Wardrobe of Mary, Queen of Scots facts for kids

Mary, Queen of Scots, had a very detailed wardrobe! Many records tell us about the clothes she wore. These records include lists of her clothing and jewelry, and even notes from her tailors.

Contents

A Queen's Amazing Wardrobe

Mary, Queen of Scots (born 1542, died 1587), spent her childhood and teenage years in France from 1548 to 1560. We know a lot about the clothes bought for her, especially in 1551. Her wedding dress in 1558 was also described in great detail.

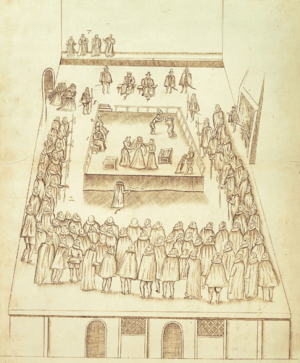

When she returned to Scotland, even more records of her clothes were kept. Her royal treasurer's accounts and her wardrobe manager, Servais de Condé, wrote down everything. Lists of her clothing and jewelry were made while she was in Scotland and after she went to England. Even what she wore on the day she was executed at Fotheringhay Castle in 1587 was widely reported!

We don't know much about Mary's baby clothes in Scotland. But we do know that someone named Margaret Balcomie had soap and coal to warm water for washing Mary's linen. In France in 1551, her clothes were very fancy. A white satin skirt and sleeves had 120 diamonds and rubies sewn onto them! Her hairnets, called coifs, had gold buttons or rubies. Her tailor, Nicolas du Moncel, did all this beautiful sewing.

Dancing and Masques in France

Mary wore farthingales, which were hoops that made her skirts stand out. She loved to dance in masques, which were special performances where people wore costumes. She danced with her French governess, Françoise d'Humières. Their costumes were made from light silver and gold fabrics, decorated with shiny silver and gold metallic spangles. These were like sequins, called papillotes in French. In 1554, Mary even played a character called the Delphic Sibyl in a masque.

In 1554, her governess, Françoise d'Estainville, asked Mary's mother if she could buy two diamonds. These were to make one of Mary's headbands, which already had rubies and pearls, longer. She also wanted to buy a new dress made of cloth of gold for Mary. This was for a wedding at Fontainebleau. Mary's new outfit was meant to look like the fashionable clothes worn by the French princesses. Mary also mentioned in a letter to her mother that some embroidered sleeves were being made for her in Scotland.

Mary's Look on Coins

Some of Mary's Scottish coins were designed by John Acheson, who visited the French court in 1553. Gold coins called ryals show her from the side. She wears a hairnet, or caul, with two jeweled bands. These bands appear in her jewelry lists and were called bordures in French. One band, the bordure de touret, went across her forehead, and a longer one, the bordure d'oriellette, went over her head.

Mourning Clothes: White and Black

After her first husband, Francis II of France, died in 1560, Mary wore a special type of mourning called deuil blanc, or "white mourning." This included a white pleated cambric veil. A famous drawing of her in this outfit was made by François Clouet. The paintings made later show her in a dark blue or green dress, which wasn't in the original drawing.

In September 1561, tailors made black mourning cloaks and skirts for Mary and her 15 ladies. They wore these for her official entry into Edinburgh. Mary wore black Florence serge, which was a type of fabric. The other costumes were made from a cheaper black fabric.

In November 1561, the royal records mention the women of her household getting a "second mourning" outfit. This might mean they received more black velvet mourning clothes. In December 1561, Mary remembered her husband's death anniversary. The English ambassador, Thomas Randolph, noticed that the Scottish nobles at court did not wear mourning clothes that day. One mourning outfit, called a "dule weid," had a large veil and seven pieces of "black crisp of silk."

Mary even wore mourning clothes when she married Lord Darnley on July 29, 1565. She entered the chapel wearing a "great mourning gown of black" with a "great wide mourning hood." Randolph said it looked like what she wore at her first husband's funeral. After the wedding, she changed into her new wedding costume.

When Lord Darnley died in February 1567, Mary needed 24 papers of pins for her new mourning clothes! The fabric was black serge of Florence, with some black plaid. Her skirt and sleeves were silk chamlet, lined with taffeta. Her headdresses were made of linen and camerage (cambric).

Clothes in the Queen's Records

During Mary's time as queen in Scotland, records of fabric purchases and payments to tailors are found in the Lord Treasurer's accounts. Mary had a special department in her household just for her wardrobe. It had officers and skilled workers like tailors and embroiderers. There were also "tapissiers" who took care of tapestries, beds, and furniture.

Servais de Condé, one of her valets, kept a written record in French of how the more expensive fabrics were used. For example, in July 1564, black velvet was given to Mary's tailor, Jean de Compiègne, to make a purse for handkerchiefs.

Some linen items in her lists might have been handkerchiefs, while others were head coverings. Other linen items included pairs of callesons or caleçons, which were linen hose, stockings, or undergarments.

Lists of Mary's clothes, written in French, still exist today. For example, one list from 1562 describes a skirt that was given to her favorite, Mary Beaton. Mary had 15 embroidered skirts and six plain ones. She also had 15 skirts made of cloth of gold or silver. A cloth of gold skirt with matching sleeves was given to Magdalen Livingstone for her wedding.

Mary wore her skirts over a shaped farthingale, which was stiffened with "girds" made of whale baleen. In December 1563, her tailor Jacques de Senlis changed an old black velvet skirt that belonged to Mary's mother into a new style for the queen.

The records also mention velvet collars for the queen's little dogs, called "les petitz chiens de la Royne"! The old Scottish and French words in Mary's clothing lists can be hard to understand. But sometimes, comparing the French and Scottish entries for the same item helps us understand what they meant.

Notes in the lists also show gifts of clothing that Mary gave to her favorite nobles, courtiers, and women in her household. She even gave a skirt to the "little daughter of her laundress," Margaret Douchall.

Special Costumes and Masques

Mary wore her crown and special robes for important state events, like the first day of the Parliament of Scotland on May 26, 1563. Her robes were described as a "rob ryall of purper velvot embroiderit about with gold," meaning a royal robe of purple velvet embroidered with gold. It was also lined with spotted ermine fur.

Mary's Highland Clothes

Mary and her court sometimes wore Highland clothes when they visited places like Argyll and Inverness in the north of Scotland. In June 1563, the court prepared "Hyeland apparell" for a trip to Argyll. Mary wore a "marvellous fair" costume that was a gift from Agnes Campbell.

A French writer named Brantôme said he saw Mary in Highland costume. He claimed she looked like a goddess because her beauty made the costume look amazing. Sadly, if such a portrait ever existed, it's gone now.

Woolen tartan or plaid fabric was bought in Inverness. These cloths might not have looked exactly like modern tartan fabrics. Some "Highland" items appear in her lists, like three Highland mantles in black, blue, and white. These might have been for her travels or for masque costumes. Among Mary's shirts, called "sarks," were four English blackwork shirts and a "hieland syd sark of yallow lyning pasmentit with purpour silk and silver."

Masques and Disguises

Costumes were made for dancers and lute players who performed for Mary and her court. For a wedding at Castle Campbell on January 10, 1563, they dressed as shepherds in white taffeta with purses made of white damask.

In December 1563, a masque involved three large blue velvet Swiss hats and wigs. There was also a blue velvet hat for Nichola the Fool. Mary's tailor made costumes from orange "changing" or shot taffeta for a masque in February 1565 at Holyrood Palace. A smaller costume in the same fabric was made for a young girl at court.

Mary and her ladies sometimes wore men's clothes for dancing and for "guising," which meant masked visits and walks in Scottish towns. On Easter Monday in April 1565, Mary and her ladies dressed like "bourgeois wives," meaning ordinary townswomen. They walked up and down the steep streets of Stirling, collecting money for a banquet. This shows that the clothes worn by ladies at court were very different from what ordinary women wore in towns.

In the days after her marriage in July 1565, Mary and Darnley walked up and down Edinburgh High Street in disguise. For a masque to entertain the French ambassador, her tailor made six costumes decorated with flames. These flames were made from cloth of gold reused from old cushion covers! During this masque, the queen's ladies, "cled in men's apperrell" (dressed in men's clothing), gave 8 Scottish daggers to the French guests. The daggers had black velvet scabbards embroidered with gold.

Mary went to Alloa Tower about a month after her son, Prince James, was born. It is said she danced around the Market Cross of Stirling in "homely sort," meaning in simple clothes.

In January 1567, Mary's tailor was given clothes, including a black "Almain" or German-style cloak. In February, the jester George Styne had a costume made of blue kersey fabric.

On the night Lord Darnley was killed by an explosion, Mary attended a wedding party and masque for her servant Bastian Pagez. Mary gave the bride satin, velvet, and green ribbons for her dress. Darnley's father later said that some witnesses claimed Mary was dressed in men's clothing that night. He said she often liked to wear men's clothes for secret dances with her husband and for masked walks through the streets at night.

Mary in Conflict

When Mary was at Inverness Castle in September 1562, she saw the armed guards returning at night. She said she wished she "was not a man to know what life it was to lie all night in the fields, or to walk upon the causeway with a jack and a knapschall (helmet), a Glasgow buckler, and a broad sword." She wished she could experience being a soldier.

Reports say that Mary wore male clothing on her ride from Borthwick Castle to Dunbar Castle in 1567. Some even say she was disguised as a page. The next day, before the battle of Carberry Hill, Mary wore a short red petticoat that reached her knees at Dunbar.

An English official, William Drury, heard another description of Mary's costume at this time. He said she was dressed at Dunbar "after the attire and fashion of the women of Edinburgh." This included a red petticoat tied with points, a partlet (worn over the shoulders), a velvet hat, and a muffler. Both male clothing and ordinary townswomen's clothes were part of Mary's costumes for masques and disguises.

Life in Prison: Lochleven and England

Even in prison at Lochleven Castle, Mary received clothes and sewing thread for embroidery. Her tailor usually sent her silk thread for sewing and crochet. In July 1567, she asked for an embroiderer to draw patterns for her. She also asked for silk thread, gold and silver sewing thread, black and white satin doublets and skirts, a red doublet, a taffeta loose gown, and clothes for her maids. Mary also wanted cambric and linen, and two pairs of sheets with black thread for embroidery, needles, and a cushion for lace-making.

Mary tried to escape from Lochleven disguised in her laundress's clothes. But the boatmen on Loch Leven recognized her and brought her back. She finally escaped from Lochleven on May 2, 1568. Her disguise involved a borrowed red dress and changing her hairstyle to look like a local woman.

When Mary arrived in England, her clothes were "very mean," meaning simple, and she had no change of clothes. She wrote to Queen Elizabeth, saying she hadn't changed her clothes since her escape because she had been traveling by night.

Carlisle Castle

At Carlisle Castle, Francis Knollys was very impressed by the hairdressing skills of Mary Seton. Mary said Mary Seton was the "finest busker, the finest dresser of a woman's head and hair that is to be seen in any country." Knollys wrote that Mary Seton put a "curled hair" (a wig) on the Queen that looked very delicate. He said Mary Seton had a new way of dressing hair almost every day, without much cost, and it made a woman look very good.

Mary received some black clothes by June 28, 1568. Knollys sent to Edinburgh for more of Mary's clothes because "she seemeth to esteem not of any apparyll other than hyr owne" (she didn't like any clothes other than her own). The first clothes sent from Lochleven Castle were not enough. Mary complained that in three chests, there was only one taffeta gown, and the rest were just cloaks, saddle cloths, sleeves, partlets, and hairnets.

Queen Elizabeth sent Mary 16 yards of black velvet, 16 yards of black satin, and 10 yards of black taffeta. This gift was seen by some as a hint that Mary should be in mourning clothes.

Mary received her portable alarm clock or chiming watch from Lochleven. It was kept in a purse of silver and grey lace work, which she might have made herself. She also set up an old cloth of estate (a canopy used above a throne) from Scotland above her chair at Bolton Castle. This was her way of showing her royal status.

Tutbury Castle

In January 1569, furniture and tapestries were sent to Tutbury Castle for Mary. This included tapestries, bedcovers, bedding, and chairs covered in rich fabrics. Mary arrived at Tutbury on February 4, 1569. Her French tailor, Jacques Senlis, and the tapestry worker and embroiderer, Florian, rejoined her household.

The Earl of Shrewsbury described Mary at Tutbury in March 1569. He said she was working on embroidery and making designs with Bess of Hardwick, Lady Livingstone, and Mary Seton. This was a peaceful activity. The embroidery pieces they made together are known as the Oxburgh Hangings. In a letter from September 1570, Mary mentioned that her servant Bastian Pagez designed embroidery patterns to cheer her up.

There were rumors that Mary would try to escape from prison in April 1571. One plan was for her to pretend to be sick while dancing. When she was carried to bed, a friend in her clothes would take her place. Mary would then escape, dressed as a man, and ride away. Another plan was for her to slip away during a hunt, leaving a friend dressed in her riding clothes. Again, Mary would change into male clothing and ride away. A third plan was for the queen to cut her hair and smear her face with dirt, like a "turnbroche" (a boy who turned a spit over the kitchen fire). But Mary never tried to escape using these methods.

Mary had clothes sent to her from France. In November 1572, she wrote to the French ambassador, hoping he could ask her mother-in-law, Catherine de' Medici, to buy linen for herself and her ladies. A shopping list from 1572, made by her tailor, gives an idea of the clothes and fabrics she got from Paris. The order included ready-made velvet Spanish-style gowns, stockings, shoes, slippers, and embroidered handkerchiefs. These purchases were packed in two chests and shipped to the French ambassador in London to be sent to Mary at Sheffield Castle.

Sheffield and French Clothes

In January 1576, the French ambassador asked Queen Elizabeth to allow four trunks of French-made clothes to be delivered to Mary at Sheffield Manor. Mary made a will (a legal document about her wishes) when she was at Sheffield Manor in February 1577. She wanted her large bed of "cramoysi brun" (dark crimson) embroidered velvet to be used for her funeral.

While at Sheffield in 1581, the French ambassador's wife sent Mary a gown. Mary's tailor, Jacques de Senlis, had died, and she wanted to hire Jean de Compiegne, who had worked for her in Scotland. She was able to buy silk fabrics for her clothes in France using money from her French income.

Secret Messages

Mary found a clever way to send secret messages. She suggested writing sometimes on white taffeta fabric or a fine linen called "linomple." The ambassador would mention the length of the cloth in his letters, saying it was a certain number of yards or ells plus one half. This would tell her that he had written on the cloth with invisible ink made with alum.

Gifts for Queen Elizabeth

Mary hoped to gain Queen Elizabeth's favor by giving her gifts. Handmade items were highly valued, especially if they were made from the finest materials. In 1574, Mary embroidered a crimson satin skirt with silver thread. She had sent the ambassador a sample of the silk she needed. She soon wrote for more crimson silk thread, thinner silver thread, and crimson taffeta for the lining. The ambassador presented the finished skirt to Elizabeth, saying it was a sign of friendship. He reported that the gift was a success.

Mary also planned to make more gifts for Elizabeth, including a "coiffure with the suite" (a headdress with matching accessories) and some lacework. She asked the ambassador for advice on what Elizabeth would like best. She also asked him to send gold braids and silver spangles, which she called papillottes.

In July 1576, Mary gave Elizabeth a skirt front, made in her household. She followed up with an embroidered box and a headdress. She wrote that if Elizabeth liked the skirt, she could have others made, even more beautiful. Mary even asked Elizabeth if she would send the pattern of the high-necked top she wore, so Mary could copy it!

Mary also provided clothes for some of the women in her household. In 1584, Mary asked the French ambassador in London to take special care of her secret letters and pay the messengers well. He should pretend the money was for gold and silver embroidery thread he sent to her.

Mary's Clothes in Edinburgh Castle, 1578

While Mary was in England, and her son James VI was growing up, many of Mary's clothes and palace furnishings were locked up in Edinburgh Castle. A list was made in March 1578, written in the old Scottish language. It included her "gownes, vaskenis, skirtis, slevis, doublettis, vaillis, vardingallis, cloikis" (gowns, bodices, skirts, sleeves, doublets, veils, farthingales, cloaks).

Among the hundreds of items were a "Highland kirtle of black stemming embroidered with blue silk." This was related to a black gown found in Mary's chest. There were also white canvas shepherd's kirtles, which were left over from a masque performed at Castle Campbell in 1563. The castle also held costumes from court parties, including feathers, golden shields, silver headdresses, and "Egyptian" hats made of red and yellow fabrics.

Accessories included "huidis, quaiffis, collaris, rabattis, orilyeitis (fronts of hoods), napkins, caming cloths, covers of night gear, hose, shoes, and gloves." At least 36 pairs of her velvet shoes remained in Edinburgh Castle, "of sundry colours passmented with gold and silver." These were probably made for her by Fremyn Alezard, a shoemaker.

There were also sixty pieces of canvas marked for embroidery, including a bed valance that was "drawin upoun paper and begun to sew." Some unfinished embroidery pieces had the arms of the House of Longueville and had belonged to Mary's mother, Mary of Guise.

Dolls and Mary's Cabinet

In one chest stored in Edinburgh Castle, there was a set of dolls called "pippens" with their tiny wardrobes of farthingales, sleeves, and slippers. These dolls might have been for play, or they could have been used as fashion dolls. They might have helped spread new clothing patterns for Mary and her ladies. In 1565, a writer noted that princesses and queens sent each other dolls to show details of foreign clothing.

The dolls were listed with other interesting items that seemed to be from Mary's cabinet of curiosities. A special "cabinet room" at Holyrood Palace was made for Mary in September 1561. Its walls were lined with a fabric called "Paris green."

Mary's Final Days: Execution Clothes

Before Mary's execution, her secretaries and her wardrobe master, Jérôme Pasquier, were questioned. Pasquier's job included buying cloth in London for the household's uniforms.

Adam Blackwood wrote about Mary's execution and her clothing. He said her veil, which reached the ground, was one she usually wore for important events. Another account describes her costume as she left her bedroom: she wore a wig, and on her head, she had a dressing of lawn fabric with lace edges. She had a perfume holder chain and a religious medal around her neck, a crucifix in her hand, and a rosary at her belt with a golden cross.

Her gown was black satin with a long train and long sleeves. It had jet and pearl buttons. Over a pair of purple velvet sleeves, she had short black satin sleeves. Her underskirt was figured black satin, and her petticoat skirt was crimson velvet. Her shoes were Spanish leather, and she wore green silk garters. Her lower stockings were sky blue wool, decorated with silver, and next to her leg, she wore white Jersey hose.

The two executioners helped her take off her clothes, with her two women assisting. She put the crucifix on a stool. One executioner took the religious medal from her neck, and she held onto it, saying she wanted to give it to one of her women. Then they took off her perfume chain and all her other clothes. She put on a pair of sleeves herself. Finally, she was dressed only in her petticoat and underskirt. Anything touched by the queen's blood was burned in the fireplace.

An English soldier heard that one of the executioners found a little dog under her clothes while untying her garters!

Mary had mentioned in a letter in 1577 that she had been sent rosaries and a religious medal from Rome. These might be the items mentioned in the execution story. Some historians believe Mary wore red under her black clothes to show she was a martyr. Red petticoats were common back then, and some doctors even thought red clothes were good for health.

A glove at Saffron Walden Museum is said to have been a gift from Mary to Marmaduke Darrell, an English administrator of her household. The leather glove is embroidered with colored silks and silver thread and lined with crimson satin.

See also

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |