Women in Ancient Greece facts for kids

The lives of women in ancient Greece were very different depending on the city-state they lived in. For example, women in places like Delphi, Gortyn, Thessaly, Megara, and Sparta were allowed to own land. Owning land was a big deal back then, as it was the most important type of private property.

Contents

Women's Rights and Freedom in Ancient Greece

In ancient Greece, women generally did not have the same political or equal rights as men. However, before the Archaic Age, they had more freedom to move around. Records show that women in cities like Delphi, Gortyn, Thessaly, Megara, and Sparta could own land. This was a very important and respected type of property at the time. After the Archaic Age, things changed for the worse. New laws were made that separated men and women more strictly.

Life for Women in Athens

Women in Classical Athens had very few legal rights. They were seen as part of the `oikos` (household), which was led by a male `kyrios` (master). In Athens, a wife was called a `damar`, a word that meant "to control" or "to tame."

Before marriage, a woman was under the care of her father or other male relatives. Once she married, her husband became her `kyrios`. Men usually married around age 30, but girls often married at 14. This was to make sure girls were very young when they got married. It also allowed husbands to choose who their wife would marry next if he died.

Because women could not go to court themselves, their `kyrios` had to do it for them. Athenian women had limited right to property. This meant they were not considered full citizens. In Athens, being a citizen and having rights was linked to owning property.

If a male head of a household died without a son to inherit, his daughter might temporarily get the property. She was called an `epikleros` (heiress). Often, these women would marry a close male relative of their father. Women could get property through gifts, dowries, or inheritance. However, their `kyrios` still had the power to manage or sell their property.

Athenian women could make small deals, like buying something worth less than a "`medimnos` of barley" (a measure of grain). This allowed them to do some small trading. Like women, slaves were not full citizens in ancient Athens. Only gender was a permanent barrier to citizenship. No women ever became citizens in ancient Athens. This meant women were completely left out of Athenian democracy.

Athens was a center for philosophy, and anyone could become a poet, scholar, politician, or artist, except women. Historian Don Nardo said that "most Greek women had few or no civil rights and little freedom." During the Hellenistic period, the famous philosopher Aristotle believed women caused problems and were "useless." He thought women should be kept separate from society. This meant they lived in special parts of homes called a `gynaeceum`. They focused on household duties and had little contact with men. This also helped protect a woman's ability to have children, ensuring they were her husband's. Athenian women received very little education. They learned basic skills at home like spinning, weaving, cooking, and some money management.

Spartan Women's Unique Status

In contrast, Spartan women had more status, power, and respect than women in most other parts of the classical world. Even though Spartan women were not allowed in the military or politics, they were highly respected as mothers of Spartan warriors. Since men were often away fighting, women were in charge of running the family estates.

After many wars in the 4th century BC, Spartan women owned about 60% to 70% of all Spartan land and property. By the Hellenistic Period, some of the richest Spartans were women. They managed their own properties and those of male relatives who were away with the army. Spartan women rarely married before age 20. Unlike Athenian women, who wore heavy, covering clothes and rarely left home, Spartan women wore short dresses and could go where they wanted.

Girls and boys both received an education. Young women, like young men, might have taken part in the `Gymnopaedia` ("Festival of Nude Youths"). Despite having more freedom, Spartan women had the same role in politics as Athenian women: none. Men did not allow them to speak at meetings or take part in any political activities. Aristotle also thought Spartan women's influence was harmful. He argued that their greater legal freedom led to Sparta's downfall.

Women's Rights in Gortyn

In Gortyn, women had a much better position than in other Greek cities. Every woman, even slaves, had some protection under the law. Women in Gortyn, like those in Sparta, could make legal agreements and appear in court. A woman had her own special property that her husband could not control. She could go to court and take oaths about this property.

Husbands and wives had equal rights to divorce. A free divorced woman could even choose to abandon her child. Daughters in Gortyn inherited half of the movable property that their brothers received. An `Epikleros` (called `patrouchoi` in Sparta and Gortyn) had some freedom to choose her husband. If a woman was already married with children and became an `epikleros`, she could choose whether to divorce her husband or not. But a married woman without children who became an `epikleros` had to divorce and marry according to the rules. An heiress could not sell or pledge her inherited property, except to pay off her late father's debts.

Divorce in Ancient Greece

Even with strict limits on women's freedoms, their rights regarding divorce were quite fair for the time. A marriage could end if both people agreed or if one person took action. If a woman wanted a divorce, she needed her father or another male relative to represent her. This was because women were not considered citizens. If a man wanted a divorce, he simply had to send his wife out of his house. A woman's father also had the right to end the marriage.

If a divorce happened, the dowry was returned to the woman's guardian, usually her father. She also had the right to keep half of the goods she had made during the marriage. If the couple had children, the father got full custody. Children were seen as belonging to his household. While divorce laws seemed fair, women rarely divorced their husbands because it could harm their reputation.

Education for Boys and Girls

In ancient Greece, education included cultural training and formal schooling. Young Greek children, but only the boys, were taught reading, writing, and math by a `litterator` (like a modern elementary school teacher). If a family could not afford more education, the boy would start working for the family business or become an apprentice. Girls were expected to stay home and help their mothers manage the household.

If a family had enough money, they could continue to educate their sons. This next level of schooling included learning how to speak well and understand poetry, taught by a `Grammaticus`. Music, mythology, religion, art, astronomy, philosophy, and history were all part of this education.

Daily Life and Home Responsibilities

In ancient Greece, especially Athens, women made up for their lack of legal power by building trust with men. They would create close relationships with their allies. Many women struggled in their personal and public lives. There was a strong focus on the nuclear, male-led `Oikos` (household).

At home, most women had almost no power. They always had to answer to the man of the house. Women often stayed hidden when guests were over. They were usually kept on the upper floors, away from the street door and the public space where the `kyrios` (master) would entertain his friends.

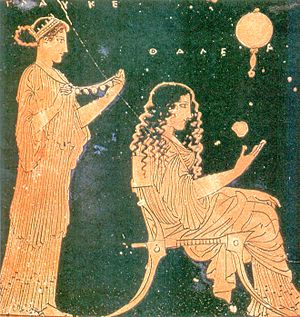

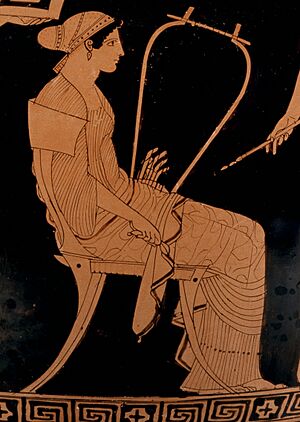

Women were also responsible for maintaining the household. They fetched water from fountain houses, helped organize money, and wove cloth and clothing for their families. From the young age of seven, girls started weaving one of the most famous Athenian textiles, the `peplos` (robe). This was for the holy statue of Athena on the Acropolis. It was a detailed, patterned cloth, usually showing a battle between the gods and giants. It took nine months to finish, and many women helped make it. Athenian women and younger girls spent most of their time making textiles from raw materials, usually wool. Ischomachos told Socrates that his fourteen-year-old wife was very skilled at working with wool, making clothes, and supervising the spinning done by female slaves.

Philosophers' Views on Women

Plato understood that giving women civil and political rights would greatly change families and the state. Aristotle, who was Plato's student, said that women were not slaves or property. He argued that "nature has distinguished between the female and the slave." However, he still thought wives were "bought." He believed women's main job was to protect the household property that men created. According to Aristotle, women's work added no value because "the art of household management is not identical with the art of getting wealth."

In contrast, the Stoic philosophers believed men and women should be equal. They thought sexual inequality went against the laws of nature. They followed the Cynics, who argued that men and women should wear the same clothes and get the same education. Stoics also saw marriage as a moral partnership between equals, not just a biological or social need. They lived by these beliefs. The Stoics adopted the Cynics' ideas and added them to their own theories about human nature, giving their belief in gender equality a strong philosophical base.

|

See also

- Feminism in Greece

- Representation of women in Athenian tragedy

- Women in Classical Athens

- Women in ancient Sparta