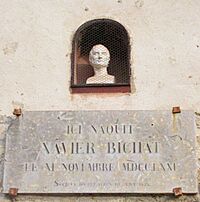

Xavier Bichat facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Xavier Bichat

|

|

|---|---|

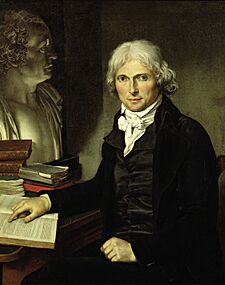

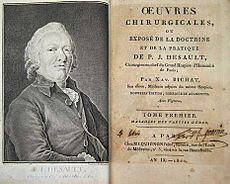

Portrait of Bichat by Pierre-Maximilien Delafontaine, 1799

|

|

| Born |

Marie François Xavier Bichat

14 November 1771 Thoirette, France

|

| Died | 22 July 1802 (aged 30) Paris, France

|

| Resting place | Père Lachaise Cemetery |

| Known for | the concept of tissue |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Histology Pathological anatomy |

| Signature | |

|

|

Marie François Xavier Bichat (born November 14, 1771 – died July 22, 1802) was a French doctor who studied the human body. He is known as the father of modern histology, which is the study of the body's tissues.

Even without a microscope, Bichat identified 21 different types of basic tissues. These tissues make up all the organs in the human body. He was the first to suggest that tissues are a key part of human anatomy. He saw organs as collections of different tissues, not just single parts.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Xavier Bichat was born in Thoirette, France. His father, Jean-Baptiste Bichat, was a doctor and taught him a lot. Xavier was the oldest of four children.

He went to college in Nantua and later studied in Lyon. He was very good at mathematics and physical sciences. But he decided to focus on studying anatomy (the body's structure) and surgery. He learned from Marc-Antoine Petit, a top surgeon in Lyon.

In 1793, Bichat worked as a surgeon with the French army. In 1794, he moved to Paris. There, he became a student of Pierre-Joseph Desault, a famous surgeon at the Hôtel-Dieu hospital. Desault was so impressed with Bichat that he treated him like his own son. Bichat helped Desault with his work and also did his own research.

Desault died suddenly in 1795. This was a very sad time for Bichat. He helped Desault's family and finished the last part of Desault's medical journal. In 1796, Bichat and other doctors started the Société Médicale d'Émulation. This group was a place for doctors to discuss new ideas in medicine.

Teaching and Discoveries

In 1797, Bichat started teaching anatomy. He was very successful, so he expanded his lessons to include surgery. He also worked on organizing Desault's surgical ideas into a book called Œuvres chirurgicales de Desault (1798–1799). In this book, Bichat showed how well he understood surgery, even though he was presenting someone else's ideas.

In 1798, he also taught a separate course on how the body works (physiology). He became ill for a while, but as soon as he recovered, he went back to work with great energy.

Bichat's next important book was Traité des membranes (Treatise on Membranes), published in 1800. In this book, he explained his idea of tissue pathology and described 21 different tissues. This book quickly became a very important text in medicine.

He then published Recherches physiologiques sur la vie et la mort (Physiological Researches upon Life and Death, 1800). After that came his four-volume work, Anatomie générale (1801). This book contained his most important and original research. He also started another book, Anatomie descriptive (1801–1803), but only finished two volumes before he died.

Last Years and Passing

In 1800, Bichat became a doctor at the Hôtel-Dieu hospital. He started examining many bodies to understand how diseases changed different organs. In less than six months, he examined over 600 bodies. He also wanted to know more precisely how medicines worked. So, he did experiments that gave him a lot of valuable information. Towards the end of his life, he was also working on a new way to classify diseases.

On July 8, 1802, Bichat fainted while going down stairs at the Hôtel-Dieu. He had spent a lot of time examining skin that was decaying, which might have caused him to catch typhoid fever. The next day, he had a bad headache. He got worse and died on July 22, at only 30 years old.

Jean-Nicolas Corvisart, another doctor, wrote to the French leader Napoleon Bonaparte: "Bichat has fallen on a battlefield that has many victims; no one has done so much and so well in such a short time."

Ten days later, the French government put his name, along with Desault's, on a special plaque at the Hôtel-Dieu.

Bichat was first buried in Sainte-Catherine Cemetery. Later, his remains were moved to Père Lachaise Cemetery in 1845. A large group of people attended his reburial after a service at Notre-Dame.

Ideas on Life

Bichat believed in Vitalism. This idea suggests that living things have a special "vital force" that cannot be explained by just physics or chemistry.

In his book Physiological Researches upon Life and Death (1800), Bichat defined life as "all the functions that fight against death." He also said that "everything around living bodies tends to destroy them."

Bichat thought that animals had special living properties. He divided life into two parts:

- Organic life: This was the life of inner organs like the heart and intestines. He believed it was controlled by a system of small "brains" in the chest.

- Animal life: This involved organs like the eyes, ears, and limbs. It included habits, memory, and was controlled by the main brain. This part of life could not exist without the heart.

Lasting Impact

Bichat's most important contribution was his idea that organs are made of specific tissues or "membranes." He described 21 such membranes, including connective tissue, muscle tissue, and nerve tissue. He explained in Anatomie générale: "Chemistry has its simple elements, which combine to form complex things... In the same way, anatomy has its simple tissues, which combine to make up the organs."

Bichat did not use a microscope because he did not trust them. Because of this, his studies did not include the idea of cells. However, he was an important link between the study of diseases in organs (by Giovanni Battista Morgagni) and the later study of diseases in cells (by Rudolf Virchow). Bichat realized that diseases were specific conditions that started in particular tissues.

The philosopher Michel Foucault saw Bichat as a key figure in understanding the human body as the source of illness. Bichat's ideas changed how people thought about the body and disease.

Honors and Recognition

- A large bronze statue of Bichat was put up in Paris in 1857.

- Bichat is also shown on the front of the Panthéon building in Paris.

- His name is one of the 72 names written on the Eiffel Tower.

- A hospital in Paris, the Bichat–Claude Bernard Hospital, is named after him.

The writer George Eliot wrote about Bichat's life in her 1872 novel Middlemarch. In Madame Bovary (1856), Gustave Flaubert wrote about a doctor character who belonged to the "great school of surgery that sprang up around Bichat."

Images for kids

-

Relief of Bichat on the pediment of the Panthéon.

-

Statue by D'Angers in Bourg-en-Bresse.

-

Bust at the University of Zaragoza College of Medicine.

See also

In Spanish: Xavier Bichat para niños

In Spanish: Xavier Bichat para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |