One Thousand and One Nights facts for kids

|

Cassim in the cave, by Maxfield Parrish, 1909, from the story "Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves"

|

|

| Author | various |

|---|---|

| Country | Middle East |

| Language | Arabic language |

| Subject | Story |

| Genre | Frame story, Folk tales |

| Set in | Middle Ages |

The Book of One Thousand and One Nights is a very old collection of stories. Most of these tales come from Arabia and Persia. Some also come from India, Central Asia, and China. All these stories were later gathered into one big book.

The stories are like layers, one inside another:

- The main story is about Queen Scheherazade. She tells stories to her husband, the Sultan or King Sheheryar. She does this every night to keep herself safe from being put to death.

- Inside her story, there are many other famous tales. These include "Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves" and "Aladdin and the Magic Lamp."

- Sometimes, within those stories, another character tells a story. It's like a story within a story within a story!

Even though the first European translation came out in 1704, these stories might have influenced Western culture much earlier. Writers in Medieval Spain translated many Arabic works. This included not just math and philosophy, but also Arab fiction. For example, you can see ideas from the Nights in El Conde Lucanor by Juan Manuel.

Ideas from the Nights also spread beyond Spain. You can find similar themes in famous works like The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer. In one of Chaucer's stories, a hero rides a flying brass horse, just like in some Nights tales. Also, Boccaccio's Decameron has echoes of these stories. It seems the tale of Shahriyar and Shahzaman was known in many places. The stories even reached the Balkans. A Romanian translation existed by the 1600s.

Contents

The Nights in Arab Culture

It might surprise you, but the Nights wasn't always super popular in the Arab world. It's not often listed among the most important books from that time. Also, not many old handwritten copies exist from before the 1700s.

In Medieval Arab culture, fiction stories were not seen as important as poetry. People sometimes called these tales khurafa, meaning "unlikely fantasies." They thought these stories were only good for entertaining women and children. Even today, some people in the Arab world don't think highly of the Nights. They might say the stories are unbelievable, childish, or not well-written.

A Timeline of the Nights

Scholars have put together a timeline of how The Nights became known:

- Early 800s: The oldest known Arabic handwritten pages are found in Syria. They are titled Kitab Hadith Alf Layla ("The Book of the Tale of the Thousand Nights").

- 900s: The book Hezār Afsān (meaning "Thousand Stories" in Persian) is mentioned in Baghdad. It's believed to be the origin of the frame story about Scheherazade.

- 1000s: Another mention of The Thousand Nights appears. It's described as an Arabic translation of the Persian Hezār Afsān.

- 1100s: A document from Cairo mentions a bookseller lending a copy of The Thousand and One Nights. This is the first time the full title appears.

- 1300s: A Syrian handwritten copy with about 300 tales is kept in Paris, France.

- 1704: Antoine Galland creates the first European translation in French. This version made the stories very popular in Europe.

- Early 1700s: An English version called Arabian Nights' Entertainments appears. This is the first time the common English title is used.

- 1814: The first existing Arabic printed version is published in Calcutta, India.

- 1835: The Bulaq version is printed by the Egyptian government. This is the oldest printed Arabic version by a non-European publisher.

- Late 1800s: Famous English translations are published by John Payne and Sir Richard Francis Burton. These helped make the stories even more widely known.

- 1984: Muhsin Mahdi publishes an Arabic edition based on the oldest surviving Arabic manuscript. This is considered a very important version for scholars.

- 1990: Husain Haddawy publishes an English translation of Mahdi's version.

- 2008: A new English translation is released by Penguin Classics.

Related stories

Images for kids

-

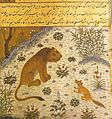

A page from Kelileh va Demneh dated 1429, from Herat, a Persian version of the original ancient Indian Panchatantra – depicts the manipulative jackal-vizier, Dimna, trying to lead his lion-king into war.

-

Sindbad and the Valley of Diamonds, from the Second Voyage.

-

Harun ar-Rashid, a leading character of the 1001 Nights

See also

In Spanish: Las mil y una noches para niños

In Spanish: Las mil y una noches para niños