The Phantom Tollbooth facts for kids

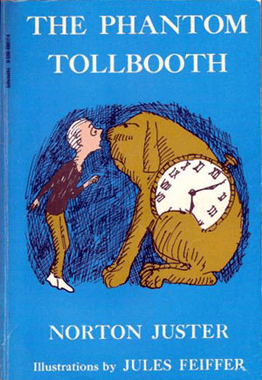

Milo and Tock on the cover of the book (same Feiffer illustration as 1st ed.)

|

|

| Author | Norton Juster |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Jules Feiffer |

| Country | United States |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Publisher | Epstein & Carroll, distributed by Random House |

|

Publication date

|

August 12, 1961 |

| Pages | 255 |

| ISBN | 978-0-394-82037-8 |

| OCLC | 576002319 |

| LC Class | PZ7.J98 Ph |

The Phantom Tollbooth is an exciting fantasy adventure novel for children. It was written by Norton Juster and has cool drawings by Jules Feiffer. The book came out in 1961.

The story is about a boy named Milo who is super bored with everything. One day, he gets a mysterious magic tollbooth. Since he has nothing else to do, he drives his toy car through it. This takes him to a magical place called the Kingdom of Wisdom.

The Kingdom of Wisdom used to be great but is now in trouble. Milo meets two loyal friends: a dog named Tock and a bug called the Humbug. Together, they go on a big adventure. Their mission is to rescue the kingdom's princesses, Rhyme and Reason, who are trapped in the Castle in the Air.

During his journey, Milo learns many important lessons. He discovers how much fun learning can be, and his boredom disappears. The book is also full of clever puns and wordplay. For example, Milo accidentally drives to an island called "Conclusions," showing the funny side of everyday sayings.

In 1958, Norton Juster received money to write a children's book about cities. But he found it hard to make progress. So, he started writing what became The Phantom Tollbooth instead. This was his very first book.

His housemate, Jules Feiffer, who was a cartoonist, became interested in the story. Jason Epstein, an editor at Random House, decided to publish the book. The Phantom Tollbooth received amazing reviews and has sold over three million copies. This was much more than anyone expected! The book has been turned into a movie, an opera, and a play. It has also been translated into many different languages.

Even though it's an adventure story, a big message in the book is how important it is to love education. Through his journey, Milo uses what he learned in school. He grows as a person and starts to enjoy life, which he found boring before.

Some people compare the book to Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll. They also compare it to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum. Maurice Sendak, a famous author, once quoted a critic who compared The Phantom Tollbooth to Pilgrim’s Progress. The critic said that just as Pilgrim’s Progress is about waking up a lazy spirit, The Phantom Tollbooth is about waking up a lazy mind.

Contents

Story Summary

Milo is a boy who finds everything boring. He comes home from school one day and finds a mysterious package. Inside are a small tollbooth and a map of "the Lands Beyond." This map shows the Kingdom of Wisdom. A note with the package says, "For Milo, who has plenty of time."

The package also has a sign telling him to pick a destination. Milo decides to go to Dictionopolis, thinking it's just a game. He drives his toy car through the tollbooth. Suddenly, he's on a real road that is definitely not in his apartment!

Starting the Journey

Milo begins his trip in a pleasant place called Expectations. This is where the road to Wisdom starts. In Expectations, he asks the Whether Man for directions. The Whether Man talks endlessly and doesn't help much.

As Milo drives, he starts daydreaming. He soon gets lost in the Doldrums, a dull, colorless place where nothing ever happens. Milo starts acting like the people who live there, called Lethargarians. They spend their time "killing time."

Suddenly, Tock arrives! Tock is a talking, giant dog with an alarm clock on each side. He's a "watchdog" who tells Milo that only by thinking can he escape the Doldrums. Milo starts thinking, and soon he's back on the road. The watchdog joins him on his adventure through Wisdom.

Dictionopolis and the Word Market

Milo and Tock travel to Dictionopolis. This is one of the two main cities in the Kingdom of Wisdom. It's home to King Azaz the Unabridged. They meet King Azaz's advisors and visit the Word Market. Here, words and letters are sold, which are very important for the world.

A fight breaks out between the Spelling Bee and the loud Humbug. This causes the market to close. Milo and Tock are then arrested by the very short Officer Shrift. In prison, Milo meets the Which (not a witch!). Her real name is Faintly Macabre. She used to decide which words should be used in Wisdom.

She tells Milo a sad story. King Azaz and his brother, the Mathemagician, had two adopted younger sisters, Rhyme and Reason. Everyone came to the princesses to solve their problems. Everything was peaceful until the rulers disagreed with the princesses. Rhyme and Reason said that letters (which Azaz loved) and numbers (which the Mathemagician loved) were equally important. Because of this, the brothers banished the princesses to the Castle in the Air. Since then, the land has had no Rhyme or Reason.

The Quest Begins

Milo and Tock leave the dungeon. King Azaz invites them to a special banquet where guests literally eat their words. After the meal, King Azaz convinces Milo and Tock to go on a dangerous quest to rescue the princesses. Azaz also tricks the Humbug into becoming their guide.

The boy, dog, and insect set off for Digitopolis. This is the Mathemagician's city. They need his approval before they can start their quest.

Strange Encounters

Along the way, they meet many interesting characters. They meet Alec Bings, a small boy who floats in the air and sees through things. He will grow down until he reaches the ground. They also meet the world's smallest giant, the biggest dwarf, the thinnest fat man, and the fattest thin man. It turns out they are all just one regular man! Milo then loses time helping Chroma the Great, a conductor whose orchestra creates all the colors of the world.

They meet a twelve-sided creature called the Dodecahedron. He leads them to Digitopolis. There, they meet the Mathemagician. He is still angry at Azaz and won't agree to anything his brother approved. Milo cleverly gets him to say he will allow the quest if Milo can prove the brothers have agreed on anything since banishing the princesses. To the Mathemagician's surprise, Milo shows that they agreed to disagree! So, the Mathemagician reluctantly gives his permission.

Reaching the Castle in the Air

In the Mountains of Ignorance, the travelers face scary demons. These include the Terrible Trivium and the Gelatinous Giant. After overcoming these challenges and their own fears, they finally reach the Castle in the Air. Princesses Rhyme and Reason are happy to see Milo and agree to return to Wisdom.

The demons can't get into the castle, so they cut it loose! The castle starts to float away. But Milo remembers that Tock can carry them down because "time flies." The demons chase them, but the armies of Wisdom arrive and fight them off. Rhyme and Reason heal the problems in the Kingdom of Wisdom. Azaz and the Mathemagician become friends again. Everyone celebrates for three days!

The Return Home

Milo says goodbye and drives back through the tollbooth. Suddenly, he's back in his own room! He realizes he's only been gone for an hour, even though his journey felt like weeks. The next day, he plans to return to the kingdom. But when he gets home from school, the tollbooth is gone.

Instead, there's a note that says, "For Milo, who now knows the way." The note explains that the tollbooth is being sent to another child who needs help finding direction in life. Milo is a little sad but understands. He looks at the world around him, and it now seems interesting. He realizes that even if he could go back, he might not have time because there's so much to do right where he is.

How the Book Was Written

Norton Juster, who was an architect, lived in Brooklyn. In June 1960, he received a grant to write a children's book about cities. Juster believed that young people would soon be in charge of cities. Many kids lived in the suburbs and didn't know much about them. He wanted to help children notice and appreciate the world around them.

Milo continued to think of all sorts of things; of the many detours and wrong turns that were so easy to take, of how fine it was to be moving and, most of all, of how much could be accomplished with just a little thought.

Juster started with lots of excitement, but then he got stuck. He had too many notes and wasn't making progress. He took a short break and decided to put the cities book aside. He wanted to find inspiration for a different writing project.

Juster felt guilty about not working on the cities book. This guilt led him to write small stories about a boy named Milo. He started turning these into a book. Juster even quit his job so he could focus on writing. He was inspired by a boy who asked him about infinity. Juster wanted to finish the story about "a boy who asked too many questions."

Juster shared his house with cartoonist Jules Feiffer. Feiffer could hear Juster pacing at night. He was surprised to learn his friend's sleeplessness was not from the cities book, but from a book about a boy. Juster showed Feiffer his draft. Without being asked, Feiffer started drawing pictures for it.

Feiffer knew Judy Sheftel, who helped connect writers with publishers. Sheftel got Jason Epstein, an editor at Random House, to look at the story. Some people at Random House thought the book's words were too hard for kids. At that time, teachers thought children's books should only use words kids already knew. But Epstein liked the book. Based on seven chapters and an outline, he decided to buy it.

Juster did the cooking for the housemates. So, if Feiffer wanted to eat, he had to do the drawings! Feiffer quickly realized the book needed special illustrations. He thought of the drawings John Tenniel made for Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Even though Feiffer was a well-known artist, he wasn't sure he could do the book justice. Feiffer really liked his drawing of the demons late in the book. It was different from his usual style and was inspired by Gustave Doré's drawings.

It became a fun challenge for them. Feiffer tried to draw things the way he wanted. Juster tried to describe things that seemed impossible to sketch. For example, the Triple Demons of Compromise: one short and fat, one tall and thin, and the third exactly like the first two! Feiffer got his revenge by drawing Juster as the Whether Man, wearing a toga.

They made many changes to the book. The main character's name was originally Tony. His parents were completely removed from the story. They also took out parts that tried to explain how the tollbooth package arrived. Milo's age was also removed. Early versions said he was eight or nine. Juster decided not to state his age so that older readers wouldn't think they were too old for the book.

Inspirations for the Story

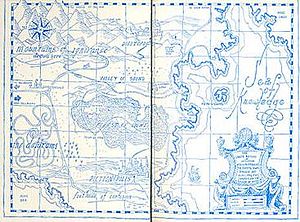

The Phantom Tollbooth includes ideas from many other works. These were books and stories Juster loved when he was growing up. Some of his favorite childhood books, like The Wind in the Willows, had maps on the inside covers. Juster really wanted one for his book. He even drew a sketch and asked Feiffer to draw it in his own style.

Juster was also inspired by his father Samuel's love of puns. The book is full of them! When Juster was a child, he listened to the radio a lot. He said that having to imagine the action while listening to radio serials helped inspire The Phantom Tollbooth. This also led to the character of Tock. Tock was based on a sidekick named Jim Fairfield from a show called Jack Armstrong, the All-American Boy. Jim gave Tock his wisdom, bravery, and love for adventure.

"Oh dear, all those words again," thought Milo as he climbed into the wagon with Tock and the cabinet members. "How are you going to make it move? It doesn't have a—"

"Be very quiet," advised the duke, "for it goes without saying."

And, sure enough, as soon as they were all quite still, it began to move through the streets, and in a very short time they arrived at the royal palace.

As a child, Juster had a condition called synesthesia. This meant he could only do math by connecting numbers to colors. He remembered that this condition also affected how he linked words. He said, "One of the things I always did was think literally when I heard words. On the Lone Ranger [radio show] they would say, 'Here come the Injuns!' and I always had an image of engines, of train engines."

Some events in the book come from Juster's own life. In Digitopolis, there's a Numbers Mine where gem-like numbers are dug up. This reminded Juster of one of his architecture professors. The professor used to compare numbers and equations to jewels. The Marx Brothers films were a favorite for Juster as a child. His father would quote long parts from the movies. This inspired the endless funny puns in the book.

Juster grew up in a Jewish-American home where his parents expected high achievements. He knew a lot about expectations. However, many of his parents' hopes were focused on his older brother, who was a brilliant student. The Terrible Trivium is a polite demon who gives the questers pointless tasks. Juster created him to represent his own habit of avoiding what he should be doing. For example, he avoided his grant project to write The Phantom Tollbooth. Juster also used Feiffer's life experiences. The Whether Man's saying, "Expect everything, I always say, and the unexpected never happens," was a favorite saying of Feiffer's mother.

Juster had not read Alice's Adventures in Wonderland when he wrote The Phantom Tollbooth. But both books are about a bored child who enters a world of strange logic. They have often been compared. Milo's conversation with the Whether Man, which leaves him confused, is like Alice's talk with the Cheshire Cat. Both books also explore questions of authority and justice. The Queen of Hearts' unfair justice is similar to Officer Shrift's actions, though less violent.

Alice's rulers represent the authority figures of Victorian childhood. They rule completely. Milo, a child from after World War II, travels through a more organized world. His quest has a clear purpose, unlike Alice's frustrating journey. The outcome is also different: Milo fixes his kingdom, while Alice overturns hers. Carroll leaves us wondering if Alice learned anything. But Juster makes it clear that Milo has gained important skills he will need for life.

See also

In Spanish: The Phantom Tollbooth para niños

In Spanish: The Phantom Tollbooth para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |