Women in Aztec civilization facts for kids

In the ancient Aztec civilization, women had important roles, though some opportunities were limited. As the Aztec empire grew stronger through its military, women's roles became more focused on home life and raising families. They had fewer chances to be equal in other areas. In the 15th century, when the Spanish arrived, they brought their own customs, which changed Aztec culture. However, many old Aztec traditions for women continued and are still remembered today.

Contents

How Did Women's Roles Change in Aztec History?

The lives of Aztec women changed over time. As the Aztec empire focused more on warfare, the idea of everyone being equal became less important.

Marriage in Aztec Society

Aztec marriage customs were similar to those of other groups in Mesoamerica, like the Maya. Aztecs usually married later in life, often in their late teens or early twenties.

How Were Marriages Arranged?

The parents of a young man would usually start the marriage process. After talking with their family, they would contact a professional matchmaker (called ah atanzah). This matchmaker would then speak to the potential bride's family. The young woman's parents would then decide if they accepted the proposal. Young people of both sexes were expected to be celibate, meaning brides were expected to be virgins before marriage.

What Was an Aztec Wedding Like?

An Aztec wedding celebration lasted four days, with the main ceremony on the first day. The bride wore beautiful clothes. Her female relatives would decorate her arms and legs with red feathers and paint her face with a special paste that had small, shiny crystals. The ceremony took place at the groom's parents' house. A fire was lit in the fireplace, and incense was burned as an offering to the gods. The groom's parents gave gifts, like robes and cloaks, to the bride's parents.

To make the marriage official, the matchmaker tied the groom's cape to the bride's skirt. Then, the groom's mother gave the bride and groom each four bites of tamales. Four days of feasting followed the ceremony.

Noble Marriages and Polygamy

Marriages among Aztec nobles were often arranged for political, military, or economic reasons. For example, in 1496, Cosijoeza married Ahuitzotl's daughter to create a strong alliance between the Aztecs and the Zapotecs. Aztec kings reportedly had many wives and children. However, having multiple wives (called polygamy) was only common among Aztec nobles. Most other people in the Aztec civilization had only one spouse (monogamy).

Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Midwives

One of the few powerful roles for women in Aztec society was that of the tlamatlquiticitl, or midwife. These women were very skilled at helping with problems during pregnancy and childbirth. Much of what we know about their practices comes from upper-class Aztec men and Spanish conquerors. Because of this, much of their traditional knowledge has been lost.

The Role of the Tlamatlquiticitl

A tlamatlquiticitl attended every pregnant woman, no matter her social status. Women of higher status often had more than one midwife. The tlamatlquiticitl was essential for helping with birth and giving advice on prenatal care (care before birth).

The Florentine Codex describes much of the advice the tlamatlquiticitl gave to expecting mothers.

- Expecting mothers were told to avoid long periods in a sweat bath. Too much heat was thought to "roast" the child.

- Chewing chicle was not allowed. It was believed the baby would be born with perforated lips and would not be able to suckle.

- Eating earth or chalk was also forbidden, as it was thought to cause poor health in the child.

- The tlamatlquiticitl knew that the baby got its food from the mother. If the mother fasted, the child would starve. So, mothers were told to eat and drink well, even after birth.

- Mothers were warned not to look at anything red. It was believed the child would lie crosswise, making delivery difficult.

- They were not allowed to watch lunar eclipses. It was thought the child would be born with a cleft palate. Eclipses were also linked to miscarriages.

- Mothers were also told not to look at anything that would frighten or anger them, to avoid harming the child.

- Walking around late at night was avoided, as it was believed the child would cry constantly.

- If the mother took naps during the day, the tlamatlquiticitl warned that the child would be born with unusually large eyelids.

- Lifting heavy objects was also thought to damage the baby.

- The tlamatlquiticitl also told others that the expectant mother should not want for anything. All her desires should be met quickly, or the child would suffer.

The tlamatlquiticitl not only gave this advice but also helped with household duties for the expectant mother near the end of her pregnancy. This support, along with advice on managing stress and avoiding heavy lifting, helped the healthy development of their children.

Childbirth Practices

A woman knew it was almost time for delivery when she felt discomfort a few days before. Since the tlamatlquiticitl stayed in the house, the mother was well prepared. If the child was in a breech position (feet first), the tlamatlquiticitl would use massage. She would take the mother into a sweat bath and massage the womb to turn the baby around. The usual position for labor was squatting, as gravity helped push the child out.

To start labor, the tlamatlquiticitl would first give the mother Montanoa tomentosa. If that didn't work, they would give a drink made from possum tail, which was known to cause contractions. In modern studies, many of these mixtures have been shown to induce contractions. However, the Spanish Friars believed these concoctions were witchcraft. Since the tlamatlquiticitl used both ritual and natural elements, the Spanish decided they were evil and stopped these practices.

The act of giving birth was seen as a battle. The tlamatlquiticitl would give the mother a miniature shield and spear for the fight. When the baby was born, the midwife would make battle cries, praising the mother for fighting through labor. The tlamatlquiticitl would cut the umbilical cord, which connects the child to its mother and the gods. It would then be dried. After the placenta came out, it was buried in a corner of the house by the tlamatlquiticitl. The preserved umbilical cords were also buried. Spanish accounts say boys' cords were buried near a battlefield and girls' cords beneath the hearth, to show their future roles. According to birthing almanacs like the Codex Yoalli Ehēcatl, the umbilical cord was planted to ensure the child's connection with the gods.

When Childbirth Was Difficult

If the child died during childbirth, the tlamatlquiticitl would use an obsidian knife to remove the fetus in pieces. This was done to avoid harming the mother. The tlamatlquiticitl warned the mother not to be upset by the loss of her child, or the child's spirit would suffer. The mother's life was always the priority if the situation was life-threatening. Women who died during childbirth were given the same honor as a soldier killed in battle. They were seen as spirits known as cihuateteo.

After delivery, the tlamatlquiticitl stayed in the house to help the mother and check her milk supply. This was important since children would not stop breastfeeding until after 24 months. These four days of monitoring also helped the mother recover quickly. The tlamatlquiticitl would prepare baths and meals for her. After this period, the bathing ceremony took place.

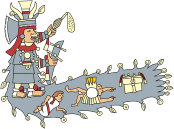

The Bathing Ceremony

The Codex Mendoza shows the bathing ceremony, which the tlamatlquiticitl performed four days after birth. The child was washed in an earthenware tub on a rush mat. On each side of the mat were symbols, one for boys and one for girls.

- For girls, the three objects were related to homemaking: a basket, a broom, and a spindle.

- For boys, there were five objects related to male jobs: an obsidian blade for a featherworker, a brush for a scribe, an awl for carpenters, a tool for goldsmiths, and shields with a bow and arrow for a warrior.

The tlamatlquiticitl circled the mat counter-clockwise with the child. She washed the child, then shouted the name she had chosen for the child as she presented it to the gods. The water used to cleanse the body did not have the same meaning as in a Christian baptism. Instead, it was used to awaken the child's spirit and invite the gods in. The Codex Yoallo Ehēcatl shows this bathing ceremony being performed by the gods. It is understood that the tlamatlquiticitl acted as the gods during these rituals because they looked so similar to what was shown. For example, the Yoallo Ehēcatl shows images of the gods presenting children and cutting the umbilical cord.

After the ceremony, the tlamatlquiticitl would wrap the child in cloths. She would then give a speech to the mother, praising her for her brave fight and telling her it was time to rest. Relatives were then invited to see the child and praise the mother, which marked a successful birth.

Women and Work in Aztec Society

Women mostly worked inside the home. They spun and wove thread from cotton, henepen, or maquey agave plants. They used a handheld drop spindle, then wove cloth using a loom strapped to their backs and held in their laps. Women were also responsible for taking care of turkeys and dogs, which were raised for meat. Any extra cloth, vegetables, or other items were taken by women to the nearest market to be sold or traded for things they needed.

Preparing Food

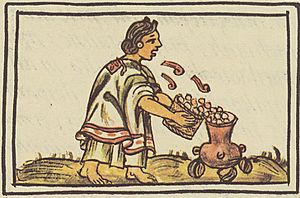

One of the most important jobs for Aztec women at home was preparing maize flour for making tortillas. This is still an important tradition for Mexican families today. Dried maize was soaked in lime water, a process called nixtamalization. The nixtamalized grains were then ground. As part of Aztec manners, men ate before women.

Other Professions for Women

Aztec women also had other jobs. Some were priests, doctors, or sorcerers. Women were often known in their civilization as skilled weavers and crafters.

Images in Aztec codices, ceramics, and sculptures show the detailed and colorful designs made by Aztec weavers. Different regions had their own textile styles and designs. Most designs were geometric, but some regions specialized in textiles with animal and plant images. Cotton was commonly used. Dyes came from blue clays, yellow ochres, and red from insects living in nopal cacti. Purple dye came from the sea snail Purpura patula. This was similar to how the Phoenicians also got purple dye for royal robes from snails.

Unlike men, Aztec women were not forced to join the military. They did not go to military school as young children like all their male counterparts. This meant that while women could not access one of the biggest sources of wealth and respect in Aztec society, they were also killed and sacrificed much less often.

Spanish Rule and Its Impact on Aztec Women

The Spanish conquest of Aztec lands greatly reduced the native population. This happened through warfare and by bringing new diseases, like smallpox, which the Aztecs had no protection against. The people who survived these threats faced big changes to their culture. Spanish customs, such as the Roman Catholic religion, were forced upon them.

Changes to Marriage and Family Life

As early as 1529, the Spanish began forcing Aztecs to convert to Catholicism. They first focused on the Aztec nobility to set an example for others. Nobles like Quetzalmacatzin, King of Amaquemecan (Chalco), were forced to choose only one wife and leave the others. This was to follow the Christian rule of having only one spouse (monogamy). Aztec polygamous arrangements, with secondary wives and children, were not legally recognized by the Spanish. They considered these women and children illegitimate, meaning they could not claim ranks or property. This also broke apart the political and economic structure of Aztec culture, as noble marriages were made with political and land claims in mind.

New Work Demands

Working conditions became very hard for women after the Spanish arrived and the encomiendas (a system of forced labor) were created. Aztec communities had already lost many men to war and diseases. The encomiendas meant that more men worked outside their villages for the encomenderos (Spanish landowners). Traditional gender roles for work became irrelevant. Women no longer had men to do plowing. They were left to do all the farming tasks themselves, including planting and harvesting. They also had to grow enough food to meet the tribute demands of the encomiendas.

Over several generations, many young women left rural areas to work as domestic servants or market vendors in the cities. By the 17th century, Andean women made up most of the market vendors in colonial cities like La Paz (Bolivia), Cuzco (Peru), and Quito (Ecuador).

When the Spanish later set up industrial textile mills, they only hired men to work in them. The new Spanish culture discouraged women from working outside their homes, as their main job was seen as raising children.

See also

In Spanish: Mujeres en la civilización azteca para niños

In Spanish: Mujeres en la civilización azteca para niños

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |