Women's suffrage in Hawaii facts for kids

The fight for women's suffrage in Hawaii began in the 1890s. Suffrage means the right to vote. When the Hawaiian Kingdom was in charge, women had important roles in the government. Some women could even vote in the House of Nobles.

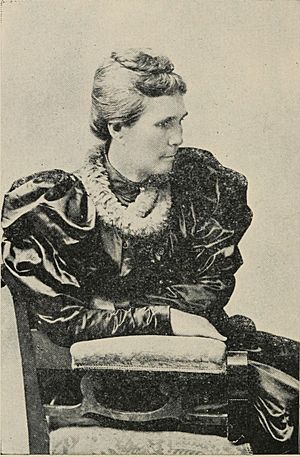

However, after Queen Liliʻuokalani was overthrown in 1893, women's roles became more limited. Two important leaders, Wilhelmine Kekelaokalaninui Widemann Dowsett and Emma Kaili Metcalf Beckley Nakuina, immediately started working for women's voting rights. The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in Hawaii also supported women's suffrage in 1894.

When Hawaii became a U.S. territory in 1899, some people had unfair ideas about Native Hawaiians being able to govern themselves. This caused problems for women's voting rights. The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) asked the United States Congress to let women in Hawaii vote, but it didn't happen right away.

Work for women's suffrage picked up in 1912 when Carrie Chapman Catt visited Hawaii. That year, Dowsett started the National Women's Equal Suffrage Association of Hawai'i. Catt promised to help this group as a representative for NAWSA. From 1915 to 1916, Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole asked the U.S. Congress to grant women's suffrage for Hawaii. Even though many hoped for success, it didn't pass.

In 1919, women who supported suffrage held large demonstrations across Hawaii. They wanted the local government to pass bills for women's voting rights. These were some of the biggest protests for suffrage in Hawaii, but the bills still didn't pass. Finally, women in Hawaii gained the right to vote when the Nineteenth Amendment was passed for the entire United States.

How did women's voting rights change in Hawaii?

Before Hawaii became part of the United States in 1898, the Hawaiian Kingdom gave women important roles. Women from the `aliʻi` (noble) class had a lot of political power. For example, the `Kuhina Nui` (premier) was a co-ruler position, often held by a female relative of the king. High-ranking chiefesses served as island governors. They could vote and make laws in the House of Nobles. The 1840 Constitution listed four women as members of the House of Nobles.

The 1840 constitution did not clearly stop common women from voting. It used the Hawaiian word `makaʻāinana`, which means the general population and doesn't specify gender. However, historians are not sure if common women actually voted during this time. From 1840 to 1850, common people could vote for members of the House of Representatives (who were all men). But after 1850, voting was limited to male citizens. Later Hawaiian constitutions, starting in 1852, only allowed men to vote.

Queen Liliʻuokalani became queen in 1891. She worked to bring back more power to the monarchy. Women like judge Emma Kaili Metcalf Beckley Nakuina held important government jobs under Queen Liliʻuokalani. But in 1893, a coup overthrew her rule. A new provisional government took over Hawaii.

The provisional government stopped women from voting. In 1894, a group called the Woman Suffrage Committee of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) tried to convince Hawaii's leaders to let women vote. But their idea was rejected. One reason was that it would increase the number of Native Hawaiians who could vote. Another idea was to make voters own property, which would also limit who could vote.

Hawaii became a U.S. territory in July 1898. The Organic Act of 1900 then set up a territorial governor.

What were the efforts for women's voting rights?

In 1890, during King Kalākaua's rule, Representatives William Pūnohu White and John Bush tried to change the constitution to allow women to vote. This effort did not succeed. Two years later, during Queen Liliʻuokalani's reign, Representative Joseph Nāwahī introduced another bill for women's suffrage. If these efforts had worked, Hawaii would have been the first nation to grant women the right to vote, even before New Zealand in 1893. Nāwahī and White also advised Queen Liliʻuokalani.

White women in the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) wanted to bring women's suffrage to Hawaii in the 1890s. Mary Tenney Castle was part of this WCTU suffrage work. The WCTU in Hawaii worked with white business owners and military groups. These groups later took control of the country.

Native Hawaiian women and loyal supporters of the queen formed the Hui Aloha ʻĀina o Na Wahine (Hawaiian Women's Patriotic League). Emilie Widemann Macfarlane started this group on March 27, 1893, to oppose the overthrow and support the queen. Under the leadership of Abigail Kuaihelani Campbell, the group collected 21,000 signatures across the islands in 1897. They were against Hawaii becoming part of the U.S. These efforts stopped a treaty for annexation, but Hawaii was still annexed by a joint resolution of Congress in 1898.

In 1899, the United States Congress began working on making Hawaii a state. Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and others from the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) wrote the "Hawaiian Appeal" in 1899. In this document, they asked Congress to give women the same voting rights as Hawaiian men in the territory. Anthony also wanted to make sure Native Hawaiian men didn't get to vote before women. She and Stanton believed that if new territories joined without women's suffrage, it would make the overall fight for suffrage harder. In the end, voting was limited to men who could read and write English or Hawaiian. Also, the territorial government could not decide on suffrage by itself.

Native Hawaiian women, Nakuina and Wilhelmine Kekelaokalaninui Widemann Dowsett, started organizing for women's suffrage in Hawaii during this time. Emma Nāwahī worked to organize the Democratic Party in Hawaii in 1899. Dowsett founded the National Women's Equal Suffrage Association of Hawai'i (WESAH) in 1912. Carrie Chapman Catt helped the group connect with NAWSA. After WESAH was formed, Catt helped them by representing them at NAWSA's National Suffrage Conventions and staying in touch.

When Catt visited Hawaii to campaign, she talked about "native born" voters being more important than immigrants. This idea appealed to Native Hawaiians who had been colonized by immigrants. However, suffragists in Hawaii also wanted voting rights for immigrants from Asia living in Hawaii. They saw that many second-generation immigrants from Asian countries would soon be able to vote. Dowsett led the effort to include Asian women in the Hawaii suffrage movement. Like many Native Hawaiian women leaders, she saw the value in organizing people from different backgrounds.

The main problem for women's voting rights was the Hawaiian Organic Act. This act created the Territory of Hawaii and specifically stopped the local government from granting suffrage. In 1915, political parties in Hawaii asked their Delegate to Congress, Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole, to bring a bill to the U.S. Congress. This bill would ask for the right for the local government to decide on women's suffrage. The Honolulu Star-Bulletin newspaper believed Congress would act and let Hawaii decide. Prince Kūhiō didn't get attention from Congress that year, but he brought the issue up again in 1916. In 1917, Almira Hollander Pitman, a suffragist from New England, visited Hawaii. She spoke to the local government about women's suffrage and later used her influence to speed up Congress's action.

During World War I, suffragists in Hawaii helped the war effort. They raised money and made clothes. Women got involved in Red Cross work. Women like Emilie Widemann Macfarlane and Emma Ahuena Taylor were important in organizing knitting groups that made items for soldiers. The press and President Woodrow Wilson noticed the work of Hawaiians during the war.

In 1917, Prince Kūhiō brought a bill to the United States Congress, introduced by Senator John F. Shafroth. This bill would allow the territory of Hawaii to make its own decisions about suffrage. In 1918, Pitman helped successfully push for this bill to pass. Pitman used her political connections to help Prince Kūhiō. She, along with Maud Wood Park and Anna Howard Shaw, spoke to the United States House Committee on Woman Suffrage on April 29, 1918. The bill passed and became law in June 1918.

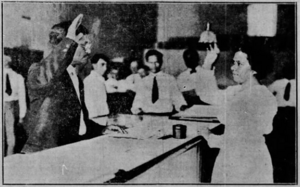

In 1919, suffragists in Hawaii pushed their local government for the right to vote in May 1919. Dowsett organized suffragists to meet at the Hawaii Capitol on March 4, 1919. Several hundred women were in the Senate chamber when an equal suffrage bill passed there.

Dowsett organized another demonstration when the House was going to vote on the bill on March 6. Governor Charles J. McCarthy and Princess Elizabeth Kahanu Kalanianaʻole both spoke in favor of women's suffrage at the rally. Reverend Akaiko Akana also supported women's voting rights. Other people at the rally included Mary Dillingham Frear, Emilie Widemann Macfarlane, and Lahilahi Webb. Margaret Knepper, who had lived in California, shared her experience of voting as a woman.

Instead of passing the Senate bill, the House introduced a different bill. This bill would send the women's suffrage question to voters as a referendum. To protest this, suffragists held demonstrations on March 23. Nearly 500 women of "various nationalities, all ages" went to the House floor. They convinced the representatives to hold a hearing on women's suffrage on March 24. Another demonstration happened that evening at A'ala Park.

Suffragists believed the government's idea to have a referendum instead of directly voting for women's suffrage was just a "trick." They thought it was to hide the fact that some representatives were not serious about giving women the vote. By April 1919, all suffrage bills in the local government had failed. Suffragists then went back to lobbying the U.S. Congress through Prince Kūhiō.

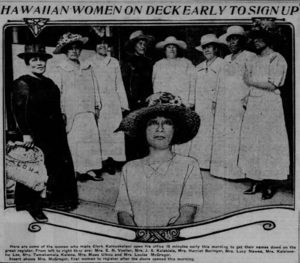

The Nineteenth Amendment was approved in 1920. On August 26, 1920, the Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby ruled that it also applied to women in U.S. territories. The first woman to register to vote in Hawaii was Johanna Papaikaniau Wilcox on August 30, 1920.

Why did some people oppose women's voting rights in Hawaii?

Many arguments against women's suffrage in Hawaii were based on racism. White colonists in Hawaii claimed that Native Hawaiians were not able to govern themselves. One writer against suffrage in 1917 worried about giving the vote to Japanese women. They thought Japanese women would be able to "overtake and outvote the other women" faster than other groups.

People against suffrage from the mainland U.S. also came to Hawaii to promote their cause. Members of the Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women visited Hawaii.