W. Michael Blumenthal facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

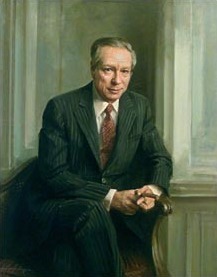

W. Michael Blumenthal

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 64th United States Secretary of the Treasury | |

| In office January 23, 1977 – August 4, 1979 |

|

| President | Jimmy Carter |

| Preceded by | William E. Simon |

| Succeeded by | G. William Miller |

| Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Economic and Business Affairs | |

| In office 1961–1967 |

|

| President | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Werner Michael Blumenthal

January 3, 1926 Oranienburg, Weimar Republic |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses | Margaret Polley (1951–1977) Barbara Bennett |

| Education |

|

| Signature | |

Werner Michael Blumenthal (born January 3, 1926) is a German-American business leader and economist. He was an important political adviser. From 1977 to 1979, he served as the United States Secretary of the Treasury for President Jimmy Carter.

When he was 13, Blumenthal and his Jewish family escaped Nazi Germany in 1939. They spent World War II in the Shanghai Ghetto in Japanese-occupied Shanghai, China. After the war, in 1947, he moved to San Francisco. He worked many different jobs to pay for his education. He earned degrees in international economics from the University of California, Berkeley and Princeton University.

Throughout his career, he worked in both business and government. Before joining President Carter's team, he was a successful business leader. He also held positions under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. As part of the Carter administration, he helped guide the country's economic plans. He also played a role in restarting connections with China. After leaving his government role, he became a top leader at companies like Burroughs Corporation and Unisys. Later, he spent 17 years as the director of the Jewish Museum in Berlin. He has written two books: The Invisible Wall (1998) and From Exile to Washington: A Memoir of Leadership in the Twentieth Century (2013). Michael Blumenthal is the oldest living former U.S. Cabinet member.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Michael Blumenthal was born in Oranienburg, which is in modern-day Germany. His parents were Rose Valerie and Ewald Blumenthal. His family owned a small dress shop. They had lived in Oranienburg since the 1500s.

In 1935, the Nazi party created the Nuremberg Laws. These laws made life very difficult for Jewish people. Blumenthal's family began to fear for their lives. They knew they had to leave Germany. He remembered Kristallnacht, a series of attacks against Jewish people and their property. These attacks started on November 9, 1938, when he was 12 years old.

I clearly remember ... when they came and smashed all the Jewish stores. I remember seeing the largest synagogue in Berlin burn, and I remember being beaten up by kids in uniform.

In 1938, Nazi Gestapo officers arrested his father without a reason. His father was taken to Buchenwald concentration camp. This was a large forced labor camp in Germany. His mother quickly sold their belongings. She managed to get her husband released. They had to sell their dress store for almost nothing. His older sister, Stefanie, remembered her mother's sadness. It was not just about the loss, but the unfairness of it.

With their little money, his mother bought tickets to Shanghai, China. Shanghai was an open port city that did not require a visa. They left Germany on a ship in 1939, just before World War II began. They could only take a few things and no money. He recalled the long journey. They stopped at many ports, but none would let Jewish refugees enter.

They hoped to stay in Shanghai only for a short time. They planned to travel to a safer country later. But World War II started, and Japan took control of Shanghai. The Blumenthals were forced to live in the Shanghai Ghetto. About 20,000 other Jewish refugees were also confined there for eight years.

Life in the Shanghai Ghetto

Blumenthal saw extreme poverty and hunger in the ghetto. He sometimes saw dead bodies in the streets. He described it as a "cesspool." He found a cleaning job at a chemical factory. He earned $1 a week, which helped feed his family.

I was confined to a faraway corner of Asia, so destitute that newspapers were stuffed into my shoes to cover up the holes ... I had no passport at all [and] for two and a half years I was a prisoner of the Japanese, and later not even the most junior American consular official would have given me the time of day.

His schooling was not regular. The stress of survival led to his parents' divorce. However, he learned English at a British school for a short time. He also learned some Chinese, French, and Portuguese.

When the war ended in 1945, American troops arrived in Shanghai. He got a job helping at a warehouse for the U.S. Air Force. His language skills were very helpful. By 1947, after much effort, he and his sister got visas to the U.S. They had been denied visas to Canada.

They traveled to San Francisco, where they knew no one. They had only $200 between them. Even with limited education and no country to call home, he worked hard to build a new life.

I came to this country feeling that I had capabilities and talents. I read a lot. I talked to people. I wanted to do things. I found out that I can cope reasonably well.

College and University Studies

Blumenthal's first full-time job was as a billing clerk. He earned $40 per week at the National Biscuit Company. Later, he enrolled at San Francisco City College. He supported himself with part-time jobs. These included truck driver, night elevator operator, busboy, and movie theater ticket-taker. He also worked as an armored guard and at a wax factory.

He was accepted into the University of California, Berkeley. He graduated with honors in 1951. He earned a Bachelor of Science degree in international economics. There, he met and married Margaret Eileen Polley in 1951. In 1952, Blumenthal became a U.S. citizen.

Blumenthal received a scholarship to Princeton University. He studied at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. He earned a Master of Arts and a Master of Public Affairs in 1953. In 1956, he received his Ph.D. in economics. His doctoral paper was about labor relations in the German steel industry. To earn money, his wife worked as a secretary. He taught economics at Princeton from 1954 to 1957. He also worked as a labor arbitrator for New Jersey.

Career Highlights

In 1957, Blumenthal left Princeton University to work at Crown Cork. This company made bottle caps. He stayed there until 1961 and became a vice president.

In 1961, he moved to Washington, D.C.. He was a registered Democrat. After John F. Kennedy became president, Blumenthal was offered a job. He became Kennedy's deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Economic and Business Affairs. He worked in the State Department from 1961 to 1967. He advised Kennedy on trade. After Kennedy's death, he advised Lyndon B. Johnson.

President Johnson made him a U.S. Ambassador. He was the chief U.S. negotiator at the Kennedy Round trade talks in Geneva. These talks were very important for global trade. Canada's Minister of Trade and Commerce called Blumenthal a tough negotiator. Blumenthal found this funny. He thought, "If they'd let me into the country in 1945, I might have been working on their side."

In 1967, Blumenthal left government work. He joined Bendix International, a company making auto parts, electronics, and aerospace items. After five years, he became its chairman and CEO. He stayed with Bendix for ten more years. When he first took over, Bendix was struggling. After five years as chairman, the company nearly doubled its sales. By 1976, Duns Review called Bendix "one of the five best-managed companies in the U.S."

Secretary of the Treasury

While Blumenthal was leading Bendix, newly elected President Carter chose him for a new role. He nominated Blumenthal to be his United States Secretary of the Treasury. He served in this position from January 23, 1977, to August 4, 1979. His nomination was approved by everyone. In June 1977, he went to a conference in Paris. The meeting focused on how Western countries would handle the slow economic recovery after a recession.

Blumenthal first met Carter in 1975 in Japan. Carter invited him to his home. He knew Blumenthal was a successful business manager and negotiator. Carter believed Blumenthal would offer good economic advice. Blumenthal noted that there were not many top Democratic businessmen. When he accepted the job, his income changed a lot. It went from $473,000 per year to $66,000. He was also amused to read a German newspaper headline. It said, "A Berliner is to Become Carter's New Minister of Finance."

As Secretary of the Treasury, he was not part of Carter's closest group of advisers. His duties were not always clear. He was the head of Carter's Economic Policy Group. He was also Carter's main economic policy official. But he could not fully set economic policy. He also had to share the role of chief economic spokesperson. This caused confusion and made his work less effective.

Blumenthal worked hard to fight inflation. Inflation is when prices go up and money buys less. It had risen from 7 percent in early 1978 to 11 percent by the fall. By summer 1979, inflation reached 14 percent. Unemployment in some cities was nearly 25 percent. Much of this increase was because OPEC raised oil prices. During this time, the U.S. dollar was also targeted by currency speculation. Countries like Germany and Japan saw their money become much stronger against the dollar.

In February 1979, Blumenthal visited China. He was the first American Cabinet officer to visit after the U.S. officially recognized China's Communist government. Before this, most American experts on China had never been there. His trip was so important that 20 journalists traveled with him. His experience living in Shanghai was a key reason Chinese leaders invited him. His trip was a great success. Blumenthal also returned the next month for the opening of the U.S. Embassy. He explained:

Our visit was an opening move in the slow, carefully managed, renewed coming together of China and the United States, haltingly begun with many fits and starts in the early seventies, and culminating nine years later with the reestablishment of full diplomatic relations (in which I would be destined to play an official role.)

He gave part of his speech in Chinese. He told Chinese leaders that America was worried about China's invasion of Vietnam. This had happened a week earlier. He asked them to withdraw their troops quickly. He warned that it could lead to "wider wars." The Chinese were very impressed by his speech. The Chinese army did withdraw a few weeks after his visit.

In July 1979, Carter announced his plans for the nation's economic and energy problems. At the same time, he asked five of his Cabinet members, including Blumenthal, to resign. Twenty-three other senior staff members also left.

Later Career

After resigning, he joined Burroughs Corporation in 1980. He became vice chairman, then chairman of the board a year later. In 1986, Burroughs merged with Sperry Corporation. The new company was called Unisys Corporation. Blumenthal became its chairman and chief executive officer (CEO). He stayed with Unisys until 1990. After several years of losses, he stepped down. He then became a partner at Lazard Freres & Company, an investment bank. With more free time, he taught economics at Princeton.

In April 2016, he was one of eight former Treasury secretaries. They asked the United Kingdom to stay in the European Union. This was before the June 2016 vote on leaving the EU.

Jewish Museum Berlin

In 1997, Blumenthal became the first director of the Jewish Museum Berlin in Germany. He started his work in December of that year. He accepted an invitation from the city of Berlin. The first Jewish Museum in Berlin was founded in 1933. But the Nazi government closed it in 1938. The new museum shows 2,000 years of German-Jewish history. This includes the sad events of The Holocaust. It is the largest Jewish museum in Europe.

Blumenthal was the museum's director from 1997 until 2014. The museum opened in 2001, thanks to his leadership. This project gained a lot of attention in Germany and worldwide. In 1999 and 2006, Blumenthal received Germany's Senior Medals of Merit. These awards recognized his work for Germany in Berlin.

Personal Life

He married Margaret Eileen Polley, a teacher, while in college. They had three daughters: Ann, Jill, and Jane.

He now lives in Princeton, New Jersey. He is with his second wife, Barbara (née Bennett). They have one son, Michael.

In 2008, he was chosen as a delegate for the 2008 Democratic National Convention. He supported then-Senator Barack Obama.

Blumenthal is featured in the 2020 documentary Harbor from the Holocaust.

Awards and Honors

- He received The International Center in New York's Award of Excellence.

- In 1980, Blumenthal received the Horatio Alger Award. This is from the Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans.

- In 1999, he received the Leo Baeck Medal. This was for his work promoting tolerance and social justice. He also received the Grand Cross of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany.

- In 2002, he received the Goethe Medal, Culture Prize of Berlin, and Berlin's Medal of Merit.

- In 2013, he received the Lucius D. Clay Medal and Roland Berger Prize for Human Dignity.

- In 2014, he received the Nachama Prize for Tolerance and Civil Courage.

- In 2015, he received the Jewish Museum Berlin's Prize for Tolerance and Understanding.

- He was made an honorary citizen of Berlin in 2015. He also became an honorary citizen of Oranienburg, his birthplace.

- Blumenthal has many honorary degrees from major U.S. universities.

- In 1979, he received Princeton University's Madison Medal for Outstanding Public Service.

See also

- List of foreign-born United States Cabinet members

- List of Jewish United States Cabinet members