Émile Cohl facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Émile Cohl

|

|

|---|---|

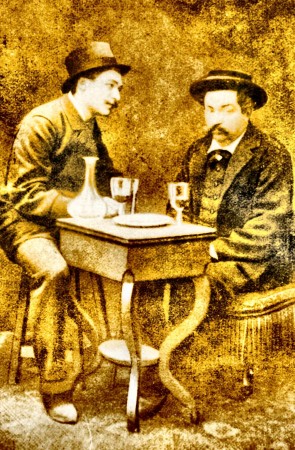

Young Émile Cohl

|

|

| Born | 4 January 1857 Paris, France

|

| Died | 20 January 1938 (aged 81) Villejuif, France

|

|

Notable work

|

Le Peintre néo-impressionniste |

| Movement | Incoherent Movement |

| Spouse(s) | Unknown spouse; Suzanne Delpy (June 1896) |

| Patron(s) | André Gill |

Émile Eugène Jean Louis Cohl (born Courtet; 4 January 1857 – 20 January 1938) was a French artist. He drew funny pictures (caricatures), cartoons, and animated films. He was part of a group called the Incoherent Movement. Many people call him "The Father of the Animated Cartoon."

Contents

Émile Cohl's Life Story

Émile's father, Elie, sold rubber. His mother, Emilie Laure, was a seamstress who sewed linen. Elie's rubber factory often had problems. This meant the family had to move homes a lot in Paris.

Early Years and Discoveries

Émile's father was often busy. Émile lived with his sick mother until she passed away in 1863. In 1864, when he was 7, he went to a boarding school called Institute Vaudron. There, people noticed and encouraged his artistic talents. The next year, he had a cold and stayed in his father's apartment. He started stamp collecting, which later became his only way to earn money several times in his life.

The Franco-Prussian War and the siege of Paris caused big problems. Elie Courtet's rubber factory closed. Émile moved to a different school, Ecole Turgot. But he soon stopped focusing on lessons. Instead, he wandered the streets of Paris to see history happening. He found two things that became very important to him: Guignol puppet theater and political caricatures.

Guignol was a type of play, often about love. Puppets played the characters. A special type of Guignol was Fantoche. In Fantoche, the puppeteer put their head through a hole in a black sheet, with a small puppet body below.

Political caricatures started in France during the Second French Empire. But Emperor Napoleon III had stopped them. During the short time of the Commune (about 11 weeks), artists were free to put up posters on the streets. The main place for this was Rue du Croissant, close to Ecole Turgot.

In 1872, Elie Courtet sent his 15-year-old son to train with a jeweler for three years. Émile drew funny pictures. He also joined the army in Cherbourg and drew more. Elie then placed him with a person who helped people get insurance for ships. Émile left that job and took a much lower-paying job as a philatelist (stamp collector). He said he preferred drawing, living an artistic life, and even going hungry if needed.

Working with André Gill

In 1878, Émile got a recommendation letter from Étienne Carjat. He used it to ask André Gill for a job. Gill was the most famous caricaturist of that time. Gill became famous ten years earlier by publishing La Lune, a magazine that criticized Napoleon III. His printing machines were destroyed, and he was put in jail. In 1876, he started La Lune Rousse to continue his work. By then, he was making fun of how silly ordinary, middle-class life could be. But the government was becoming more open, so he had fewer big targets. La Lune Rousse closed in 1879.

Émile Courtet's job was to help Gill by finishing backgrounds for his drawings. He might have drawn some illustrations himself. While doing this, he developed his own caricature style, based on Gill's. Gill's style showed a large, recognizable head of the person (with a kind expression) on a small puppet body (doing something silly). This clearly came from Fantoche puppetry. Émile used this style and added details to show movement and ideas from other Guignol puppet shows. Around this time, he started using the name Émile Cohl. The meaning of "Cohl" is unclear. It might come from the dark makeup called "kohl," or it might mean Émile stuck to his teacher Gill like glue (colle in French). Maybe he chose it because it sounded unusual. A drawing of a glue pot appears in some of Cohl's caricatures.

Adolphe Thiers was followed as president by Patrice MacMahon, duc de Magenta. MacMahon was a conservative who wanted a king. He became less and less popular because of the funny drawings made about him. One of these, "Aveugle par Ac-Sedan," was a French joke. It sent its creator, Émile Cohl, to jail on October 11, 1879. This made him famous right away. Three months later, MacMahon quit because he was embarrassed. The artists who drew caricatures liked to think they were responsible. Jules Grévy became president next. He moved the real power from the president to the prime minister and lawmakers. This led to a time of peace and good times for France.

Through Gill, Cohl (as he was now known) met an art group called the Hydropathes. This group shared new ideas and loved poetry. Like many groups at the time, they tried to surprise people. Because he was now famous, Cohl became the editor of the group's magazine, L'Hydropathe, in October 1879. Around this time, his father, who he hadn't been close to, passed away and left him a small inheritance. Cohl tried to find out what he was good at. He wrote and produced two funny plays, but they weren't very popular. The co-author of both plays was Norés (whose real name was Edouard Norés). Norés was an American who had been an architect before choosing an artistic life by the Seine River. Besides being good friends, Norés taught Cohl English, which was helpful later.

The Incoherents and Gill's Death

Cohl got married on November 12, 1881. His wife later left him for a writer. At the same time, André Gill was sent to the Charenton mental hospital. He got better in a few months. In 1882, he sent his first serious painting, Le Fou (The Madman), to the Salon. The painting wasn't liked by the artists at the Salon, which sent him back to Charenton.

Meanwhile, the Hydropathes group broke up in 1882. The Incoherents group took their place in Cohl's life. Jules Lévy started the Incoherents. He came up with the name "les arts incohérents" (incoherent arts) to be different from "les arts décoratifs" (decorative arts). The Incoherents were even less interested in politics than the Hydropathes. Their motto was "Happiness is truly French, so let's be French." They focused on silly ideas, dreams, and drawings like children make. Cohl's Incoherent art joined his caricatures and funny news reports at La Nouvelle Lune. He had become the main writer and temporary editor there. He became editor-in-chief in November 1883.

By that time, the Incoherents were so popular that a show was set up at the Vivienne Gallery for everyone to see. It was called "an exhibition of drawings by people who do not know how to draw." Cohl's drawing was called Portrait garanti ressemblant (Portrait—Resemblance Guaranteed). The show accepted any and all entries, as long as they were not rude or serious. The public really liked the show, and the money earned was given to help people. There was a second show in 1884. The 1885 show was replaced by a costume party (Cohl went dressed as an artichoke). In 1886, Cohl made his most unusual and typical work in the Incoherent style: Abus des metaphors (Abuse of Metaphors). This was a collection of more than a dozen colorful sayings brought to life in drawings.

Cohl's personal life was not as good as his work life seemed. This was true even though his daughter Marcelle Andrée was born in May 1883. Gill never got his sanity back. After a few months, Charenton hospital took his belongings and drawings. They sold them to pay for his care. Cohl could not keep his hero in the public eye. Gill died on May Day, 1885, with only Cohl by his side. Cohl never forgot how his friends and the public forgot about Gill. The Incoherent movement ended in 1888.

After his marriage ended, Cohl moved to London. He worked for Pick Me Up, a funny magazine that liked French artists. He left his other job as a stamp collector at this time. He came back to Paris in June 1896 and married Suzanne Delpy. She was the daughter of one of Gill's followers. Their son André Jean was born on November 8, 1899. By this time, Cohl had stopped drawing funny pictures of people. He sent funny drawings to magazines about bikes, families, and kids. He also wrote articles about French history, stamps, and fishing. In July 1898, he started writing for L'Illustré National. This is where Cohl's comic strips began. At the same time, Cohl's art changed from just showing scenes to telling stories. His style also changed from Gill's puppet-like style to Impressionism (a painting style). Other things he was interested in during this time included puzzles, toys (he even invented some new ones), and drawings of figures made from wax matches. In politics, he sent drawings against Dreyfus (a famous political case) to La Libre Parole Illustrée.

Motion Pictures and Animation

By 1907, Émile Cohl was 50 years old. Like everyone else in Paris, he knew about motion pictures. How he actually started in the movie business is not entirely clear. According to Jean-Georges Auriol in a 1930 book, Cohl was walking down the street one day. He saw a poster for a movie that looked like it copied one of his comic strips. Very angry, he went to the manager of the studio (Gaumont) and was hired right away to write movie ideas. This story is probably not completely true about which comic and film. It's also possible the story is false. Cohl might have been asked to join by director Etienne Arnaud or art director Louis Feuillade. Both had worked for caricature papers before, so they might have known Cohl by his reputation.

At Gaumont, Cohl worked with other directors when he could. He learned how to film from Arnaud. He directed exciting chases, funny movies, féeries ("fairy pieces"), and big shows. But his special skill was animation. He worked in a corner of the studio with a Gaumont camera set up vertically and one helper to use it. He made four animated parts each month to add into movies that were mostly live-action. The studio director, Léon Gaumont, called him "the Benedictine" (a type of monk known for hard work) during one of his visits.

The idea for animation came from the very popular film The Haunted Hotel. This film was released by Vitagraph and directed by J. Stuart Blackton. It was first shown in Paris in April 1907. People immediately wanted more movies that used its amazing way of making objects move. According to a story told by Arnaud in 1922, Gaumont had told his staff to figure out the "mystery of 'The Haunted Hotel'." Cohl watched the film frame by frame and learned how animation worked. Cohl, who always wanted to be more famous later in life, never said this story was true. Also, many films were released before 1907 with stop-motion or drawn animation. Blackton and others made them. Any of these could have taught Cohl animation, or he might have figured it out himself. The Haunted Hotel was important because it was popular enough to make the hard work of animation worth the money.

Cohl made Fantasmagorie from February to June 1908. This is thought to be the first fully animated film. It had 700 drawings. Each drawing was shown twice, making the film almost two minutes long. Even though it was short, the film was full of ideas that flowed like a "stream of consciousness". It used ideas from Blackton, like a "chalk-line effect." This was done by filming black lines on white paper, then reversing the film to make it look like white chalk on a black board. It also had the main character drawn by the artist's hand on camera. The main characters were a clown and a gentleman (taken from Blackton's Humorous Phases of Funny Faces). The film, with all its wild changes, was a direct tribute to the Incoherent movement, which was forgotten by then. The title refers to the "fantasmograph," an old magic lantern that showed ghostly images floating on walls.

Fantasmagorie was released on August 17, 1908. After this, he made two more films: Le Cauchemar du fantoche ("The Puppet's Nightmare") and Un Drame chez les fantoches ("A Puppet Drama"). Both were finished in 1908. These three films all used the chalk-line style, stick-figure clown main characters, and constant changes. Cohl made up the plots of these films as he was filming them. He would put a drawing on a light box, photograph it, then trace it onto the next sheet with small changes, photograph that, and so on. This meant the pictures didn't jump around, and the story was spontaneous. Cohl had to plan the timing beforehand. This process was hard and took a lot of time. This is probably why he stopped doing drawn animation after Un Drame chez les fantoches.

The other films Cohl made for Gaumont included strange changes (Les Joyeux Microbes [The Joyous Microbes] (1909)). Some had great special effects with mattes (Clair de lune espagnol [Spanish Moonlight] (1909)). He also made loving puppet animation (Le Tout Petit Faust [The Little Faust] (1910)). Other films used jointed cut-outs or animated matches (the matches were a special favorite of Cohl's).

During his lifetime, Cohl's most famous film was Le Peintre néo-impressionniste ["The Neo-Impressionistic Painter"], made in 1910. In this film, an artist is sketching a model holding a broom. The model is drawn as a stick-figure. A collector then rushes in, asking about the progress of his work. The artist shows the collector a series of blank colored canvases (the film has color tints). As he gives their silly titles, the collector imagines them being drawn on the canvas. For example, the red canvas is A cardinal eating lobster with tomatoes by the banks of the Red Sea. The collector soon gets so excited that he buys every blank canvas he sees. Clearly, the artist is not a neo-Impressionist (a new art style in Paris). He is an Incoherent artist.

Cohl's animated films had a big impact because they were shown in America by Kleine. Many of them received great reviews in movie magazines. But Cohl was only called "Gaumont's animator." It was probably because of Fantasmagorie that Winsor McCay made Little Nemo (1911). Some of Cohl's ideas can be seen in Little Nemo and later films by McCay. For example, the dots forming Little Nemo are like effects in Un Drame Chez les Fantoches and Les Joyeux Microbes. The rose changing into the Princess might have been inspired by Fantasmagorie. The main character in The Story of a Mosquito (1912) sharpening his beak comes from Un Drame Chez les Fantoches. McCay throwing a pumpkin to Gertie the Dinosaur (1914) (mixing live-action and animation) might have been an answer to the matador throwing his hatchet at the moon in Clair de lune espagnol. But even if McCay borrowed from Cohl, McCay's films also had a lot of unique style and spirit.

On November 30, 1910, Cohl left Gaumont for Pathé, probably for more money. He made only two animated films before he had to direct only live-action movies. These were comedies starring Jobard (Lucien Cazalis), one of the first great movie comedians. Cohl made ten Jobard films between March and May 1911 before taking a vacation. One of these films might have been the start of pixilation. This is a technique where stop-motion is used with human beings.

One of those two animated films was Le Ratapeur de cervelles ["Brains Repaired"]. This was a remake of Les Joyeux Microbes but about a mental illness. The changes in this film are some of the most amazing and nonsensical of Cohl's career. For example, two men shake hands, and their heads grow into huge crossed bird beaks. These fill the screen until only their shared eye is seen, which then grows into a bellows. The other film, La Revanche des esprits [The Spirit's Revenge] (now lost), might have been the first film to mix live-action and animation by drawing directly on the live-action film. (Before this, only mattes were used).

In September 1911, Émile Cohl learned that his daughter Andrée had died. He was not happy with Pathé and too proud to go back to Gaumont. So, Cohl signed with Eclipse in September. Only two of Cohl's Eclipse films have survived. One of them, Les Exploits de Feu Follet (also known as The Nipper's Transformations), is now seen as the first Western animated film definitely shown in a Japanese cinema (on April 15, 1912). The Eclipse contract was not exclusive, so Cohl made films for other studios. One of these films, Campbell Soups, was his first film made for Éclair, the third-largest studio in France.

In the early 1900s, many early film studios in America were in Fort Lee, New Jersey. Éclair's American studio was run by Cohl's friend Arnaud. As Éclair was making comedies for American audiences, it was easy for Arnaud to have his friend sent across the Atlantic to join him. Cohl, his wife Suzanne, and their son André sailed first class from Le Havre to New York City. At Ellis Island, he had to shave off the mustache he had worn for thirty years, in honor of André Gill. This was for "sanitary reasons."

Even with some unfriendly feelings from locals, the French group in Fort Lee was excited to finally be in the American market. Cohl bought a house and lived a typical middle-class American life. He had a big advantage over other Éclair employees because he spoke English fluently.

Cohl had two main jobs at Fort Lee: funny newsreel inserts and The Newlyweds animated series. The newsreel (one of the first of its kind) was started by the Sales Company in March 1912 and continued by Universal (Éclair's distributor). The Newlyweds started as a newspaper comic strip by George McManus in the New York ''World''. The three main characters were a fashionable woman, her helpful husband, and Baby Snookums. Baby Snookums was a wild child who always got what he wanted, usually at the father's expense. The series was popular in both the United States and France (where it was called Le Petit Ange). Cohl wanted to make the first animated series, and he liked The Newlyweds. McManus might have been convinced to sign with Cohl because of his friend Winsor McCay. Before this, some comic series had been made into films, but they were all live-action. Examples include Happy Hooligan, Buster Brown, and Mutt and Jeff (which later became a successful animated series).

Cohl started working on The Newlyweds series in November 1912. The films began appearing in theaters in March 1913. The ads for the Newlyweds films are the oldest known to use the phrase "animated cartoons." As was common for all comic adaptations that followed, only the comic artist was mentioned in the advertising, never the animator. Cohl worked fast (13 Newlyweds cartoons in 13 months). He used very little actual animation. The scenes were mostly still pictures with speech bubbles appearing above each character's head (done in McManus's style). The small amount of movement needed was done with hinged cut-out figures animated by stop-motion. The only clever part of these films was the way scenes changed, which used Cohl's special transformations. Still, Cohl had shown that making animated films for money was possible. The series was an instant hit. Only one film from this series has survived, "He Poses for His Portrait" (1913).

The success of the series led to a boom in animation. All were adaptations of newspaper comic strips, and few are remembered today. Meanwhile, Cohl saw both The Story of a Mosquito and Gertie the Dinosaur live at the Hammerstein Theater in New York. He wrote in his diary how much he admired each. For animation to be practical, it had to move beyond Cohl's (cut-outs) and McCay's (tracing) techniques. Both were hard, one-person processes. Two men independently found ways around this problem: Raoul Barré and John Randolph Bray. Barré studied art in Paris in the 1890s and was known for his cartoons supporting Dreyfus. In 1920, Cohl told a story about two unnamed visitors that Éclair had forced on him to study his techniques. He said they later stole these techniques to make their own series. It's possible these two were Barré and his business partner William C. Nolan. Cohl's clear dislike for his visitors might have been because they were on opposite sides in the Dreyfus Affair. On the other hand, Barré's method for making cartoons quickly, the "slash system," is the exact opposite of Cohl's cut-out system. It is true that Barré's series, The Animated Grouch Chasers, often copied characters and stories from Cohl, but everyone was doing that. Animation historian Michael Barrier thinks one of Cohl's unnamed visitors might have been Bray instead of Barré.

World War I and Later Years

On March 11, 1914, the Cohl family left New Jersey for Paris because of a death in Suzanne's family. They never returned. Eight days later, a fire destroyed most of Éclair's American films. This included all but two of Cohl's films: He Poses for His Portrait and Bewitched Matches. The latter is the only one of Cohl's animated matches films to survive. The American studio later moved to Tucson, Arizona. The problems from the fire almost stopped Éclair's work in France. Cohl made a few films for Éclair in France. But World War I started on August 3, 1914. This meant those films were held back for years before being released.

By August 11, 80% of the French film industry had joined the army or been drafted. Cohl, at 57 years old, was too old to fight. But he volunteered as much as he could while working at Éclair. His heart was no longer in his work, because his beloved wife Suzanne was slowly dying. In 1916, American cartoons became very popular in France. Gaumont imported The Animated Grouch Chasers. For the first time since Blackton's early films, animated films were advertised with the animator's name and face, Raoul Barré. If Barré was the person who "stole" Cohl's techniques, this must have made Cohl very angry. It didn't help that his former employer was making all the fuss.

At this time, Benjamin Rabier, a popular children's book illustrator, approached Cohl. Rabier wanted Cohl to animate his characters. The producer for the series was René Navarre, a former actor famous for playing the anti-hero Fantomas in films from 1913 and 1914. The distributor was Agence Générale Cinematographique (AGC). The three parted ways because Cohl was upset he wasn't being given credit in the advertising. The series, Les Dessins animés de Benjamin Rabier (The Animated Drawings of Benjamin Rabier), starred Flambeau the War Dog. The only surviving film, Les Fiançailles de Flambeau [Flambeau's Wedding] (released 1917), has cute, natural characters from Rabier and dark, funny humor from Cohl. By the time Cohl left, Rabier had learned enough animation to continue with two helpers. The series lasted for several years.

Cohl continued working with Éclair during this time, mostly making newsreel inserts. Based on the few parts that remain, the series Les Aventures des Pieds Nickelés [Adventures of the Leadfoot Gang] might have been Cohl's best work. It was based on a working-class comic strip by Louis Forton about a group of young anarchists who constantly got into trouble with criminals and the law. The series ended because of the war. The Éclair-Journal studios were used to make American war propaganda.

Cohl spent the rest of the war serving his country. He joined the United States Air Service Supply as a volunteer on May 11, 1918. His son André had joined the American Transportation Division the previous November.

After the war, Cohl quit Éclair in May 1920. He made his last important film, Fantoche cherche un logement ["Puppet Looks for an Apartment"]. It was released as La Maison du fantoche ["Puppet's Mansion"] in April 1921 by AGC. The movie magazines only gave it a one-line plot summary. No one cared about Cohl's work anymore, or any other French filmmaker. Cohl's career was over. There was no longer a way to justify the cost of an animated short film in a world of live-action feature films.

Cohl's money problems got worse during the Great Depression. He lived in severe poverty for years. While his friend George Méliès received the Legion of Honor medal in 1931, Cohl's pioneering work in animated film received little attention. In the spring of 1937, at age 80, his face was slightly burned when a candle on his desk set his beard on fire. During a couple of months in a charity hospital, young film journalist René Jeanne helped organize a special showing of Cohl's work. It played at the Champs-Elysées Cinema on January 19, 1938, the day before Cohl died, two weeks after his 81st birthday. Coincidentally, Georges Méliès died hours later.

Cohl's ashes are kept in the columbarium of the Père-Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

Filmography as a Director

- N.I.-Ni- C'est fini (1908)

- L' hôtel du silence (1908)

- Le violoniste (1908)

- le veau (1908)

- Le prince Azur (1908)

- Le petit soldat qui devient Dieu (1908)

- Le mouton enragé (1908) (co-director)

- Le miracle des roses (1908)

- Le journal animé (1908)

- Le coffre-fort (1908)

- La vengeance de Riri (1908)

- L' automate (1908)

- La monnaie de mille francs (1908)

- La force de l' enfant (1908)

- La course aux potirons (1908) (co-director)

- Et si nous buvions un coup (1908)

- Blanche comme neige (1908)

- Fantasmagorie (1908)

- Le cauchemar de Fantoche (1908)

- Le cerceau magique (1908)

- Un drame chez les fantoches (1908)

- Les allumettes animées (1908)

- Les frères Boutdebois (1908)

- La séquestrée (1908)

- Un chirurgien distrait (1909)

- Monsieur Clown chez le Lilliputiens (1909)

- Moderne école (1909) (co-director)

- Les Transfigurations (1909)

- Le Spirite (1909)

- Les Locataires D'à-Côté (1909)

- Les Grincheux (1909)

- Les Chaussures Matrimoniales (1909)

- Les Chapeaux Des Belles Dames (1909)

- Le Docteur Carnaval (1909)

- L' Armée d' Agenor (1909)

- La Bataille d'Austerlitz (1909)

- Affaires de Coeur (1909)

- Soyons Donc Sportifs (1909) (co-director)

- La Valise Diplomatique (1909) (co-director)

- La Lampe Qui File (1909)

- L' Agent Du Poche (1909)

- Japon de Fantaisie (1909)

- Clair de lune espagnol (1909) (co-director)

- L' Omelette Fantastique (1909) (co-director)

- Les Beaux-Arts De Jocko (1909)

- La vie à rebours (1909)

- Pauvre Gosse (1909)

- L' éventail animé (1909) (co-director)

- Les Jojeux Microbes (1909)

- Les Couronnes I (1909)

- les Couronnes II (1909)

- Porcelaines Tendres (1909)

- Génération Spontanée (1909)

- Don Quichotte (1909)

- Le Miroir Magique (1909)

- La Ratelier De La Belle-Mère (1909)

- La Lune Dans Son Tablier (1909)

- Les Lunettes Féeriques (1909)

- Toto Devient Anarchiste (1910)

- Rien n'est impossible à l' homme (1910)

- Rêves Enfantins (1910)

- Monsieur Stop (1910)

- Mobilier Fidèle (1910)

- Les chefs-d'oeuvre de Bébé (1910)

- Les Chaînes (1910)

- Le Placier est Tenace (1910)

- Le Petit Chantecler (1910)

- Le Peintre Néo-Impressioniste (1910)

- L' Enfance De l' Art (1910)

- Le Grand Machin et le Petit Chose (1910)

- La Télécouture Sans Fil (1910)

- La Musicomanie (1910)

- Histoire de Chapeaux (1910)

- En Route (1910)

- Dix Siècles D' élégance (1910)

- Bonsoirs Russes (1910)

- Bonsoirs (1910)

- Le Binettoscope (1910)

- Champion De Puzzle (1910)

- Le Songe D' Un Garçon De Café (1910)

- Cadres Fleuris (1910)

- Le Coup De Jarnac (1910)

- Le Tout Petit Faust (1910)

- Les Douze Travaux d'Hercule (1910)

- Singeries Humaines (1910)

- Les Quatres Petits Tailleurs (1910)

- Les Fantaisies D' Agénor Maltracé (1911)

- Les Bestioles Artistes (1911]

- Le Repateur De Cervelles (1911)

- Le Musée Des Grotesques (1911)

- Le Cheveu Délateur (1911)

- La Vengeance Des Espirits (1911)

- La Chambre Ensorcelée (1911)

- La Boîte Diabolique (1911)

- Jobard, Portefaix Par Amour (1911)

- Jobard ne veut pas voir les femmes travailler (1911)

- Jobard ne veut pas rire (1911)

- Jobard, garçon de recettes (1911)

- Jobard, fiancé par interim (1911)

- Jobard est demandé en mariage (1911)

- Jobard chauffeur (1911)

- Jobard change de bonne (1911)

- Jobard à tue sa grand-mère (1911)

- Jobard, amoureux timide (1911)

- C'est roulant (1911)

- Aventures d'un bout de papier (1911)

- Les Exploits de Feu Follet (1911)

- Une Poule Mouilléé Qui Se Sèche (1912)

- Ramoneur Malgré Lui (1912)

- Quelle Drôle De Blanchisserie (1912)

- Poulot N'est Pas Sage (1912)

- Moulay Hafid et Alphonse XIII (1912)

- Les Métamorphoses Comiques (1912)

- Les Jouets Animes (1912)

- Les Extraordinaires Exercices De La Famille Coeur-de-Buis (1912)

- Les Exploits De Feu-Follet (1912)

- Le Prince de Galles et Fallières (1912)

- Le premier jour de vacances de Poilot (1912)

- Le marié à mal aux dents (1912)

- La Marseillaise (1912)

- La Baignoire (1912)

- Jeunes Gens à marier (1912)

- Fruits Et Légumes Vivants (1912)

- Dans La Valléé D'Ossau (1912)

- Monsieur de Crac (1912)

- Campbell Soups (1912)

- War in Turkey (1913)

- Rockefeller (1913)

- Il Joue Avec Dodo (1913)

- I Confidence (1913)

- Castro in New York (1913)

- Carte Américaine (1913)

- The Subway (1913)

- Milk (1913)

- Graft (1913)

- Coal (1913)

- When He Wants a Dog, He Wants A Dog (1913)

- Business Must Not Interfere (1913)

- Wilson and the Hats (1913)

- Wilson and the Broom (1913)

- Universal Trade Marks (1913)

- The Two Presidents (1913)

- The Police Women (1913)

- The Auto (1913)

- Poker (1913)

- Gaynor and the Night Clubs (1913)

- He Wants What He Wants When He Want It (1913)

- Poor Little Clap He Was Only Dreaming (1913)

- Wilson and the Tariffs (1913)

- The Masquerade (1913)

- The Brand Of California (1913)

- Bewitched Matches (1913)

- He Loves To Watch The Flight of Time (1913)

- The Two Suffragettes (1913)

- The Safety Pin (1913)

- The Red Balloons (1913)

- The Mosquito (1913)

- He Ruins His Family's Reputation (1913)

- He Slept Well (1913)

- He Was Not Ill, Only Unhappy (1913)

- Uncle Sam and his Suit (1913)

- The Polo Boat (1913)

- The Cubists (1913)

- The Artist (1913)

- It Is Hard to Please Him But It Is Worth It (1913)

- He Poses For His Portrait (1913)

- Wilson's Row Boat (1913)

- Clara and her Mysterious Toys (1913)

- The Hat (1913)

- Thaw and the Lasso (1913)

- Bryant and the Speeches (1913)

- A Vegetarian's Dream (1913)

- Thaw and the Spider (1913)

- He Loves to be Amused (1913)

- Unforeseen Metamorphosis (1913)

- He Likes Things Upside Down (1913)

- Pickup Is A Sportsman (1913)

- Zozor (1914)

- What They Eat (1914)

- The Terrible Scrap Of Paper (1914)

- The Greedy Neighbor (1914)

- The Bath (1914)

- The Anti-Neurasthenic Trumpet (1914)

- Ses Ancêtres (1914)

- Serbia's Card (1914)

- Le ouistiti de Toto (1914)

- L' enlèvement de Denajire Goldebois (1914)

- L' avenir dévoilé par les lignes de pieds (1914)

- He Does Not Care To Be Photographed (1914)

- Il aime le bruit (1914)

- Society at Simpson Center (1914)

- Les allumettes fantaisistes (1914)

- The Social Group (1914)

- Une drame sur la planche à chaussures (1915)

- Fantaisies truquées (1915)

- Éclair Journal (1915)

- Pulcherie et ses meubles (1916)

- Pages d' histoire number 1 and 2 (1916)

- Mariage par suggestion (1916)

- Les victuailles de Gretchen se révoltent (1916)

- Les tableaux futuristes et incohérents (1916)

- Les fiançailles de Flambeau (1916)

- Les exploits de Farfadet (1916)

- Les évasions de Bob Walter (1916)

- Les braves petits soldats de plomb (1916)

- Les aventures de Clémentine (1916) (co-regisseur)

- La main mystérieuse (1916)

- La journée de Flambeau (1916) (co-regisseur)

- La campagne de France 1814 (1916)

- La blanchisserie américaine (1916)

- Jeux de cartes (1916)

- Flambeau au pays des surprises (1916)

- Figures de cire et têtes de bois (1916)

- Éclair Journal: Série (1916)

- Croquemitaine et Rosalie (1916)

- Comment nous entendons (1916)

- Les aventures des Pieds-Nickelés (1918)

- La maison du Fantoche (1921)

See also

In Spanish: Émile Cohl para niños

In Spanish: Émile Cohl para niños

- Paul Grimault, next significant French animator