William Jacob Knox Jr. facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Jacob Knox Jr.

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | January 5, 1904 |

| Died | July 9, 1995 (aged 91) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Harvard University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

| Institutions | Columbia University, Manhattan Project |

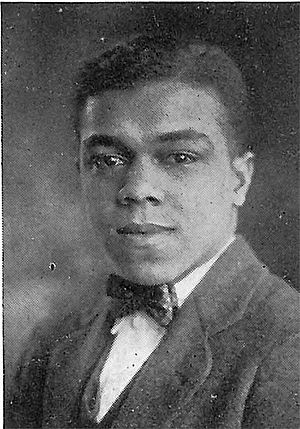

William Jacob Knox Jr. (January 5, 1904 – July 9, 1995) was an important American chemist. He worked at Columbia University in New York City and was one of the African-American scientists and technicians on the Manhattan Project. He held a very special role as the only African American supervisor for the Manhattan Project. Knox helped develop ways to separate parts of uranium, which was used to create the first atomic weapons.

Knox was highly educated, earning his first degree from Harvard University. He then continued his studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). By 1935, his family was quite unique, with 7% of all African Americans holding a Ph.D. being from the Knox family. After World War II, Knox worked at the Eastman Kodak Company. He was known as the expert for solving problems with coatings. Later in his life, Knox became involved in fighting for civil rights and helping his community.

Contents

Early Life and Education

William Jacob Knox Jr. was born on January 5, 1904, in New Bedford, Massachusetts. His father, William Knox, worked for the US postal service, and his mother was Estella Briggs. William's family had a history of overcoming challenges. His grandfather, Elijah Knox, bought his freedom from slavery in 1846. One of his grandmothers was Harriet Jacobs, who wrote a famous book about her experiences called Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. The Knox family believed strongly in getting a good education.

William was the oldest of five children. He and his two younger brothers, Clinton Everett and Lawrence “Larry” Howland, all went to Harvard University and other colleges. All three brothers earned doctoral degrees. William and Lawrence studied chemistry, while Clinton studied history. William started at Harvard in 1921 and finished in 1925. During his time there, he faced unfair treatment because of his race. For example, he was told to leave his room in the freshman dorms because they were only for white students. Despite these difficulties, William Knox chose to get even more education.

In 1929, Knox began teaching at Howard University in Washington, D.C. While teaching there, he met Edna Lenora Jordan. They got married on September 1, 1931, and had one child, Sandra Knox.

Early Career

After earning his master's degree in organic chemistry in 1929 and his Ph.D. in chemical engineering in 1935 from MIT, Knox became a professor. He taught chemistry at North Carolina A&T College from 1935 to 1942. He taught different types of chemistry, including general, organic, and physical chemistry. In 1942, Knox was promoted and became the head of the chemistry department at Talladega College. This college is a historically black institution in Talladega, Alabama.

The Manhattan Project

In 1943, Knox joined a team of scientists at Columbia University in New York City. This team was part of the Manhattan Project, which lasted from 1942 to 1945. The Manhattan Project was a secret research effort to develop the first atomic weapons. It involved teams at Columbia University and special sites in places like Hanford, Washington, Los Alamos, New Mexico, and Oak Ridge, Tennessee. William's brother Lawrence also joined him at Columbia University, working as a head research analyst for the project.

The project was successful. The United States developed the first atomic weapons, which helped bring an end to World War II. Knox's team focused on finding ways to separate uranium isotopes using a method called gaseous diffusion. Columbia University received the government's first contract to explore using atomic power for energy and weapons. Experiments there showed that uranium could be used to create an explosion much more powerful than anything known before.

Knox held a very important position: he was the only African American scientist to be a supervisor in the Manhattan Project. Like many scientists involved, Knox and his team did not fully know how important their research was. Their work on breaking apart uranium isotopes, especially using uranium hexafluoride, was key to creating the atomic bombs used in 1945. These weapons used Uranium-235 and plutonium-239. Knox was a section leader in the Corrosion Section before leaving Columbia University when the war ended.

After the War

Working at Eastman Kodak Company

In 1945, after World War II ended, Knox left his job with the nuclear research team at Columbia University. He soon became a research assistant at Eastman Kodak Company (Kodak) in Rochester, New York. He worked there from 1945 to 1970. He was only the second African American chemist with a Ph.D. to be hired by the company. At that time, Kodak was a world leader in photographic technology. Knox used his scientific skills to help the company. He was given credit for 21 patents during his time at Kodak. These patents were about using special chemicals in the photographic process. Even after he retired and passed away, Kodak continued to use nine of his original patents. These patents help make photographic coatings stronger and protect pictures.

Teaching Again

After leaving Kodak, William Knox returned to North Carolina A&T University to teach chemistry again. He then fully retired in 1973.

Death

William Jacob Knox Jr. passed away on July 9, 1995, at the age of 91. He died in Newton, Massachusetts, after battling prostate cancer.

Impact and Legacy

Knox deeply cared about his community and worked for social justice. He had faced unfair treatment throughout his life and was an active member of his local chapter of the NAACP. When Knox was looking for a home near his daughter's school, he faced difficulties. A coworker helped him by buying a piece of land and then selling it to Knox. This experience motivated Knox to fight against unfair housing practices and for basic civil rights.

Knox was also a founding member of the Urban League of Rochester. This organization was started in 1965 to help African Americans, Latinos, and other disadvantaged people gain financial independence and equal rights. The Urban League of Rochester offers many programs to help people who are struggling. It also provides scholarships to minority students, and Knox was a donor to these scholarships. Today, the Urban League of Rochester helps over 4,000 people. By being a founding member, Knox showed that he not only fought against unfairness but also worked hard to make his community better.

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |