Wolves in Great Britain facts for kids

Wolves once lived all over Great Britain. Old writings from Roman and Saxon times say that there were tons of wolves on the island. Unlike other animals in Britain, wolves here grew very big. Some bones show they might have been as large as Arctic wolves!

Sadly, wolves disappeared from Britain. This happened because forests were cut down, and people hunted them a lot, often for money rewards (called bounties).

Contents

Wolves in the Past and Why They Disappeared

England and Wales

Some historians say that around the year 950, King Athelstan made the Welsh King Hywel Dda give him 300 wolf skins every year. Other stories say King Athelstan asked for gold, and it was his nephew, Edgar the Peaceful, who later asked for wolf skins from the Welsh king. Back then, many wolves lived in the thick forests near Wales.

This rule about wolf skins continued until the Normans took over England. Sometimes, criminals were told to bring a certain number of wolf tongues instead of being punished with death. A monk named Galfrid wrote that wolves were so common in Northumbria that even rich sheep owners couldn't protect their sheep, even with many workers.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (an old history book) says that January was called "Wolf monath" (Wolf month). This was because it was the first full month when important people would hunt wolves. The hunting season ended in March. This was when wolves had their babies, making them easier to catch, and their fur was best.

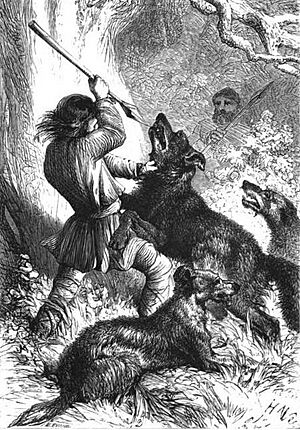

The Norman kings (who ruled from 1066 to 1154) hired people just to hunt wolves. Many people were given land if they promised to hunt wolves. For example, William the Conqueror gave land in Northumberland to Robert de Umfraville. Robert had to protect the land from enemies and wolves. People could hunt wolves freely, except in royal hunting areas. This was because the kings didn't want common people to hunt deer there.

English wolves were often caught in traps more than hunted. The Wolfhunt family, who lived in Peak forest in the 1200s, would go into the forest in March and December. They would put sticky tar (pitch) in places where wolves often went. At that time of year, wolves had trouble smelling the pitch. In dry summers, they would go into the forest to destroy wolf cubs.

King John paid 10 shillings for every two wolves caught. King Edward I, who ruled from 1272 to 1307, wanted all wolves in his kingdom to be wiped out. He hired a man named Peter Corbet to destroy wolves in areas like Gloucestershire and Shropshire. These areas were near Wales, where wolves were more common.

Later, in the 1300s, a man named Thomas Engaine was given land if he found special hunting dogs to kill wolves in several counties. In the 1400s, Sir Robert Plumpton held land in Nottingham. His job was to blow a horn and chase wolves in Sherwood Forest.

Most people think wolves became extinct in England during the time of King Henry VII (1485–1509), or at least became very rare. By then, wolves were only found in a few wild forests like Blackburnshire and Bowland in Lancashire, and parts of Derbyshire and Yorkshire. Even into the early 1800s, people in East Riding of Yorkshire still offered money for killing wolves.

Scotland

In Scotland, during the time of King James VI, wolves were such a danger to travelers that special houses called spittals were built along roads for protection.

In Sutherland, wolves dug up graves so often that people in Eddrachillis started burying their dead on the island of Handa.

- On Ederachillis’ shore

- The grey wolf lies in wait-

- Woe to the broken door,

- Woe to the loosened gate,

- And the groping wretch whom sleety fogs

- On the trackless moor belate.

- The lean and hungry wolf,

- With his fangs so sharp and white,

- His starveling body pinched

- By the frost of a northern night,

- And his pitiless eyes that scare the dark

- With their green and threatening light.

- […]

- He climeth the guarding dyke,

- He leapeth the hurdle bars,

- He steals the sheep from the pen,

- And the fish from the boat-house spars,

- And he digs the dead from out of the sod,

- And gnaws them under the stars.

- […]

- Thus every grave we dug

- The hungry wolf uptore,

- And every morn the sod

- Was strewn with bones and gore:

- Our mother-earth had denied us rest

- On Ederchaillis’ shore

—The Book of Highland Minstrelsy, 1846

Burying people on islands also happened on Tanera Mòr and Inishail. In Atholl, coffins were made wolf-proof by building them from five flat stones. Wolves likely disappeared from the Scottish Lowlands between the 1200s and 1400s, when huge areas of forest were cut down.

King James I made a law in 1427. It said there had to be three wolf hunts a year between April 25 and August 1. This was when wolves were having their cubs. Scottish wolf numbers were highest in the second half of the 1500s. Mary, Queen of Scots even hunted wolves in the forest of Atholl in 1563.

Later, wolves caused so much damage to cattle in Sutherland that in 1577, King James VI made wolf hunting three times a year mandatory. Stories about the killing of Scotland's last wolf are different. Official records say the last Scottish wolf was killed by Sir Ewen Cameron in 1680 in Killiecrankie. But some reports say wolves lived in Scotland until the 1700s, and one story even says a wolf was seen as late as 1888.

Wolves in Stories and Legends

In the Welsh story of Gelert, Llywelyn the Great, a prince, killed his loyal dog Gelert. He found the dog covered in blood and thought it had hurt his baby son. But later, he found his son safe. The blood was from a wolf that Gelert had killed to protect the baby prince. In Welsh myths, two characters, St. Ciwa and Bairre, were said to have been raised by wolves.

Scottish folklore tells of an old man in Morayshire named MacQueen of Findhorn. He is said to have killed the very last wolf in 1743.

Old Wolf Bones Found

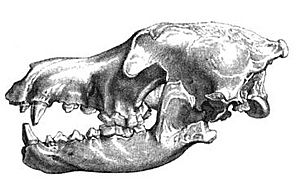

Scientists have found wolf bones in different caves. In Kirkdale Cave, there were not many wolf bones compared to cave hyena bones. Some teeth first thought to be from wolves turned out to be from young hyenas. The few real wolf bones found there were probably carried into the cave by hyenas to eat.

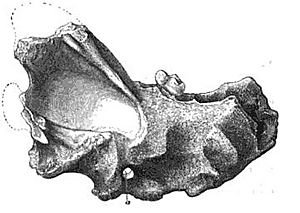

In some caves in Plymouth, a Mr. Whidbey found several bones and teeth that looked just like those of modern wolves. A scientist named Richard Owen looked at a jaw bone from Oreston. He noticed it was from a young wolf and showed signs of injury, maybe from a fight with another wolf.

An almost complete wolf skull was found in Kents Cavern. It was the same size as an Arctic wolf skull. Scientists knew it was a wolf because of its low forehead.

Should Wolves Come Back to Scotland and England?

In 1999, a professor named Dr. Martyn Gorman suggested bringing wolves back to the Scottish Highlands and English countryside. He thought they could help control the huge number of red deer. These deer were eating young trees in forests. Scottish National Heritage thought about bringing wolves back, but sheep farmers were very upset, so the idea was put on hold.

In 2002, Paul van Vlissingen, a rich landowner in Scotland, also suggested bringing back wolves and lynxes. He said that current ways of controlling deer weren't working. He also thought wolves would bring more tourists to Scotland.

In 2007, researchers from Britain and Norway said that bringing wolves back would help plants and birds grow better. This is because deer eat many plants, stopping them from growing. Their study also looked at what people thought about bringing wolves back. Most people were positive. People in the countryside were more careful, but they were open to the idea if they would get paid for any livestock lost to wolves.

Richard Morley, from the Wolves and Humans Foundation, predicted in 2007 that more people would support bringing wolves back. He said that while wolves would be good for tourism, farmers had serious worries about their sheep. These worries needed to be understood.

Bringing wolves and other large meat-eating animals back to the Scottish Highlands is still a big debate. However, some people are already making plans. Paul Lister, who owns the Alladale Estate in Scotland, wants to bring wolves, lynx, and bears back to his wildlife reserve. Many arguments against this are about how it might affect farming. But Lister says there's not much farming in his area, so it wouldn't be a problem.

Bringing wolves back could help the economy and nature, just like it did in the U.S. In 1995, wolves were brought back to Yellowstone National Park. This changed the area's nature, helping forests grow again and increasing the number of different animals. Tourism related to wolves also brings millions of dollars to Wyoming every year.

|

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |