The bomber will always get through facts for kids

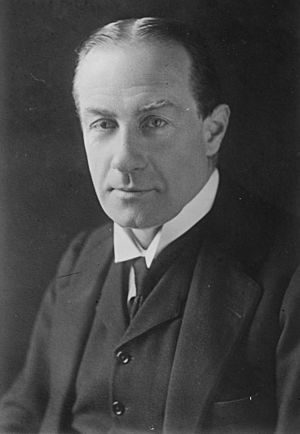

"The bomber will always get through" was a famous phrase spoken by Stanley Baldwin, a British leader, in 1932. He gave a speech called "A Fear for the Future" to the British Parliament. In his speech, Baldwin said that new bomber aircraft were so powerful they could destroy cities. He believed there was little anyone could do to stop them. He even suggested that future wars might mean "killing more women and children more quickly than the enemy" to win.

At that time, airplanes were getting much better very fast. New ways of building planes made them bigger and stronger. For a while, large multi-engine bombers were faster than the single-engine fighter aircraft meant to stop them. This problem became even worse with night bombing, which made it almost impossible to see and stop the planes.

This situation did not last long. By the mid-1930s, fighters also improved a lot. They became fast enough to catch even the quickest bombers. Also, the invention of radar helped a lot. Radar was an early warning system that gave fighters enough time to get into the air before bombers arrived.

The Battle of Britain in World War II showed that Baldwin was not entirely right. Many German bombers did reach British cities and caused damage. But they did not destroy Britain's factories or break the people's spirit. Also, many bombers were shot down. The Germans lost so many planes that they had to stop their bombing campaign after a few months.

Later in the war, Britain and the United States built many bombers. Enough of these bombers got through to damage Germany's factories. But this came at a high cost in lost bombers. This success was mainly because the Allies developed long-range escort fighters. These fighters could protect the bombers all the way to Germany.

Contents

Understanding Baldwin's Idea

Baldwin did not want Britain to get rid of all its weapons. But he thought that having "great armaments" (lots of weapons) would always lead to war. However, by November 1932, he felt that Great Britain could no longer reduce its weapons alone.

People often used this speech against Baldwin. Some said it showed that building more weapons was useless. Others said it proved that reducing weapons was useless.

Early Ideas About Air War

Many thinkers believed that future wars would be won only by bombing an enemy's military and factories from the air. An Italian general named Giulio Douhet wrote a book called The Command of the Air. He was a key thinker in this idea.

Before World War I, H. G. Wells wrote a book called The War in the Air. It suggested that air war could not be "won" just by bombing. But in 1936, his film Things to Come showed a war starting with huge air attacks on a city called "Everytown." Other writers also imagined sudden, terrible air attacks in their books.

At the time, bombers had a small advantage over fighters. They had multiple engines and sleek, strong wings. So, to stop a bomber, fighters needed careful planning to get into the right position. Before World War II and the invention of radar, people used their eyes or ears to spot planes. This only gave a few minutes of warning. This was barely enough for World War I planes. But for 1930s planes, which flew much faster, it was not enough time. Bombs would be falling before fighters could get ready.

Because of this, Britain decided to focus on building many bombers. The idea was that having a strong bomber force would stop other countries from attacking them.

Before the war started in 1939, some experts predicted that hundreds of thousands of people would be hurt or killed by bombing. For example, one expert thought 250,000 people could die or be injured in Britain in the first week. People in 1938 thought of air war much like people today think of nuclear war.

However, a few people disagreed. One important person was Hugh Dowding, who led RAF Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain. Others included American Major Claire Chennault and Lieutenant Benjamin S. Kelsey. They argued that fighters could indeed shoot down bombers.

Bombing in Real Wars

Later studies of strategic bombing during World War II showed that Baldwin's statement was partly true. Bombers often did "get through," but at a high cost in lost planes and airmen.

During the Battle of Britain, fighters guided by radar were able to stop German daytime attacks. This forced the German air force (Luftwaffe) to switch to less accurate night bombing, known as The Blitz. Night fighters had a harder time, so the Blitz was mostly unopposed. But it did not break the spirit of the British people.

In August 1943, the US Army Air Forces sent 376 B-17 bombers to attack German cities. They had no long-range fighter escorts. They caused heavy damage to one target but lost 60 bombers. Many more were damaged, and 564 airmen were killed or captured. A second raid in October lost 77 bombers. Because of these heavy losses, unescorted daylight bombing deep into Germany was stopped until February 1944.

The Royal Air Force's Bomber Command lost 8,325 aircraft during the war. This was about 2.3% of planes lost per mission. But over Germany, the loss rate was much higher, sometimes over 5%. These losses were huge. However, new planes were built, and more airmen were trained. So, the bombing campaign grew throughout the war.

Studies after the war found that bombing alone did not make countries surrender. It did not cause the collapse that some had expected in Britain or Germany.

In the Pacific War, both Japan and the Allies used bombing effectively. Early in the war, Japanese planes from aircraft carriers destroyed or damaged US battleships in Hawaii. They also destroyed many US planes in Hawaii and the Philippine Islands. The US military did not use its single radar system in Hawaii well. Later, US bombers effectively destroyed many Japanese cities with regular or fire bombs. This happened before the use of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

"The bomber will not always get through"

After World War II, major countries built huge bombers to carry nuclear weapons. But by the 1960s, new technologies changed things. Better ground radar, guided missiles, radar-guided anti-aircraft guns, and faster fighter planes made it much harder for bombers to reach their targets.

A 1964 study looked at British V bombers. It guessed that a bomber without special defenses would face about six missiles. Each missile had a 75% chance of destroying its target. The study concluded that "the bomber will not always get through." It suggested that Britain should focus on Polaris submarine missiles instead. The United States Navy also started using Polaris submarines for similar reasons. They changed their aircraft carriers from carrying nuclear weapons to fighting regular wars.

The United States Air Force found it harder to change its large fleet of manned bombers to non-nuclear roles. They tried to redesign a high-speed bomber project to carry standoff missiles. But these missiles failed tests and the project was cancelled. A 1963 study stated that "long-range technical considerations... work against keeping the manned bomber."

See also

- Appeasement

- Carpet bombing

- Guilty Men

- Mutual assured destruction

- Schnellbomber

- Strategic bombing

- Roerich Pact

- Total war

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |