Victorian dress reform facts for kids

During the Victorian era (from the 1830s to 1900s), women's fashion was often uncomfortable and unhealthy. It included things like tight corsets, huge skirts, and heavy layers of clothing. The Victorian dress reform movement was a group of people, mostly women, who wanted to change this. They believed clothing should be more practical and comfortable. This movement is also known as the rational dress movement.

These reformers were often middle-class women who were also part of the first wave of feminism. This means they were fighting for women's rights, like the right to vote and get an education. They wanted women to be free from the strict rules of fashion. They also wanted clothes that covered the body properly and were "rational," meaning sensible.

The movement had its biggest success in changing women's undergarments. These could be changed without people noticing too much. Dress reformers also helped women wear simpler clothes for sports like bicycling or swimming. They also encouraged men to wear knitted wool union suits, which are like long underwear.

Some people in the movement even opened "dress reform parlors." These were shops where women could buy patterns or ready-made clothes that were more comfortable.

Contents

Why Tight Corsets Were a Problem

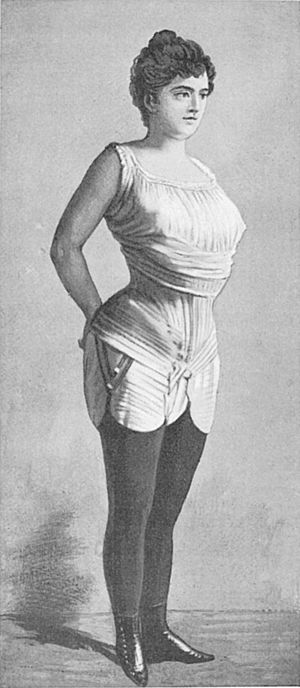

Fashion in the 1850s to 1880s meant wearing large crinolines (hoops under skirts), big bustles (pads at the back), and tiny waists. To get these tiny waists, women wore corsets that were tightly laced. This was called 'Tight-lacing'.

Dress reformers said that corsets were bad for health. They claimed corsets could damage organs, make it hard to have children, and cause weakness. But people who liked corsets said they were needed for a stylish look and were even enjoyable.

Doctors and journalists also spoke out against tight-lacing. They said it was vain and unhealthy. Reformers believed tight-lacing was a sign of moral indecency, meaning it wasn't proper.

American women who were fighting against slavery and for temperance (avoiding alcohol) also wanted sensible clothes. They needed to move freely for their public speaking and activism. Some reformers even thought that women's fashions were designed to keep women "subservient" or under control. They believed that changing clothes could change women's whole position in society, giving them more freedom, independence, and the ability to work.

Despite these protests, fashion didn't change much by 1900. The Edwardian Era still featured corsets that created an "S" shape, pushing the chest forward and hips back. Skirts were heavy, collars were high, and these clothes still made natural movement hard. They could also harm internal organs and affect a woman's ability to have children. The ideal woman in fashion magazines still had a very tiny, corseted waist.

Poor women sometimes used rope instead of steel or bone in their corsets to make working in fields easier.

Freedom Waists and Underwear Changes

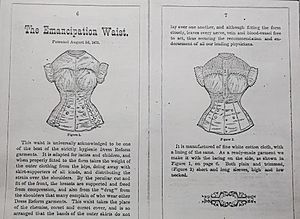

Dress reformers suggested the "emancipation waist" or liberty bodice to replace corsets. This was a tight, sleeveless vest that buttoned up the front. It had rows of buttons at the bottom to attach petticoats and skirts. This way, the weight of the skirts hung from the shoulders, not just the waist. This was much more comfortable. These bodices had to be custom-fitted by a dressmaker.

The "emancipation union under flannel" was first sold in America in 1868. It combined a shirt and leggings into one piece, known today as the union suit. It was first made for women but was also worn by men. People still wear union suits today as winter underwear.

In 1878, a German professor named Gustav Jaeger wrote a book saying that only clothes made of animal hair, like wool, were healthy. A British accountant, Lewis Tomalin, translated the book and opened a shop selling "Dr Jaeger's Sanitary Woollen System," which included wool union suits. These became very popular and were called "Jaegers."

Even with these new options, most women in the 19th and early 20th centuries still wore corsets every day. Photos, fashion magazines, and old clothes show this.

The Bloomer Suit

The most famous clothing item from the dress reform era was the bloomer suit. In 1851, a temperance activist named Elizabeth Smith Miller started wearing a more sensible outfit. It had loose trousers gathered at the ankles, like those worn by women in the Middle East, with a short dress or skirt and a vest over them.

She showed her new clothes to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, another activist, who liked them and started wearing them too. Then, Stanton visited Amelia Bloomer, who edited a temperance magazine called The Lily. Bloomer not only wore the costume but also promoted it in her magazine. Soon, more women wore this fashion, and they were called "Bloomers." The National Dress Reform Association, founded in 1856, supported this style.

However, the "Bloomers" faced a lot of teasing and harassment. People said women had "lost their mystery" by giving up their long, flowing dresses. Amelia Bloomer herself stopped wearing the outfit in 1859. She said that a new invention, the crinoline, was enough of a reform. The bloomer costume disappeared for a while but came back later in the 1890s as athletic wear for women, especially for bicycling.

Aesthetic Dress Movement

In the 1870s, a movement mostly in England, led by Mary Eliza Haweis, wanted dress reform to show off the body's natural shape. They preferred the looser styles from the medieval and renaissance times. This "aesthetic dress movement" criticized fashionable clothes for being stiff and unnatural. They wanted clothes that complemented the natural body.

Artists like the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood also disliked the fancy, stiff Victorian fashions with their tight corsets and hoops. They thought these styles were ugly and dishonest. Some women in this movement wore clothes inspired by romanticized medieval styles, with puffed juliette sleeves and long, trailing skirts. These clothes were made in soft colors from natural dyes, often with hand embroidery. They used silks, oriental designs, muted colors, and natural or frizzy hair, without a tight waist.

This "anti-fashion" style, called Artistic dress, spread in artistic groups in the 1860s. It faded in the 1870s but came back as Aesthetic dress in the 1880s. Writer Oscar Wilde and his wife Constance were big supporters, giving talks about it. In 1881, The Rational Dress Society was started in London. This group supported divided skirts as more practical. Lady Florence Harberton, the president, even wore a shorter skirt over wide trousers for cycling.

Dress Reform Around the World

The dress reform movement spread from the United States and Great Britain to countries in Northern Europe in the 1880s, and from Germany to Austria and the Netherlands. The topic was discussed internationally at the International Congress for Women's Work and Women's Endeavors in Berlin in 1896. Countries like Germany, America, England, and many others took part.

Germany

Germany was a leader in dress reform in the 19th century. It was part of a larger health movement called Lebensreform. This movement supported healthier clothing for both women and men, backed by doctors and scientists. They wanted women to be free from corsets and wear trousers.

The women's movement in Germany got involved after the International Women's Congress in Berlin in 1896. Two weeks later, the German dress reform association, Allgemeiner Verein zur Verbesserung der Frauenkleidung, was founded. They held their first exhibition in 1897. By 1899, there was even a permanent exhibition in Berlin showing "improved women's clothing." Like other countries, the German group focused on changing women's underwear, especially corsets. Their efforts were so successful that by 1907, the German corset industry was struggling because fewer women were using corsets.

Japan

Utako Shimoda (1854-1936) was a Japanese women's activist and educator. She felt that traditional kimonos were too restrictive. They stopped women and girls from moving freely and doing physical activities, which harmed their health. While Western clothes were becoming popular, she also thought corsets were bad for women's health.

Shimoda had worked for Empress Shōken. She changed the clothes worn by ladies-in-waiting at the Japanese imperial court to create a uniform for her Jissen Women's School. During the Meiji period (1868–1912) and Taishō period (1912–1926), other women's schools also started using the hakama (loose trousers). It became standard wear for high schools in Japan, though it was later mostly replaced with Western sailor-style uniforms.

Inokuchi Akuri also designed sports clothes for children. At the imperial court, simpler keiko outfits replaced more complicated garments.

Sweden

Sweden was a leading country in the dress reform movement in Northern Europe. The movement started there first and then spread to Denmark, Finland, and Norway.

In 1885, a professor named Curt Wallis brought an English dress reform book to Sweden. It was translated into Swedish. After a speech by Anne Charlotte Leffler, a reform costume was designed by Hanna Winge and made by Augusta Lundin. This was shown to the public and helped the movement. In 1886, the Swedish Dress Reform Society was founded.

After trying to launch a full reform costume, the Swedish movement focused on changing women's underwear, especially the corset. They worked with dress reform groups in Great Britain and America.

The dress reform movement had some success in Sweden. By the 1890s, corsets were no longer allowed for girls in Swedish schools. A leading Swedish fashion designer, Augusta Lundin, said that her clients no longer wore tight-lacing.

How Fashion Eventually Changed

Even though the Victorian dress reform movement didn't immediately change women's fashion everywhere, other social and political changes did. By the 1920s, clothing styles naturally became more relaxed.

New chances for women's college, the right to vote for women in 1920, and more job options for women during and after World War I all played a part. Fashion and underwear became looser as women gained more social standing. Women started wearing masculine-inspired clothes like simple skirt suits, ties, and stiff blouses. By the 1920s, male-style clothes for casual wear and sports were more accepted. New fashions needed lighter underwear, shorter skirts, looser tops, and trousers. They also praised slender, "boyish" figures. As Lady Duff Gordon said, in the 1920s, "women took off their corsets, reduced their clothing to the minimum tolerated by conventions and wore clothes which wrapped round them rather than fitted."

Even though corsets, girdles, and bras were still worn into the 1960s, women's freedom led to bigger changes in dress than the early feminists had even imagined.

Gallery

-

Approx. second half of 1880s poster showing Annie Oakley wearing short-skirted attire

-

An 1897 ad, showing a relatively early example of an ordinary non-sea-bathing woman in public view in unskirted garments (to ride a bicycle)

-

Wigan "pit brow lasses" scandalized by wearing trousers for dangerous work in coal mines. They wore skirts over their trousers, rolled up to the waist to keep them out of the way.

See also

- Bicycle

- Corset controversy

- History of the bicycle

- Lebensreform

- Liberty bodice

- Svenska drägtreformföreningen

- Trousers as women's clothing

- Victorian fashion

- Women's suffrage and Western women's fashion through the early 20th century

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |