speak more than one language, so understanding Tanacross means understanding its place in this larger group of languages.

Early Studies of Tanacross

Many people have helped to study and record the Tanacross language and culture. Books by Isaac (1988) and Simeone (1995) offer important information about the Tanacross community. Isaac's book is an oral history told by Chief Andrew Isaac, the last traditional chief of Tanacross. It talks about plants, animals, and cultural items. Simeone's book is a description of the culture written by someone who lived in Tanacross village in the 1970s.

The very first written record of the Tanacross language was a list of words from 1839. Later, in the 1900s, other short word lists were collected. More serious work began with Michael Krauss in the 1960s and 70s. Nancy McRoy collected texts and a word list, and Jeff Leer made notes on grammar and sounds.

In the early 1990s, John Ritter helped create a practical way to write the Tanacross language. Tanacross speakers Irene Solomon Arnold and Jerry Isaac worked on creating materials to help people learn to read and write the language. They even made cassette tapes to go with the materials.

Since 2000, Irene Solomon has worked as a language specialist at the Alaska Native Language Center. She has worked with linguist Gary Holton on many projects, including a phrase book, a dictionary for learners, and a multimedia guide to the language's sounds.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Idioma tanacross para niños

In Spanish: Idioma tanacross para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |