White-shouldered antshrike facts for kids

Quick facts for kids White-shouldered antshrike |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Male | |

|

|

| Memale | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Thamnophilus

|

| Species: |

aethiops

|

|

|

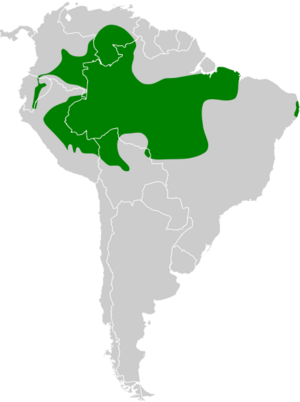

The white-shouldered antshrike (Thamnophilus aethiops) is a type of bird. It belongs to a group of birds called "typical antbirds." You can find this bird in several South American countries, including Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela.

Contents

About the White-shouldered Antshrike

The white-shouldered antshrike was first described by a zoologist named Philip Sclater in 1858. This bird is closely related to the uniform antshrike and the upland antshrike. They are like "sister species," meaning they share a common ancestor not too long ago.

There are 10 different types, or subspecies, of the white-shouldered antshrike. These subspecies often live in different areas, sometimes separated by large rivers in the Amazon Basin. Because of this, some scientists think that these different types might actually be separate species!

- T. a. aethiops Sclater, PL, 1858

- T. a. wetmorei Meyer de Schauensee, 1945

- T. a. polionotus Pelzeln, 1868

- T. a. kapouni Seilern, 1913

- T. a. juruanus Ihering, HFA, 1905

- T. a. injunctus Zimmer, JT, 1933

- T. a. punctuliger Pelzeln, 1868

- T. a. atriceps Todd, 1927

- T. a. incertus Pelzeln, 1868

- T. a. distans Pinto, 1954

Appearance of the Antshrike

The white-shouldered antshrike is about 15 to 17 cm (5.9 to 6.7 in) long. It weighs between 23 to 30 g (0.81 to 1.1 oz), which is about as much as a few quarters. Like other antbirds, it has a strong beak with a hook at the end, similar to a shrike bird.

Male and female white-shouldered antshrikes look quite different. This is called sexual dimorphism.

- Adult males are mostly black. They have some small white spots on their wings.

- Adult females are a deep reddish-brown color all over.

- Younger males look more like adult females, but they also have pale spots on their wings.

The different subspecies of the white-shouldered antshrike have small differences in their colors and markings. For example, some males might have more gray, or different patterns of white spots on their wings or tail feathers. Females of different subspecies can also have slightly different shades of brown or reddish-brown.

Where They Live and Their Home

The white-shouldered antshrike lives in different parts of South America:

- Some live in eastern Ecuador and Peru.

- Others are found in Colombia, Venezuela, and parts of Brazil.

- You can also find them in western Brazil and northern Bolivia.

- One subspecies lives separately in northeastern Brazil, near the coast.

These birds mostly live in evergreen forests. They prefer the thick, dense plants and bushes found close to the ground, called the understorey. In some areas, like Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, they live in the foothills of the Andes mountains. They can be found at different heights, from sea level up to about 1,500 m (4,900 ft) in Peru.

In places like Venezuela and the Amazon region of Brazil, they often live at the edges of forests, especially near rivers. They also like areas where trees have fallen, creating overgrown gaps. In some parts of Brazil, they are often found near stands of Guadua bamboo.

Antshrike Behavior

Movement

White-shouldered antshrikes usually stay in the same area all year round. They don't migrate long distances.

What They Eat

We don't know all the details about what white-shouldered antshrikes eat. But we do know they eat insects and other small bugs, called arthropods. They usually look for food alone or in pairs. They almost always search for food in thick plants and bushes.

These birds don't often join large groups of different bird species looking for food. They usually search for food between 1 and 5 m (3 and 16 ft) off the ground. However, in bamboo areas, they might go as high as 8 m (26 ft). They hop among branches, reaching out or making short jumps to grab prey from leaves, stems, and branches. Sometimes, they even fly down to the ground to find food in fallen leaves. There's even one record of a pair following a group of army ants to catch insects that the ants disturbed!

Reproduction and Life Cycle

The breeding season for the white-shouldered antshrike changes depending on where they live. Breeding activity has been seen in different months like February, July, September, October, and November.

Their nest is shaped like a deep cup. It's made very tightly from grass and thin roots. Sometimes, they cover the outside with green moss and rotting leaves. The nest is usually hung in a branch fork, about 2.5 m (8 ft) off the ground. A female usually lays two eggs. Both the male and female birds take turns sitting on the eggs to keep them warm. They also both feed the baby birds once they hatch. We don't know exactly how long it takes for the eggs to hatch or for the young birds to leave the nest.

How They Communicate

The male white-shouldered antshrike's song is a short series of low, complaining notes. They sing at a steady speed and sound. The female's song is similar but has a higher pitch. People have described their song as "anh...anh...anh...anh...anh," sung about one note per second. It sounds a bit like a barred forest falcon or a trogon.

Their most common call is a quick, throaty "cuck." They often repeat this call for a long time. They also make other sounds like "caws," "nasal twangs," and growls. Scientists are still studying if the songs are different among the various subspecies.

Conservation Status

The IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) has decided that the white-shouldered antshrike is a species of "Least Concern." This means they are not currently in danger of disappearing. They live across a very large area. We don't know the exact number of these birds, but their population is thought to be decreasing. However, no immediate big threats have been found.

The bird is not very common in most places it lives. But it does live in many protected areas, including places set aside for indigenous people. The only exception is the subspecies T. a. distans. This type seems to be in more trouble because much of its forest home in northeastern Brazil has been destroyed. This is happening because of the growing sugar cane industry in that area.