John Tenniel facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Tenniel

|

|

|---|---|

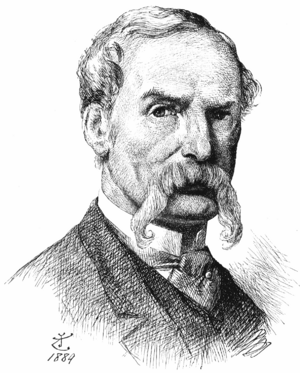

Self-portrait of John Tenniel, c. 1889

|

|

| Born | 28 February 1820 London, England

|

| Died | 25 February 1914 (aged 93) London, England

|

| Nationality | British |

| Known for | Illustration, children's literature, political cartoons |

Sir John Tenniel (born February 28, 1820 – died February 25, 1914) was a famous English illustrator and political cartoonist. He was very important in the second half of the 1800s. He studied at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. In 1893, he was made a knight for his amazing art. He was the first illustrator or cartoonist to receive such an honor.

Tenniel is best known for two main things. First, he was the main political cartoonist for Punch magazine for over 50 years. Second, he created the famous drawings for Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1871). Tenniel's detailed black-and-white drawings are still the most recognized images of the Alice characters. The writer Bryan Talbot even said, "Carroll never describes the Mad Hatter: our image of him is pure Tenniel."

Contents

John Tenniel's Early Life

John Tenniel was born in Bayswater, West London. His father, John Baptist Tenniel, taught fencing and dancing. His mother was Eliza Maria Tenniel. John had five brothers and sisters. He was a quiet and shy person, even as a child. He liked to stay out of the spotlight.

In 1840, Tenniel had an accident while practicing fencing with his father. He got a serious eye injury. Over time, he slowly lost sight in his right eye. He never told his father how bad the injury was, because he did not want to upset him.

Even though he was interested in serious art, Tenniel was also known for his humor. He became friends with Charles Keene. This friendship helped him develop his talent for drawing funny pictures.

How Tenniel Trained as an Artist

Tenniel became a student at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1842. He was accepted because he had made many copies of old sculptures. This allowed him to continue his art education.

Tenniel did not always agree with the teaching methods at the Royal Academy. So, he decided to teach himself a lot of things. He studied classical sculptures by painting them. He also drew classical statues at London's Townley Gallery. He copied pictures from books about costumes and armor at the British Museum. He drew animals from the zoo in Regent's Park. He also drew actors from London theaters.

These studies taught Tenniel to love small details. However, he sometimes became impatient with his work. He was happiest when he could draw things from his memory. He had a great memory, which helped him a lot.

Another way Tenniel trained was by joining an artists' group. This group was free from the strict rules of the Academy. In the mid-1840s, he joined the Artist's Society. Here, he started to become known as a satirical artist.

Tenniel's First Art Jobs

Tenniel's first book illustration was for Samuel Carter Hall's The Book of British Ballads in 1842. Around this time, art competitions were happening in London. The government wanted to encourage English art.

Tenniel planned to enter a competition in 1845 to design murals for the new Palace of Westminster. He missed the deadline, but he still submitted a large drawing called An Allegory of Justice. For this, he won £200 and was asked to paint a fresco in the House of Lords.

Working for Punch Magazine

Tenniel became the main cartoon artist for Punch magazine. This made him very important. He saw many big changes happening in Britain. He used his art to push for political and social improvements. His drawings were often funny, sometimes strong, and showed his views on the world.

In 1850, Mark Lemon invited him to join Punch as a cartoonist. He was chosen because of his recent drawings for Aesop's Fables. His first drawing for Punch was called "Lord Jack the Giant Killer." It showed Lord John Russell fighting Cardinal Wiseman.

Tenniel's famous lion drawings first appeared in 1852. He also drew his first obituary cartoon that year. Slowly, he took over drawing the main political cartoon each week. John Leech, another cartoonist, was happy to let Tenniel do this. Leech preferred to draw pictures of everyday life.

In 1861, Tenniel was offered Leech's position as the main political cartoonist. Tenniel always tried to be fair and calm, even when dealing with big social and political issues. When Leech died in 1864, Tenniel continued the work alone. He rarely missed a single week.

Tenniel had to follow the ideas of the Punch editors. They often got their ideas from The Times newspaper and from political discussions in Parliament. Tenniel's cartoons could have a strong impact. Punch often focused on issues like working-class rights, labor, war, and the economy. These became the topics for Tenniel's cartoons.

For example, his drawing "An Unequal Match" was published in Punch in 1881. It showed a police officer fighting a criminal with only a baton. This drawing aimed to show the public that policing methods needed to change.

Tenniel drew 2,165 cartoons for Punch. This magazine was liberal and active in politics. It often showed what the British public was thinking. So, Tenniel's cartoons often represented the feelings of most British people for many years.

He also contributed about 2,300 smaller drawings. He made many double-page cartoons for Punch's Almanac and other special issues. He also created 250 designs for Punch's Pocket-books. By 1866, he was earning a good salary from Punch, about £800 a year.

Illustrating Alice in Wonderland

Even though he drew thousands of political cartoons, Tenniel is most famous for his illustrations for the Alice books. He drew 92 pictures for Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There (1871).

Lewis Carroll first tried to illustrate Wonderland himself. But his drawing skills were not very good. An engraver named Orlando Jewitt suggested that Carroll hire a professional artist. Carroll read Punch magazine regularly, so he knew Tenniel's work. In 1865, Tenniel and Carroll talked a lot before Tenniel started drawing for the first Alice book.

The first printing of 2,000 copies was sold in the United States. This was because Tenniel was not happy with the print quality. A new edition was released in December 1865, dated 1866. It quickly became a huge success, making Tenniel even more famous. His drawings for both Alice books are now some of the most well-known book illustrations ever. After 1872, when the Alice projects were done, Tenniel mostly stopped illustrating books.

Tenniel's Alice illustrations were carved into wooden blocks by the Brothers Dalziel. These blocks were then used to make copies for printing the books. The original wooden blocks are kept at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, England.

The bronze Alice in Wonderland sculpture (1959) in Central Park in Manhattan, New York City, is based on Tenniel's famous illustrations.

Tenniel's Artistic Style

Attention to Detail

After the 1850s, Tenniel's style became more modern. He started adding more details to the backgrounds and figures in his drawings. This made his illustrations more specific. They showed exact moments in time, places, and individual characters.

Tenniel also became very interested in drawing different types of people and their expressions. This carried over into his Alice illustrations. Many people called this his "theatrical" style. It probably came from his early interest in drawing caricatures. For example, in his Punch drawings, he would give human-like personalities to objects in the environment.

Another change in his style was how he used shaded lines. He started using strong, hand-drawn lines to make darker areas more intense.

The "Grotesque" in His Art

One reason Lewis Carroll wanted Tenniel to illustrate the Alice books was his "grotesque" style. This style could make the real world seem a bit strange or unreliable. Tenniel's grotesque style often featured dark, imaginative drawings of exaggerated fantasy creatures. He would carefully draw them with clear outlines.

He often used animal heads on human bodies, or vice versa. This was similar to what Grandville did in a French satirical magazine. In Tenniel's Alice illustrations, the grotesque also appears when beings and things merge. It also shows up in strange body changes, like when Alice drinks the potion and grows very big. The most famous example of his grotesque style is his drawing of the Jabberwock in Alice.

The Alice illustrations mix fantasy with reality. Scholars say Tenniel's style changed in the late 1850s to include more realism. For the grotesque style to work, it needs to make *our* world seem transformed, not just a fantasy world. The illustrations subtly remind us of the real world. Some scenes look like a medieval town or a Georgian house. The White Rabbit wears a checked jacket. Also, Tenniel followed Carroll's text very closely. This helps readers see how the words and pictures match. These realistic touches help convince readers that the strange characters in Wonderland are real within their story.

How Pictures and Text Work Together in Alice

One special thing about the Alice books is how Tenniel's illustrations are placed on the pages. The pictures and text are closely linked. Carroll and Tenniel showed this in different ways. Sometimes, two important sentences would surround an image. This helped to show the exact moment Tenniel was illustrating. This way of placing pictures with text makes them feel more immediate and dramatic. Other times, less frequent illustrations worked like captions for the text.

Another connection between pictures and text is the use of wider and narrower illustrations. Wider pictures were usually placed in the center of the page. Narrower ones were "let in" or placed right next to the margin, alongside a thin column of text. The words would run parallel to the picture. For example, when Alice says, "Oh, my poor little feet!", the words appear at the bottom of the page, right next to her feet in the drawing. Some of these narrower illustrations are shaped like an "L". These are very important and some of his most memorable works. The top or bottom of these "L"-shaped pictures takes up the full width of the page. But the other end leaves space on one side for text.

Selected Book Illustrations by Tenniel

Books Illustrated Entirely by Tenniel

- Juvenile Verse and Picture Book (1846)

- Undine (1846)

- Aesop's Fables (1848)

- Blair's Grave (1858)

- Shirley Brooks' The Gordian Knot (1860)

- Shirley Brooks' The Silver Cord (1861)

- Moore's Lalla Rookh (1861), 69 drawings

- Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1866)

- The Mirage of Life (1867)

- Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking-Glass (1870)

- Lewis Carroll's The Nursery "Alice" (1890)

Books with Tenniel's Collaborations

- Thomas Ingoldsby's The Ingoldsby Legends

- Pollok's Course of Time (1857)

- The Poets of the Nineteenth Century (1858)

- Edgar Allan Poe's "The Raven," in The Poetical Works of Edgar Allan Poe (1858)

- Home Affections (1858)

- Cholmondeley Pennell's Puck on Pegasus (1863)

- The Arabian Nights (1863)

- L. B. White, English Sacred Poetry of the Olden Time (1864)

- Legends and Lyrics (1865)

- Martin Farquhar Tupper's Proverbial Philosophy

- Barry Cornwall's Dramatic Scenes: With other poems (1857)

Retirement and Legacy

An important honor came to Tenniel when he was older. In 1893, Queen Victoria made him a knight for his public service. This was the first time an illustrator or cartoonist had received such an honor. His fellow artists saw his knighthood as a thank you for "raising what had been a fairly lowly profession to an unprecedented level of respectability." By becoming a knight, Tenniel improved the social standing of black-and-white illustrators. It also brought new recognition to his profession.

When he retired in January 1901, Tenniel was honored with a special dinner. AJ Balfour, a leader in the government, spoke at the dinner. He called Tenniel "a great artist and a great gentleman."

Tenniel passed away on February 25, 1914, just three days before his 94th birthday. He was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery in London.

Tenniel had a big impact on the political feelings of his time. His Punch cartoons were able to influence political groups and people. Two days after he died, The Daily Graphic newspaper said that Tenniel "had an influence on the political feeling of his time which is hardly measurable." They added that people always looked to the Punch cartoon to understand national and international situations.

Because his political cartoons were published weekly for over 50 years, Tenniel became very famous. He was one of the most published illustrators in Victorian Britain. As a Punch cartoonist, he was also one of the best observers of British society. He was a key part of a powerful newspaper force. In 1914, a journalist from the New-York Tribune called John Tenniel "one of the greatest intellectual forces of his time."

Public shows of Sir John Tenniel's work were held in 1895 and 1900. Tenniel also created one of the mosaics, Leonardo da Vinci, in the South Court of the Victoria and Albert Museum. His watercolor drawings sometimes appeared in exhibitions of the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours. He had been elected to this group in 1874.

Tenniel Close, a street in Bayswater near where his old studio was, is named after him.

Gallery

-

The Jabberwock, illustrated by John Tenniel for Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking-Glass, which includes the poem "Jabberwocky"

-

Dropping the Pilot, a 1890 Punch cartoon about Otto von Bismarck's dismissal

See also

In Spanish: John Tenniel para niños

In Spanish: John Tenniel para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |