The Fur Trade in Canada facts for kids

The Fur Trade in Canada is a book written in 1930 by Harold Innis. It talks about how the fur trade greatly affected First Nations people. The book also explains how trading furs made European settlers in Canada rely on this business. Most importantly, it shows how the fur trade helped shape Canada's future as a country.

| Top - 0-9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z |

Understanding the Fur Trade: The Beaver's Role

Harold Innis starts his book by talking about the beaver. The fur of the beaver became very popular in Europe. People loved beaver hats, which were waterproof and stylish. Innis believed you couldn't understand the fur trade or Canadian history without knowing about beavers.

He studied how the beaver's life and habits affected the trade. Innis learned that to understand a product, you must study its geography. First Nations cultures were closely tied to the land. Their hunting skills and knowledge of the land shaped the fur trade. For beaver pelts, the best quality came from older animals. The time of year the beaver was hunted also mattered.

Where Beavers Lived and Why It Mattered

The most valuable beaver fur came from north of the St. Lawrence River. This area included the forests of the Pre-Cambrian Shield. It had many waterways, which beavers love. Innis noted that beaver pelts were light, usually less than two pounds. This made them easy to carry long distances. Beavers were also a good source of food.

Beavers do not travel much over land. They also move very slowly. While they have many babies, it takes over two years for them to grow up. These facts made it easy to hunt many beavers. European tools like axes could chop through beaver lodges and dams. Guns, knives, and spears also made hunting these calm animals simple.

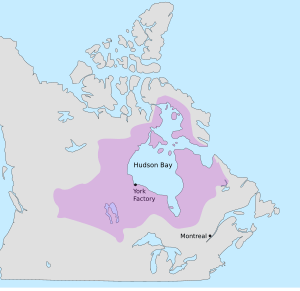

Innis concluded that as beavers disappeared in eastern areas, traders had to go further west and north. They needed to find new sources of fur. The fur trade then became about moving supplies and furs over longer and longer distances. The waterways in beaver areas were very important for this. They played a key role in the economic growth of northern North America.

A Look at Fur Trade History

Harold Innis carefully tracked the fur trade for over 400 years. This period stretched from the early 1500s to the 1920s. It was a time of many fights. There were wars between French and English forces. Different First Nations groups also fought each other. The story also includes smart trading and business rivalries.

Innis began by describing the first meetings. European fishing fleets met eastern First Nations tribes in the early 1500s. The French settlement at Quebec was founded in 1608 by Samuel de Champlain. The colony, called New France, relied on furs to survive. Champlain worked with the Huron Confederacy and their friends. They fought against the Iroquois Confederacy to control the fur trade.

Rivalries and Expansion in the Fur Trade

As New France grew, French colonists traveled north and west. These traders were first called coureurs de bois, then voyageurs. They searched for new fur supplies. Meanwhile, their British rivals set up trading posts in the north. These posts were run by the Hudson's Bay Company.

The business competition continued after the British took over New France in 1759. The North West Company was then started by Scottish merchants from Montreal. These merchants were very active. The two companies built trading posts far west of Lake Superior and Hudson Bay. The Nor'Westers were more daring. They traveled north to the Arctic Ocean using the Mackenzie River. They also went west to the Pacific Ocean.

The strong competition ended in 1821. The two companies joined together to form a single Hudson's Bay Company. The company finally gave up its control of the northwest in 1869. They sold their land to Canada. This happened because profits and demand for furs had dropped.

The Decline of the Fur Trade

Innis also wrote about the end of the fur trade's power. Silk hats and fancy fox fur became more popular than beaver. Steamboats came to the West, and railways were built. This brought more competition from independent traders. New companies from the American West also joined in. Firms from Winnipeg, Edmonton, and Vancouver also competed.

Better transportation meant more control over the trade. It also meant cheaper goods. More control led to more checks, better accounting, and careful rules. It also meant less fighting and more expansion of trading areas. But there were problems. It was hard to watch over large areas. Some rules were too strict. More farming also meant people relied less on hunting for food.

Innis ended by noting that in 1927, the Hudson's Bay Company invested in fox farms. These farms were in Prince Edward Island. This made the future of wild fur trading uncertain. Innis felt it was time to study how to protect Canada's natural resources. In the end, there were many goods but few furs. This showed the fur trade was no longer a main part of the economy.

Furs, Culture, and New Tools

Innis saw the fur trade as a meeting of two cultures: European and North American. He focused on how new tools and ways of doing things changed everything. The trade became important in the late 1500s. This was when the beaver hat became popular in Europe.

However, Innis stressed that First Nations people really wanted European goods. They wanted things like iron tools.

Imagine how important iron was to a culture that used bone, wood, bark, and stone! Cooking in wooden pots with hot stones was replaced by easy-to-carry kettles. Iron axes and hatchets made work much easier. Sewing became simpler with awls instead of bone needles. For First Nations people, iron goods were extremely important. The French were known as the gens du fer, or "iron people."

Guns, knives, and metal spears also made hunting easier and faster. But Innis pointed out that these convenient goods came with a high cost. First Nations people became dependent on European traders. They needed new supplies, bullets, and spare parts. Hunting more efficiently with guns led to beavers being hunted too much. This forced hunters to go into new areas to find more furs. This competition often led to fights.

Innis wrote that wars between tribes, which were not too bad with bows and arrows, became terrible with guns. Things got even worse because First Nations people had no protection against European diseases. Diseases like smallpox constantly swept through their communities. They killed many people. Also, European alcohol like rum and brandy caused sickness, conflict, and addiction.

Innis often highlighted the terrible effects of contact between advanced European culture and traditional First Nations societies. He wrote that First Nations people's reliance on beaver pelts for European iron goods "disturbed the balance" they had before Europeans arrived.

How Cultures Depended on Each Other

Just as First Nations people needed European goods, European traders relied on First Nations tools and skills. Birch-bark canoes helped traders travel in spring, summer, and fall. snowshoes and toboggans made winter travel possible. Indian corn, pemmican, and wild game provided food and clothing. Innis also noted that First Nations people had amazing knowledge of the forests. They knew the habits of the animals they hunted.

Historian John Watson said Innis's study of the fur trade was groundbreaking. He made cultural factors central to how economies grew. Watson called The Fur Trade in Canada a "complex analysis." It looked at three different cultural groups. These were European customers who bought hats, colonial settlers who traded furs, and First Nations people who relied on European tools.

Innis also noted how traders depended on First Nations people. He suggested First Nations people were in charge in early trading. He wrote that French traders quickly learned First Nations languages, customs, and ways of life.

The trader encouraged the best hunters. They urged First Nations people to hunt beaver. They guided their canoe fleets to meeting places. Alliances were made, and wars were even supported to get more fur. Goods were traded that would make First Nations people want to hunt beaver.

Innis wrote that the French used Christianity to make First Nations people more willing to trade. They encouraged war or peace to gain First Nations support. He noted these actions made trading more expensive. This lowered profits and helped monopolies grow.

Economic Effects of Key Products

Canada as a "Marginal" Colony

Innis's book ends with a 15-page conclusion. It explains how important key products, like furs, were to the growth of colonies. It also looks at how this trade affected Britain and France. Innis wrote that North America's culture came from Europe. He was interested in how this huge new land affected European culture.

He noted that European settlers in North America survived by learning from First Nations people. But they also wanted to keep their European way of life. They did this by sending goods not found in Europe back home. In return, they got manufactured products. For Canada, the first such goods were cod fish and beaver fur. Later, other key products included lumber, paper, wheat, gold, and other metals.

Innis believed this two-way trade had big effects. The colony focused on making these key products. The home country made finished goods. So, the trade helped factories grow in Europe. But the colony stayed focused on producing raw materials. Over time, Canada's farming, industry, transportation, trade, money, and government all became focused on making key products for industrial Britain. Later, this was also true for the fast-growing United States. This constant reliance on key products made Canadians "hewers of wood and drawers of water." This means they mainly did the hard work of getting raw materials.

Innis concluded that Canada's economic history was shaped by the difference between the "center" (Europe) and the "edge" (Canada). For him, Canada's economy started as a big trading system. It was based on the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes. One end was in Europe, and the other was in North America. It was a system that crossed both oceans and the continent.

The Idea of "Cyclones" in the Economy

Innis argued that a country relying on exporting key products would always be at risk. It could be hurt by problems with supply or changes in what buyers wanted. For example, a small change in fashion in London or Paris could badly affect a colony that depended on exporting beaver fur.

Innis created the idea of "cyclonics" to explain problems. These problems happened when new tools led to quickly using up, and then running out of, key products. For instance, European guns made beaver hunting more efficient. But this led to beavers being hunted too much. Traders then had to go on expensive, long trips to find new fur sources. Later, the decline of white pine, important for lumber, led to making pulp and paper from spruce trees.

Shifts from one key product to another caused constant economic "cyclones." Innis wrote in 1929 that Canadians had used up their energy. They had opened up the West. They developed mines, power plants, and paper mills. They built railways, grain elevators, and cities.

For Innis, imported industrial tools led to quickly using up resources. This caused too much production, waste, running out of resources, and economic collapse. These were the problems for countries like Canada that produced key products.

Politics and the Trade of Key Products

Innis famously wrote that Canada "emerged not in spite of geography but because of it." He argued that Canada's borders roughly match the fur-trading areas of northern North America. The increased demand for furs, like beaver, certainly led to more exploration westward.

Innis believed that the shift from furs to lumber led to European immigration. It also led to the fast settling of the West. The "coffin ships" that carried lumber to Europe brought back immigrants as a "return cargo." Exporting lumber, and later wheat, needed better transportation. This meant building canals and railways.

The costs of these transportation improvements were a big reason for the Act of Union. This act joined Upper and Lower Canada in 1840–41. It also led to the political Confederation of Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia in 1867. Relying on key products in a huge country led to strong central banks. It also led to a strong federal government. This created a mix of government ownership and private business in Canada.

The Hudson's Bay Company's monopoly encouraged central control. It also led to military action and hints of nationalism. Innis concluded that keeping ties with France and Britain encouraged different ways of doing things and more tolerance. He added that "Canada has remained fundamentally a product of Europe."

What People Thought of the Book

Historian Carl Berger noted that it took 15 years to sell the first thousand copies of The Fur Trade in Canada. Yet, he wrote, it is one of the most important books in Canadian history. According to Berger, Innis showed that Canada was not a weak country. Its existence was not just about human will. Instead, Innis showed that river systems and the Canadian Shield created a natural unity. He believed that "Confederation was, in a sense, a political reflection of the natural coherence of northern America."

Berger added that Innis explored the links between economic changes and political developments. Innis's ideas led to a new way of understanding Canadian history. Innis also "placed Indian culture at the centre of his study of the fur trade." He was the first to properly explain how First Nations society broke down under European capitalism. Unlike other historians, Innis highlighted the contributions of First Nations people. He wrote, "We have not yet realized that the Indian and his culture were fundamental to the growth of Canadian institutions."

Berger mentioned a "sense of fatalism and determinism" in Innis's economic history. He added that for Innis, real-world facts shaped history. Language, religion, or social beliefs were less important. Berger felt that Innis's history was "dehumanized" in this way.

However, biographer John Watson argued that The Fur Trade in Canada is "more complex, more universal, and less rigidly deterministic than commonly accepted." Watson pointed out that Innis cared deeply about culture's role in economic history. He was also aware of how cultures broke down when advanced tools were introduced. Watson wrote, "Innis never uses the staple as anything more than a focusing point around which to examine the interplay of cultures and empires."

Images for kids