Witchcraft in early modern Britain facts for kids

During the early modern period in Britain, from the 1500s to the late 1700s, many people believed in witchcraft. This led to a time when many people were accused of being witches and faced trials.

In this article, "witchcraft" means any magical or supernatural things people were thought to do. At first, before 1542, some magical practices were seen as helpful, like healing. People who did this were called the cunning folk. But later, people started to believe witchcraft came from the Devil. This led to new laws and many trials.

Contents

What People Believed About Witches

People in Britain have believed in magic and magical practices for a very long time, even before the 1500s. They thought some people could influence nature or predict the future.

How Witches Were Thought to Practice Magic

People thought there were many kinds of witchcraft. Some included alchemy, which was trying to change substances like lead into gold. Another was astrology, which was reading the stars to guess the future. But during the early modern period, people worried most about magic that involved the Devil.

They believed witches made deals with the Devil to get special powers. In Scotland, especially, people focused on this idea of a "demonic pact." Witches were no longer seen as healers. Instead, people believed they caused many problems, like sick farm animals, strange diseases, and bad weather.

The first woman found guilty of witchcraft in Ireland, Lady Alice Kyteler, was accused of things like animal sacrifice and making potions to control others. She was also said to have a familiar, which was an animal companion like a cat or dog. People thought a spirit lived in the animal and helped the witch with her magic.

How Many People Believed

It wasn't just everyday people who believed in witches. Kings, Queens, and even the Church believed too. When King Henry VIII changed the main religion in Britain, some thought it opened the door for dark forces. Because of this, a law was passed to define what a witch was and how they should be punished.

However, not everyone was convinced. A man named Reginald Scot in England wrote a book called The Discoverie of Witchcraft. In it, he said that people in Britain were tricked into believing in witchcraft by simple illusions. His book became popular, but not because of his doubts about magic. It also had details about what witches were thought to do, like sections on alchemy and spirits. Many think this book inspired Shakespeare's witches in his play Macbeth.

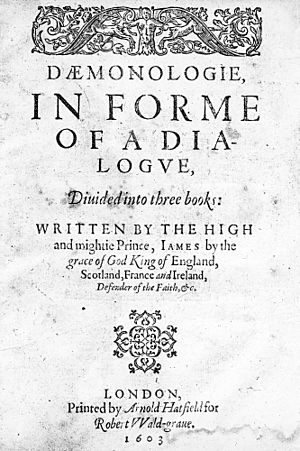

Another book that might have influenced Macbeth was Daemonologie by King James VI of Scotland. Unlike Scot, King James VI strongly believed in magic and demons. His book talked about dark magic and how demons could trick people into doing evil. He published it to tell people in Scotland why witches needed to be hunted and punished.

Witch Hunts and Trials

Wales

Compared to other parts of Britain, Wales had fewer witch trials during this time. Many people were accused, but it was hard to find enough proof to convict them. The first witch tried and put to death in Wales was Gwen ferch Ellis. She was accused of using a poppet (a small doll used in spells) and a harmful charm. Charms were common for healing, which Gwen also did. But her charm was written backward, which people believed meant it was for harm.

Scotland

Between 1500 and 1700, about 4,000 to 6,000 people were tried for witchcraft in Scotland. This was much more than in England or Wales. This might be because King James VI was very interested in magic. He even watched trials and torture of women accused of witchcraft. After Scotland joined England in 1707, witch trials became less common because new laws controlled them more strictly.

One of Scotland's most famous mass witch trials happened under King James VI. These trials took place in North Berwick from 1590 to 1592. At least 70 accused witches were tortured and, in most cases, killed. The trials began after the King faced terrible storms while sailing to Denmark to marry Princess Anne. King James VI had seen authorities in Denmark blame women like Anna Kolding for storms during the Copenhagen witch trials. So, he blamed the "witches" in North Berwick for his bad journey. Most of what we know about the North Berwick witch trials comes from the King's book Daemonologie and a pamphlet called Newes from Scotland. These trials were very famous and influenced Shakespeare's Macbeth.

England

Fewer people were killed for witchcraft in England than in Scotland. However, many important trials still happened because of people who called themselves "witch-hunters." One famous witch-hunter was Matthew Hopkins from East Anglia. He called himself the "Witchfinder General." Hopkins and his helpers were believed to have caused the deaths of at least 300 accused men and women.

One well-known trial was that of the Witches of Belvoir. This involved three women: Joan Flowers and her two daughters, Margaret and Philippa Flowers. They were known locally for using herbs to heal. After they were fired from working at Belvoir Castle, the Earl and two of his sons died. The Countess and her daughter also became very sick. Five years later, the Flowers were arrested. Joan Flowers died on her way to trial. Her daughters said they had familiars and saw demons. They also confessed to casting a spell on the Earl and Countess's children.

The last known executions of witches in England happened during the Bideford witch trial in Devon. Three women were hanged for making a local woman, Grace Thomas, sick through magic. There were other accusations too, but no real proof. The women who were hanged were Temperance Lloyd, a widow; Mary Trembles, a beggar; and Susanna Edwards, another beggar.

Ireland

Unlike the large number of trials and executions in other parts of Britain and Europe, Ireland had very few. Some people think this is because there was less religious conflict in Ireland at the time. Others suggest it's because Irish culture strongly believed in the Sidhe, or fairies. Fairies were often blamed for problems like milk spoiling or crops dying, which in other countries was linked to witchcraft.

Still, some notable trials happened. The first was Lady Alice Kyteler (mentioned above) and her maidservant Petronilla de Meath. Petronilla was tortured until she confessed that both were witches. This led to them being burned at the stake. Another well-known trial happened in March 1711. Eight women were found guilty and sentenced to death for witchcraft in the Islandmagee witch trial on Islandmagee. This area had strong Scottish-English roots, which some historians believe might explain why this trial was larger than others in Ireland.

Theories About Witchcraft Beliefs

The Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age was a time of big climate change around the early modern period. In Britain, it brought cold, rainy weather and growing glaciers. This weather caused serious problems. Crops failed, farm animals didn't produce enough, and people got sick. Back then, people didn't understand climate change. So, many historians, like Wolfgang Behringer, believe that people blamed witchcraft for these unexplained problems. Older women from poorer families were often the easiest to blame. They had little power to defend themselves and often became victims of witch accusations.

Religion

The Church and the government didn't officially recognize witchcraft until the early 1500s. This was a time of great religious conflict in Britain, known as the European wars of religion. Many historians think these two events are connected.

Some historians, like Peter Leeson and Jacob Russ, suggest that witch hunts increased because the Protestant and Catholic churches were competing for followers. They say that both churches wanted more people to join them. This might explain why Ireland had so few witch trials. Ireland remained mostly Catholic even after the Reformation.

Politics

In his book Witchcraft, Witch-Hunting, and politics in early modern England, Peter Elmer argues that many major witch trials in England happened when political leaders felt their power was threatened. For example, no trials happened in Dorchester from 1629 to 1637. Elmer suggests this was because the government there felt strong and secure.

Another idea, from American sociologist Albert James Bergesen, is that witch hunts were a tool used by governments. He believes they used witch hunts to bring communities together. By giving people a common enemy (witches), the government could then show they were strong by getting rid of that enemy. This made people trust their leaders more.

See also

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |