Winsor McCay facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Winsor McCay

|

|

|---|---|

Winsor McCay in 1906

|

|

| Born |

Zenas Winsor McKay

c. 1866–71 Spring Lake, Michigan, US; or Canada (disputed)

|

| Died | July 26, 1934 (aged 63–68) New York City, US

|

| Resting place | Cemetery of the Evergreens, Brooklyn, New York |

| Occupation |

|

|

Notable work

|

|

| Spouse(s) |

Maude Leonore McCay

(m. 1891–1934) |

| Children |

|

| Signature | |

|

|

Winsor McCay (born around 1866–71 – died July 26, 1934) was a famous American cartoonist and animator. He is best known for his amazing comic strip Little Nemo (1905–14; 1924–26). He also created the groundbreaking animated film Gertie the Dinosaur (1914). For a while, he used the pen name Silas for his comic strip Dream of the Rarebit Fiend.

From a young age, McCay was a very talented artist. He started his career drawing posters and performing live shows. In 1898, he began illustrating for newspapers and magazines. In 1903, he joined the New York Herald. There, he created popular comic strips like Little Sammy Sneeze and Dream of the Rarebit Fiend.

In 1905, his most famous strip, Little Nemo in Slumberland, appeared. It was a fantasy story about a young boy's adventurous dreams. The strip showed McCay's great drawing skills and his mastery of color. He often experimented with how the comic strip page looked. He changed the size and shape of panels to make the story more exciting. McCay also drew many detailed editorial cartoons. He was a popular performer who gave "chalk talks" on the vaudeville stage.

McCay was a true pioneer in animation. Between 1911 and 1921, he made ten animated films. Some of these films only exist in pieces today. His film Gertie the Dinosaur was special. It was an interactive show where McCay seemed to give orders to a trained dinosaur. He and his helpers worked for almost two years on his most ambitious film, The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918). This film showed the German torpedo attack on the RMS Lusitania in 1915. Later in his career, his animation and comic strip work slowed down. His employer, newspaper owner William Randolph Hearst, wanted McCay to focus on editorial illustrations.

McCay's drawings were known for their strong use of perspective. This was especially true in his detailed buildings and city scenes. He used many fine lines, called hatching, in his editorial cartoons. Color was a very important part of Little Nemo. McCay's comic strips have inspired many cartoonists and illustrators. The high quality of his animation was unmatched for many years. He invented techniques like inbetweening (drawing frames between main movements) and using registration marks. These methods became standard in animation.

Contents

Winsor McCay's Early Life and Career

Growing Up and Discovering Art

Winsor McCay's family came from Scotland. His grandparents moved to Canada in the 1830s. His father, Robert, was born in Canada. His mother, Janet, was also from a Scottish immigrant family. Robert and Janet married in 1866 and moved to Spring Lake, Michigan, in the United States.

There are no official records of McCay's birth. He once said he was born in 1869. His grave marker also shows this year. Later, he told friends he was born in 1871 in Spring Lake. Other records suggest 1866 or 1868. No Canadian birth record has been found. A fire in Spring Lake in 1893 might have destroyed any American records. His obituary said, "not even Mr. McCay knew his exact age."

McCay was known by his middle name, Winsor. He showed his drawing skills very early. He would draw anything he saw. People noticed how detailed and accurate his drawings were, even from memory. His father didn't think much of his art. He sent Winsor to a business college. But McCay often skipped classes. He would go to Detroit to draw portraits for money at museums.

McCay's talent soon got more attention. A drawing professor named John Goodison offered to teach him art privately. McCay eagerly accepted. Goodison taught him how to draw quickly and accurately. He also influenced McCay's use of color.

Starting His Professional Art Career

Around 1889, McCay moved to Chicago for two years. He worked on art for posters and pamphlets. In 1891, he moved to Cincinnati. There, he made posters and advertisements for dime museums. These were places where people could see interesting exhibits. In 1896, he saw Thomas Edison's Vitascope there. This was probably his first time seeing a film.

McCay's ability to draw quickly and accurately attracted crowds. People would watch him paint advertisements in public. In 1891, he met Maude Leonore Dufour at a museum. They soon married.

He started working part-time for the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune. In 1898, he got a full-time job there. His illustrations showed his bold use of perspective and hatchwork. Soon after, he also started working for Life magazine. In 1900, McCay moved to The Cincinnati Enquirer for a higher salary. He drew many pictures and became the head of the art department. He started using thicker lines around his characters. This became a unique part of his style.

McCay's Famous Comic Strips

From 1903 to 1911, McCay created many popular comic strips. In 1903, he moved to New York City to work for the New York Herald. He started by drawing illustrations and editorial cartoons.

His first ongoing comic strip was Mr. Goodenough, which began in 1904. His first popular comic strip was Little Sammy Sneeze. This strip was about a boy whose sneezes caused huge, funny disasters. It ran from 1904 to 1906.

McCay's longest-running strip was Dream of the Rarebit Fiend. It started in 1904 and was for adults. Characters would have strange, sometimes scary dreams. They would wake up blaming the Welsh rarebit they ate. This strip was so popular that a book collection was published in 1905. McCay used the pen name "Silas" for this strip.

By 1905, the McCays had moved to Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn in New York. It was an hour's commute from his office. But they thought it was a better place to raise their children. As his fame grew, he was allowed to work from his home studio more often.

The World of Little Nemo

In October 1905, McCay's masterpiece, Little Nemo in Slumberland, debuted. This full-page Sunday strip was about a child who had amazing dreams. Each week, the dream would end with him waking up in the last panel. Nemo's look was based on McCay's own son, Robert.

McCay was very creative with the layout of Little Nemo. He used different panel sizes and shapes. He also used perspective and detailed drawings of buildings. The Herald had the best color printing at the time. McCay would add notes to his Nemo pages with exact color instructions for the printers.

In 1906, McCay began performing "chalk talks" on the vaudeville stage. He would draw twenty-five sketches in fifteen minutes for live audiences. His first show was a big success. He toured with the show through 1907. He still managed to finish his comic strip and illustration work on time.

A big stage musical based on Little Nemo was created in 1907. It was very expensive to produce. The show was popular and toured for two seasons. McCay even brought his vaudeville act to each city where Little Nemo played.

Winsor McCay's Animation Breakthroughs

McCay said he was most proud of his animation work. He made ten animated films between 1911 and 1921.

McCay was inspired by the flip books his son brought home. He realized he could make his cartoons move. He claimed to be the first person to make animated cartoons. For his first animated short, he drew four thousand pictures of his Little Nemo characters. This film, simply called Little Nemo, first showed in movie theaters in April 1911. McCay then used it in his vaudeville act. He even hand-colored each frame of the film.

McCay was not happy with the Herald newspaper. In 1911, he accepted a better offer from William Randolph Hearst at the New York American. He took his Little Nemo characters with him. The Herald owned the copyright to the strip. But McCay won a lawsuit that let him keep using the characters. He renamed the strip In the Land of Wonderful Dreams.

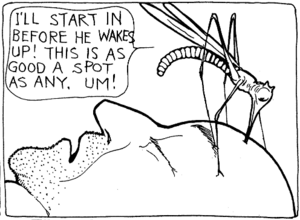

In May 1911, McCay started his next animated film, How a Mosquito Operates. It was based on a Rarebit Fiend episode. In the film, a giant mosquito drinks so much blood that it explodes. The animation was very realistic. The mosquito's body swelled naturally with each sip. The film was finished in January 1912.

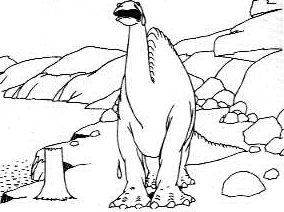

Gertie the Dinosaur first appeared in February 1914. It was part of McCay's vaudeville show. McCay introduced Gertie as "the only dinosaur in captivity." He would command the animated dinosaur with a whip. Gertie seemed to obey him, bowing to the audience. She would also eat a tree and a boulder. But sometimes she would rebel. When McCay scolded her, she would cry. He would then pretend to throw her an apple. A cartoon apple would appear on screen at the same time. In the end, McCay would walk off stage. Then, an animated version of him would appear in the film, and Gertie would carry him away.

Gertie was McCay's first animation with detailed backgrounds. He drew the characters. His neighbor, John A. Fitzsimmons, traced the backgrounds. McCay developed a system for drawing the frames in between main movements. This made the animation smoother. He did not patent his system. Another animator, John Randolph Bray, patented many of McCay's techniques. These included using registration marks and tracing paper. McCay later received payments from Bray for using these techniques.

Hearst, McCay's employer, was not happy with his newspaper work. He wanted McCay to stop his comic strip work and focus on editorial illustrations. Hearst also limited McCay's vaudeville shows. By February 1917, McCay had to give up all other paid work outside of Hearst's company. Hearst increased McCay's salary to make up for the lost income.

McCay was expected to report to the American building every day. He shared an office with other cartoonists. He illustrated editorials for Arthur Brisbane, who often asked for changes. The quality of his drawings depended on his interest in the topic.

McCay's next big film was The Sinking of the Lusitania. He started it in 1916. This film was not a fantasy. It was a detailed, realistic recreation of the 1915 German torpedo attack on the RMS Lusitania. This event killed 128 Americans and helped lead the U.S. into World War I.

McCay paid for Lusitania himself. It took almost two years to finish. He drew the film on sheets of cellulose acetate (called "cels"). This was the first time McCay used cels. Cels saved work because animators could draw moving parts on one layer and place them over a static background. This meant they didn't have to redraw the background for every frame. The film was very realistic. It used dramatic camera angles that would have been impossible in a live-action film.

The Sinking of the Lusitania was released in July 1918. It was advertised as a unique film. It also called McCay "the originator and inventor of Animated Cartoons." The film said it took 25,000 drawings to complete. It earned $80,000, but it didn't make a huge profit compared to McCay's investment.

McCay continued to make animated films using cels. By 1921, he had finished six more. Some of these only survive in pieces. In 1921, he released three films based on Dream of the Rarebit Fiend: Bug Vaudeville, The Pet, and The Flying House.

Later Years and Legacy

After 1921, McCay had to stop making animation. Hearst found out he was spending more time on animation than on his newspaper illustrations.

McCay's son, Robert, married in 1921. McCay bought them a house nearby. Robert had difficulty drawing after serving in World War I. McCay tried to help him by finding him cartooning work. Some of McCay's editorial cartoons were even signed "Robert Winsor McCay, Jr." Robert also briefly brought back the Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend strip in 1924.

In 1924, McCay left Hearst. He returned to the Herald Tribune and brought back Little Nemo. The new strip still showed his amazing drawing skills. But it was not as popular with readers. It ended in December 1926. Hearst executives convinced McCay to return to the American in 1927.

In 1927, McCay attended a dinner in his honor. Animator Max Fleischer introduced him. McCay gave advice to the animators there. But he also criticized them. He said, "Animation is an art. That is how I conceived it. But as I see, what you fellows have done with it, is making it into a trade. Not an art, but a trade. Bad Luck!" He often complained about the state of animation at the time.

Winsor McCay was healthy for most of his life. But on July 26, 1934, he had a severe headache. His right arm, his drawing arm, became paralyzed. He lost consciousness and passed away later that day. He died of a cerebral embolism. He was buried in Brooklyn.

McCay's Lasting Influence

After McCay's death, his son Robert tried to continue his father's legacy. He tried to bring back Little Nemo as a comic strip and a comic book. But neither project lasted long.

Much of McCay's original artwork was not saved well. He wanted his original drawings returned to him. A large collection of his work was destroyed in a fire in the late 1930s. His wife was unsure what to do with the remaining pieces. His son took them, but the family sold some when they needed money.

Many of McCay's original film cans were also destroyed. Much of his film has not survived. This is because it was made on nitrate film, which breaks down and is very flammable.

In 1966, cartoonist Woody Gelman found many original Little Nemo drawings. They were displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. His collection of McCay originals is now at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum.

McCay's work, with its realistic perspective, influenced films by Walt Disney. Disney honored McCay in 1955 on an episode of Disneyland. The episode showed a history of animation and recreated McCay's vaudeville act with Gertie. Disney told McCay's son, "Bob, all this should be your father's."

Many experts agree that McCay's influence on animation history is huge. Film critic Richard Eder compared McCay to early Renaissance artists. They were very skilled but had limited tools. McCay's strength was in his amazing visuals.

Italian filmmaker Federico Fellini was greatly influenced by Little Nemo. Comics historian R. C. Harvey called McCay "the first original genius of the comic strip medium" and in animation. He said that other artists at the time couldn't continue McCay's new ideas. So, it was left for future generations to rediscover them.

McCay's work has inspired many cartoonists, from Carl Barks to Art Spiegelman. Robert Crumb called McCay a "genius." Art Spiegelman's later work used some of McCay's images. Maurice Sendak's children's book In the Night Kitchen (1970) was a tribute to McCay.

The Winsor McCay Award was created in 1972. It honors people for their lifetime contributions to animation. The Hammer Museum in Los Angeles dedicated a room to McCay's work in 2005. A complete, full-size edition of Little Nemo was published in 2014.

An American astronomer named an asteroid 113461 after McCay in 2002. In Spring Lake, Michigan, a public park and historical marker honor McCay. The park is called Winsor McCay Park. There are plans for a large Gertie the Dinosaur statue and a bronze statue of McCay in the park.

McCay's Artistic Style

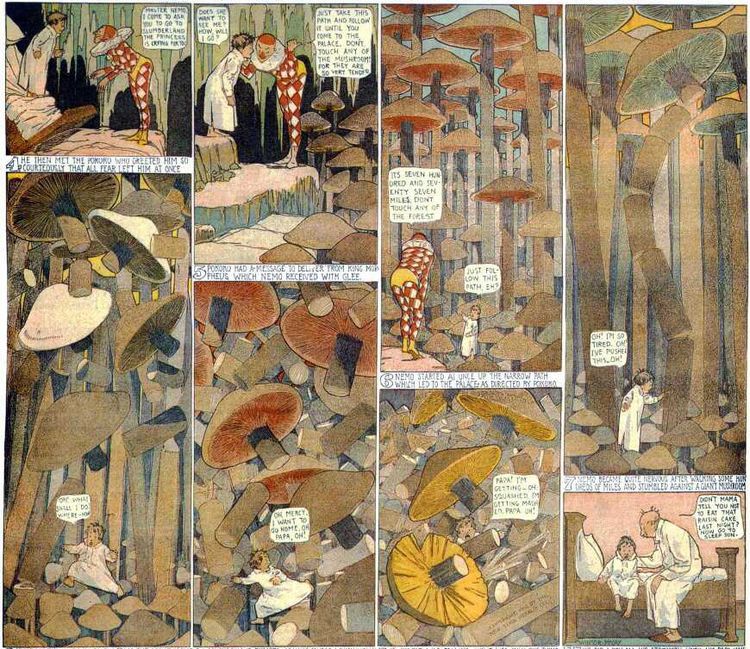

McCay was always trying new things with his art. He changed the size and shape of comic strip panels to create drama. For example, in an early Little Nemo strip, the panels grew bigger to show a growing forest of mushrooms. Few other cartoonists at the time were so bold with their page layouts.

McCay's detailed hatching and mastery of perspective made his drawings look very real. He was known for how fast and accurately he could draw. Crowds would gather to watch him paint billboards.

McCay loved ornate details. The buildings he drew were inspired by carnivals and the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. He also got ideas from detailed illustrations in British newspapers.

McCay's drawings had "absolute precision of line." He used black drawing ink and special pens. In his early magazine cartoons, he often painted with gouache.

McCay sometimes used self-reference in his work. This was most common in Dream of the Rarebit Fiend. He would sometimes put himself in the strip. Or characters would talk directly to the reader. Sometimes characters even knew they were in a comic strip!

In contrast to his amazing artwork, the words in McCay's speech balloons were sometimes hard to read. They often contained repeated phrases showing how upset the characters were. This showed that McCay's main talent was in visuals, not words.

McCay's comics and animation sometimes used common stereotypes of his time. For example, he showed black characters as savages. In Little Nemo, the white Nemo was drawn in a dignified style. He controlled the more exaggerated characters, Flip (an Irishman) and Little Imp (an African character). Women were not often seen in McCay's work. When they were, they were shown as superficial or argumentative.

Winsor McCay's Works

Comic Strips

| Title | Start Date | End Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A Tale of the Jungle Imps by Felix Fiddle | Jan 11, 1903 | Nov 9, 1903 | Based on poems by George Randolph Chester |

| Mr. Goodenough | Jan 21, 1904 | Mar 4, 1904 | |

| Sister's Little Sister's Beau | Apr 24, 1904 | Apr 24, 1904 | |

| Phurious Phinish of Phoolish Philipe's Phunny Phrolics | May 28, 1904 | May 28, 1904 | |

| Little Sammy Sneeze | Jul 24, 1904 | Dec 9, 1906 | |

| Dream of the Rarebit Fiend | Sep 10, 1904 | Jun 25, 1911 | |

| Jan 19, 1913 | Aug 3, 1913 | Revived by the New York Herald | |

| The Story of Hungry Henrietta | Jan 8, 1905 | Jul 16, 1905 | |

| A Pilgrim's Progress By Mister Bunion | Jun 26, 1905 | May 4, 1909 | Appeared in the New York Evening Telegram |

| Little Nemo in Slumberland | Oct 15, 1905 | Jul 23, 1911 | From 1911–14, it was called In the Land of Wonderful Dreams |

| Aug 3, 1924 | Dec 26, 1926 | Restarted after McCay returned to the Herald Tribune | |

| Poor Jake | 1909 | 1911 | Appeared in the New York Evening Telegram |

| In the Land of Wonderful Dreams | Sep 3, 1911 | Dec 26, 1914 | Little Nemo was renamed when McCay moved to Hearst's papers |

| Rarebit Reveries | c. 1923 | c. 1925 | A revival of Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, likely drawn by McCay |

| Title | Start Date | End Date | Notes |

Animated Films

| Title | Year | Notes | File |

|---|---|---|---|

| Winsor McCay, the Famous Cartoonist of the N.Y. Herald and His Moving Comics | April 11, 1911 | More commonly known as Little Nemo | |

| How a Mosquito Operates | January 1912 | Also known as The Story Of A Mosquito | |

| Gertie the Dinosaur | February 18, 1914 | The original stage show version is lost | |

| Winsor McCay, the Famous Cartoonist, and Gertie | December 28, 1914 | An expanded version of the stage show, with a live-action intro | |

| The Sinking of the Lusitania | May 18, 1918 | ||

| Bug Vaudeville | September 12, 1921 | ||

| The Pet | September 19, 1921 | ||

| The Flying House | September 26, 1921 | ||

| The Centaurs | 1921 | Only fragments of this film survive | |

| Gertie on Tour | c. 1918–21 | Only fragments of this film survive | |

| Flip's Circus | c. 1918–21 | Only fragments of this film survive | |

| Performing Animals | unknown | The original film has not survived | |

| Title | Year | Notes | File |

Images for kids

-

McCay grew up in Spring Lake, Michigan (red in left blowup of Ottawa County)

-

Nemo's bed takes a walk in the July 26, 1908, episode of Little Nemo in Slumberland.

-

The most successful of McCay's comic strips was Little Nemo

September 9, 1907 -

The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918) required 25,000 drawings to be made over two years, and was McCay's first film to use acetate cels.

-

In 1927, McCay expressed his disappointment at the state of the animation industry at a dinner in his honor, where he was introduced by Max Fleischer (pictured).

-

McCay's drawing for the Little Nemo strip running October 14, 1906, is in the collection of the National Gallery of Art.

-

Walt Disney acknowledged his debt to McCay's example.

-

McCay experimented with the formal elements of his strips, as when he had panels grow to accommodate a growing mushroom forest in a Little Nemo episode for October 22, 1905.

See also

In Spanish: Winsor McCay para niños

In Spanish: Winsor McCay para niños

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |