Early modern Britain facts for kids

Early modern Britain is the story of the island of Great Britain during the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. This exciting time saw many big changes! There were lots of wars, especially with France. Important events included the English Renaissance (a time of new ideas in art and learning), the English Reformation and Scottish Reformation (when the church changed), the English Civil War, the return of King Charles II, the Glorious Revolution, the Treaty of Union (which joined England and Scotland), and the rise and fall of the First British Empire.

Contents

England During the Tudor Period (1485–1603)

The English Renaissance: A Time of New Ideas

The "English Renaissance" was a period in the 16th and 17th centuries when England saw a burst of creativity. It was inspired by the Italian Renaissance. During this time, English music, especially the madrigal, became very popular. Drama also thrived with famous writers like William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, and Ben Jonson. Epic poems, like Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene, were also written.

Some historians debate if this period truly connects to the Italian Renaissance artists like Leonardo da Vinci or Michelangelo. However, most agree that there was a huge artistic growth in England under the Tudor kings and queens. This led to the amazing works of Shakespeare and his friends.

The Powerful Tudor Rulers

Many experts say that Early Modern Britain began in 1485. This was when Henry Tudor won the battle of Bosworth Field and became king, ending the Wars of the Roses. His reign brought peace and stability to England, allowing art and business to grow. England wouldn't see another major war on its own soil until the English Civil War in the 1600s.

During this time, Henry VII and his son Henry VIII made the English monarchy much stronger. Kings were gaining more power across Europe, partly because of new inventions like gunpowder. Henry VIII also used the Protestant Reformation to take power from the Roman Catholic Church. He took over the monasteries' land and declared himself the head of the new Anglican Church. Under the Tudors, the government became more organized, run by educated officials.

The idea that kings had a "divine right" to rule also became popular. This meant they believed God chose them to be king. James I strongly believed in this idea.

As the power of the old noble families decreased, the power of business people grew. Trade became very important, and money played a big role in how the government worked. This new class of wealthy merchants gained a lot of influence. However, their power wasn't fully reflected in the government structure. This led to a long struggle in the 17th century between the king and Parliament.

The Golden Elizabethan Era (1558–1603)

The Elizabethan Era was the time when Queen Elizabeth I ruled (1558–1603). It's often called a golden age in English history. This was the peak of the English Renaissance, with amazing achievements in English literature and poetry. Elizabethan theatre was famous, and William Shakespeare wrote many of his plays during this time. It was also an age of exploration and expansion overseas. At home, the Protestant Reformation became firmly established.

The Elizabethan Age is seen as a special time because it was peaceful compared to the periods before and after. It was a break from the religious conflicts between Protestants and Catholics. It also came before the big fights between Parliament and the monarchy in the 17th century. Queen Elizabeth helped settle the religious divide with the Elizabethan Religious Settlement. Parliament wasn't yet strong enough to challenge the queen's power.

England was also doing well compared to other European countries. The Italian Renaissance had ended due to foreign control. France was busy with its own religious wars. Because England had been pushed out of its last lands in Europe, the long-standing conflict with France mostly paused during Elizabeth's reign.

England's main rival was Spain. They clashed in Europe and the Americas, leading to the Anglo-Spanish War of 1585–1604. This war was fought across two continents (Europe and the Americas) and two oceans (the Atlantic and Pacific).

During this time, England had a strong, organized, and effective government. This was thanks to the changes made by Henry VII and Henry VIII. Economically, England started to benefit greatly from new trade routes across the Atlantic Ocean.

Scotland from the 15th Century to 1603

Scotland made great progress in education during the 15th century. New universities were founded: the University of St Andrews in 1413, the University of Glasgow in 1450, and the University of Aberdeen in 1495. The Education Act 1496 also helped improve learning.

In 1468, Scotland gained its last major territory. King James III married Margaret of Denmark, and received the Orkney Islands and the Shetland Islands as part of her dowry.

After James III died in 1488, his son James IV became king. He successfully brought the Western Isles under royal control, ending the independent rule of the Lord of the Isles. In 1503, he married Henry VII's daughter, Margaret Tudor. This marriage set the stage for the Union of the Crowns later on. James IV's reign is often seen as a time of cultural growth, and the European Renaissance began to influence Scotland. James IV was the last Scottish king known to speak Gaelic.

In 1512, a treaty with France meant that Scottish and French citizens became citizens of each other's countries. However, a year later, this alliance led to trouble. James IV had to invade England to support France, which was being attacked by Henry VIII. The invasion ended badly at the battle of Flodden Field. The King, many nobles, and over 10,000 soldiers were killed. This disaster affected all of Scotland, and the government was once again run by regents (people who rule for a young king).

When James V finally escaped from his regents in 1528, he worked to control the Highlands and Islands, just like his father had. He married the French noblewoman Marie de Guise. His reign was successful until another war with England led to defeat at the battle of Solway Moss in 1542. James died shortly after. The day before his death, he learned he had a daughter, who would become Mary, Queen of Scots. Scotland was again ruled by a regent, James Hamilton.

Mary, Queen of Scots

Within two years, Henry VIII tried to force a marriage between Mary and his son, Edward. This was called the Rough Wooing. There were border fights, and in May 1544, a large English army burned Edinburgh. In 1547, after Henry VIII died, English forces won the Battle of Pinkie and occupied Haddington.

Mary was sent to France at age five to marry the French heir. Her mother, Mary of Guise, stayed in Scotland to protect Mary's and France's interests. Mary returned to Scotland after her husband, Francis II of France, died.

Mary lost control of Scotland after seven years. She was imprisoned in Lochleven Castle and forced to give up her throne. She escaped and tried to regain power by force. After her defeat at the Battle of Langside in 1568, she fled to England. She left her young son, James VI, with regents. In England, she became a focus for Catholic plots and was eventually executed by her cousin, Elizabeth I.

The Scottish Reformation

During the 16th century, Scotland experienced a Protestant Reformation. The ideas of Martin Luther and then John Calvin began to spread. The execution of Protestant preachers, like Patrick Hamilton in 1528 and George Wishart in 1546, only made these ideas stronger.

The Scottish Church's Reformation followed a short civil war in 1559–60. English help on the Protestant side was key. A Reformed confession of faith was adopted by Parliament in 1560, while the young Mary, Queen of Scots, was still in France. The most important figure was John Knox, who followed both John Calvin and George Wishart. Roman Catholicism didn't disappear completely, especially in parts of the Highlands.

The Reformation was a bit uncertain during Queen Mary's reign, as she was Catholic but allowed Protestantism. After she was removed from power in 1567, her infant son James VI was raised as a Protestant. In 1603, after Queen Elizabeth I died without children, the English crown passed to James. He became James I of England and James VI of Scotland, uniting the two countries under his personal rule. This was the first political link between the two independent nations, hinting at the future union of Scotland and England in 1707.

Early Stuart Era: 1603–1660

The Union of the Crowns

The Union of the Crowns happened when James VI, King of Scots, also became King James I of England. This meant one man ruled two separate kingdoms, each with its own government. The two countries remained distinct until the Acts of Union in 1707. Within hours of Elizabeth's death, James was declared king in London, and the news was met with no problems.

The Jacobean era refers to the years of James I's reign in England, from 1603 to 1625. It followed the Elizabethan era and came before the Caroline era. This period is known for its unique style in architecture, art, and literature.

The Caroline era refers to the years of King Charles I's rule over both countries, from 1625 to 1642. This period was followed by the English Civil War (1642–1651) and the English Interregnum (1651–1660), when there was no king.

The English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of conflicts between Parliament's supporters (called Roundheads) and the King's supporters (called Cavaliers). These fights happened between 1642 and 1651. The first (1642–1646) and second (1648–1649) wars were between King Charles I's followers and the Long Parliament's supporters. The third war (1649–1651) was fought between supporters of King Charles II and the Rump Parliament. The Civil War ended when Parliament won the Battle of Worcester on September 3, 1651.

The Diggers were a group started by Gerrard Winstanley in 1649. They tried to change society by living a simple farming life in small, equal communities. They were one of many Protestant groups that appeared around this time.

The English Interregnum was the period of rule by Parliament and the military in England and Wales after the English Civil War. It began with the execution of Charles I in 1649 and ended with the return of Charles II in 1660.

The Protectorate (1653–1660)

The Civil War led to the trial and execution of Charles I. His son, Charles II, went into exile. The English monarchy was replaced first by the Commonwealth of England (1649–1653) and then by a Protectorate (1653–1659), led by Oliver Cromwell. After Cromwell died, his son took over, but he was a weak ruler with little support. The military and religious groups who had supported Cromwell began to argue among themselves.

Later Stuart Era: 1660–1714

The Restoration (1660–1688)

In 1660, the remaining members of the Long Parliament (1640–1660) decided to end the chaos after Cromwell's death. Many people wanted the monarchy to return under the Stuarts. There was a strong desire for the old royal traditions. General George Monck, who had supported Cromwell, led the effort to bring back the king. Charles II, who was in exile in Holland, paid close attention. He issued the Declaration of Breda, promising forgiveness and saying he would let Parliament decide things. Parliament invited Charles to return, and he landed in Dover with great excitement on May 26, 1660.

The new Parliament, called the Cavalier Parliament, passed the Clarendon Code. This was designed to strengthen the Church of England. Only true members of the Church could hold public office. A major issue was trade competition with the Dutch, which led to the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–67). The only good outcome was gaining New Netherland, which became New York.

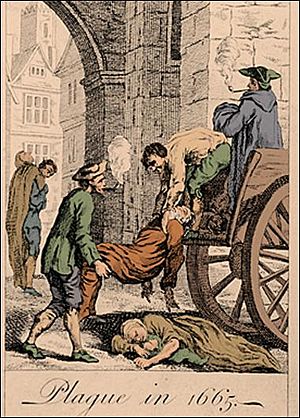

During the war with the Dutch, the Great Plague of London hit in 1665–66. At its worst, 1,000 people died each day in London. On top of that, the Great Fire of London burned down the main business areas of London. It destroyed 13,000 buildings, but few lives were lost.

In 1670, King Charles made a secret alliance with his cousin, King Louis XIV of France. Louis agreed to help Charles in the Third Anglo-Dutch War and pay him money. Charles secretly promised to become Catholic later. Charles tried to allow religious freedom for Catholics and non-Anglican Protestants with his 1672 Royal Declaration of Indulgence. However, Parliament forced him to withdraw it.

In 1679, Titus Oates claimed there was a "Popish Plot" to kill the king. This led to the Exclusion Crisis when it was revealed that Charles's brother and heir, James, Duke of York, was Catholic. The question was whether to prevent James from becoming king. This crisis created the first political parties: the Whigs wanted to exclude James, while the Tories supported James and believed it was wrong to interfere with the rightful succession. After a plot to murder Charles and James was discovered in 1683, some Whig leaders were executed or exiled. Charles dissolved Parliament in 1681 and ruled alone until his death on February 6, 1685.

The Glorious Revolution (1688–89)

When Charles II died in 1685, his brother became King James II. He ruled with the support of the Tory party. He tried to introduce unpopular ideas that would bring Catholicism back to England. The Monmouth Rebellion broke out but was brutally put down. Many important people turned against the king. In late 1688, they invited William III and Mary II to rule.

James went into exile in France, where King Louis XIV supported his claim to the English throne. In England, the Jacobites (supporters of James) also upheld his claims. They were a military threat for the next 50 years. William III ruled from 1689 to 1702, and his wife Queen Mary II was co-ruler until her death in 1694. The Glorious Revolution set an important rule: British monarchs could not rule without Parliament's agreement. This was confirmed by the English Bill of Rights and the Hanoverian succession.

Anglo-Dutch Wars

The Anglo-Dutch Wars were three wars between England and the Dutch from 1652 to 1674. They were caused by political arguments and competition in shipping. Religion wasn't a factor, as both sides were Protestant. In the first war (1652–54), the British navy had an advantage with more powerful "ships of the line." The British also captured many Dutch merchant ships.

In the second war (1665–67), the Dutch navy won some battles. This war cost London much more than planned, and the king asked for peace in 1667 with the Treaty of Breda. It ended the fights over "mercantilism" (using force to protect and expand national trade). Meanwhile, the French were building navies that threatened both the Netherlands and Great Britain. In the third war (1672–74), the British allied with France, but the Dutch outsmarted both. King Charles II ran out of money and political support. The Dutch controlled sea trade routes until 1713. The British gained the thriving colony of New Netherland, which they renamed New York.

The 18th Century

The 18th century was a time of many major wars, especially with France. It saw the growth and fall of the First British Empire, the start of the Second British Empire, and steady economic growth at home.

Peace between England and the Netherlands in 1688 meant they became allies in the Nine Years' War. This war, fought in Europe and overseas, made England a stronger colonial power than the Dutch. The Dutch had to spend more money on land wars in Europe. The 18th century would see England (after 1707, Great Britain) become the world's leading colonial power, with France as its main rival.

In 1701, England, Portugal, and the Netherlands joined the Holy Roman Empire against Spain and France in the War of the Spanish Succession. This conflict, which France and Spain lost, lasted until 1714. The British Empire gained more land: Newfoundland and Acadia from France, and Gibraltar and Menorca from Spain. Gibraltar, still a British overseas territory today, became a vital naval base. It allowed Britain to control the Atlantic entrance and exit to the Mediterranean Sea.

The Treaty of Union

The united Kingdom of Great Britain was formed on May 1, 1707. This happened after the parliaments of Scotland and England approved the Treaty of Union of 1706. This combined the two parliaments and royal titles. Queen Anne (who already ruled both England and Scotland) wanted closer political ties. Under her guidance, a Treaty of Union was created, and talks between England and Scotland began in 1706.

Scottish supporters of the union believed that if they didn't agree, the union would be forced on them with worse terms. There were months of fierce debates in both capitals and across both kingdoms. In Scotland, the debate sometimes turned into public disorder. Many Scottish people were against the idea of a union. However, Scotland couldn't continue on its own for long. After the financially disastrous Darien Scheme, the nearly bankrupt Parliament of Scotland reluctantly accepted the proposals.

The Acts of Union took effect in 1707, joining the separate Parliaments and crowns of England and Scotland. This formed the single Kingdom of Great Britain. Queen Anne became the first ruler of the unified British throne. Scotland sent 45 Members to join the existing Members from the English Parliament in the new House of Commons of Great Britain. They also sent 16 representative peers to join the existing peers in the new House of Lords.

Jacobite Risings

Keeping the royal family secure was important in Britain, just like in other countries. The House of Stuart had lost the throne when King James II (1633–1701) fled to France in 1688. However, he and his son, the "Old Pretender", claimed to be the rightful kings. They had support from some groups in England and from King Louis XIV in France. The main issue was religion; the Stuarts had Catholic support, while the Whigs in Britain strongly opposed Catholicism. Most Tories did not publicly support the Jacobites, though some quietly did.

After King William III (1702) and Queen Anne (1714) died, the throne went to the Protestant House of Hanover, starting with King George I in 1714. They were Germans and not very popular in Britain. The island nation was only vulnerable to an invasion by sea, which the Jacobites planned. The main attempts were the Jacobite rising of 1715 and the Jacobite rising of 1745. Both failed to gain much public support. The Jacobite defeat at the Battle of Culloden in 1746 ended any real hope of a Stuart king returning. Historian Basil Williams said, "there was never any serious danger to the dynasty."

Overseas Trade and Wealth

This era was very prosperous as business people expanded their trade around the world. By the 1720s, Britain was one of the wealthiest countries. Daniel Defoe proudly wrote that Britain was "the most diligent nation in the world."

While other major powers focused on gaining land and protecting their royal families, Britain had different goals. Its main aim was to build a worldwide trading network for its merchants, manufacturers, shippers, and bankers. This needed a very powerful Royal Navy so no rival could stop its ships or invade Britain. The government helped private businesses by creating many London-based companies. These companies set up trading posts and started import-export businesses globally. Each was given a monopoly (exclusive right) to trade in a specific region. The first was the Muscovy Company in 1555, which traded with Russia. Other important companies included the East India Company and the Hudson's Bay Company in Canada.

The Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa was set up in 1662 to trade in gold, ivory, and slaves. It was reestablished as the Royal African Company in 1672 and focused on the slave trade. British involvement in the triangular slave trade brought huge profits. Even losing the 13 American colonies was balanced by a good trading relationship with the new United States. Britain became dominant in trade with India and largely controlled the very profitable slave, sugar, and commercial trades from West Africa and the West Indies. China was next on their list. Other countries also set up similar monopolies, but on a smaller scale. Only the Netherlands focused on trade as much as England. British exports soared from £6.5 million in 1700 to £43.2 million in 1800.

There was one big financial disaster called the South Sea Bubble. The South Sea Company was a private business that was supposed to trade with South America. But its real purpose was to reorganize old government loans through market manipulation and speculation. It issued stock four times in 1720, reaching about 8,000 investors. Prices kept rising, from £130 a share to £1,000, making huge paper profits for those in the know. The Bubble burst overnight, ruining many investors. Investigations showed that bribes had reached high places, even the king.

The Slave Trade

An important outcome of the Peace of Utrecht was Britain's increased role in the slave trade. A key secret agreement with France gave Britain a 30-year monopoly on the Spanish slave trade, known as the Asiento de Negros. Queen Anne also allowed colonies like Virginia to make laws that promoted black slavery. She boasted to Parliament about taking the Asiento from France, and London celebrated this economic success. Most of the slave trade involved sales to Spanish colonies in the Caribbean and Mexico, as well as to British colonies in the Caribbean and North America.

Historian Vinita Ricks notes that Queen Anne received "22.5% (and King Philip V of Spain 28%) of all profits collected for her personal fortune." Ricks concludes that the Queen's "connection to slave trade revenue meant that she was no longer a neutral observer. She had a vested interest in what happened on slave ships." Besides sales to Spanish colonies, Britain had its own sugar islands in the Caribbean, like Jamaica, Barbados, Nevis, and Antigua. These islands provided steady profits from the sugar produced by enslaved labor.

Warfare and Money

From 1700 to 1850, Britain was involved in 137 wars or rebellions. Apart from losing the American War of Independence, it was generally successful in warfare. Britain was especially good at paying for its military efforts. France and Spain, in contrast, went bankrupt. Britain kept a relatively large and expensive Royal Navy, but a small standing army. When more soldiers were needed, Britain hired mercenaries or paid allies to provide armies.

The rising costs of war forced a change in how the government got money. It shifted from income from royal lands and special taxes to relying on customs and excise taxes. After 1790, an income tax was introduced. Working with bankers in London, the government raised large loans during wartime and paid them back in peacetime. Taxes rose to 20% of national income, but the economy also grew. The demand for war supplies boosted industries like naval supplies, weapons, and textiles. This gave Britain an advantage in international trade after the wars.

The British Empire Grows

The Seven Years' War, which began in 1756, was the first war fought on a global scale. It took place in Europe, India, North America, the Caribbean, the Philippines, and Africa. The signing of the Treaty of Paris (1763) had big effects for Britain and its empire. In North America, France's role as a colonial power ended when it gave New France to Britain and Louisiana to Spain. Spain gave Florida to Britain. In India, the Carnatic War left France with its small territories but with military limits. This effectively left India's future to Britain. The British victory over France in the Seven Years' War made Britain the world's leading colonial power.

During the 1760s and 1770s, relations between the Thirteen Colonies and Britain became tense. This was mainly because American colonists resented the British Parliament taxing them without their consent. Disagreement turned to violence, and in 1775, the American War of Independence began. The next year, the colonists declared the independence of the United States. With help from France, they won the war in 1783. The Treaties of Versailles also ended wars with the French and Spanish. The Fourth Anglo-Dutch War ended the following year.

Historians see the loss of the United States, then Britain's most populated colony, as the shift between the "first" and "second" empires. Britain turned its attention away from the Americas to Asia, the Pacific, and later Africa. Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, argued that colonies were not essential. He said that free trade should replace the old mercantilist policies (which protected trade). The growth of trade between the newly independent United States and Britain after 1783 showed that political control wasn't needed for economic success.

For its first century, the British East India Company focused on trade, not building an empire in India. But during the 18th century, as the Mughal Empire weakened, the Company started focusing on territory. It also struggled with its French rival, La Compagnie française des Indes orientales, during the Carnatic Wars of the 1740s and 1750s. The Battle of Plassey, where the British led by Robert Clive defeated the French and their Indian allies, gave the Company control of Bengal. It became a major military and political power in India. In the following decades, it slowly increased the size of its controlled territories. It ruled directly or indirectly through local rulers, using the threat of force from the Indian Army. 80% of this army was made up of native Indian sepoys.

In 1770, James Cook was the first European to visit the eastern coast of Australia during a scientific voyage to the South Pacific. In 1778, Joseph Banks, Cook's botanist, told the government that Botany Bay was suitable for a penal settlement (a place to send prisoners). In 1787, the first ship of convicts sailed, arriving in 1788.

At the start of the 19th century, Britain faced a new challenge from France under Napoleon. This struggle was different from past wars; it was a battle of ideas between the two nations. Napoleon threatened to invade Britain itself, which would mean a similar fate to the countries his armies had taken over in Europe. So, Britain spent a lot of money and resources to win the Napoleonic Wars. The Royal Navy blockaded French ports and won a decisive victory over the French fleet at Trafalgar in 1805.

How State Power Grew

Recently, historians have looked deeper into how state power grew during this period. They especially study the long 18th century, from about 1660 to 1837. One idea, by Oliver MacDonagh, describes a growing and centralized government. Another idea, by Edward Higgs, sees the state as a collector of information. He looks at local records, the census, and even topics like spies and surveillance. John Brewer showed how powerful and centralized the 'fiscal-military' state was in the 18th century. Finally, many studies explore the state as an idea that people feel loyal to.

Images for kids

See also

- British colonisation of the Americas

- Caroline era, 1625–1642

- Company rule in India

- Early Modern English literature

- Early modern period

- Elizabethan era, 1558–1603

- English Civil War, 1642–1651

- Evolution of the British Empire

- History of Scotland

- Historiography of the United Kingdom

- Historiography of the British Empire

- International relations 1648–1814

- English Interregnum, 1651–1660

- Jacobean era, 1603–1627 in England, 1567–1625 in Scotland

- Witchcraft in early modern Britain

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |