369th Infantry Regiment (United States) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 15th New York National Guard Regiment369th Infantry Regiment |

|

|---|---|

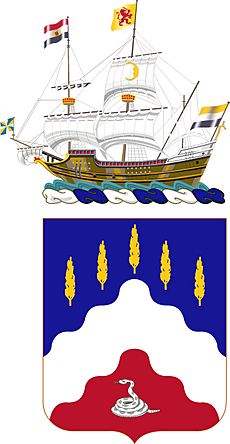

Coat of arms

|

|

| Active | 2 June 1913-present (369th Sustainment Brigade) 15 May 1942-3 February 1946 (AUS) |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Regiment |

| Nickname(s) | Hell-fighters, Men Of Bronze, Black Rattlers |

| Motto(s) | "Don't Tread On Me, God ..., Let's Go" |

| Engagements | World War I |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

William Hayward (American attorney) Benjamin O. Davis Sr. |

| Insignia | |

| DUI |  |

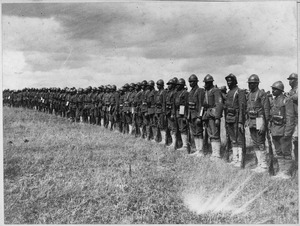

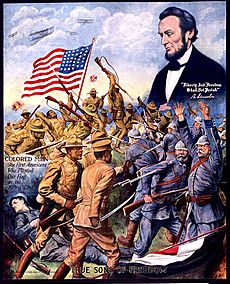

The 369th Infantry Regiment was an important army unit during World War I and World War II. It was first called the 15th New York National Guard Regiment. Later, it became known as the Harlem Hellfighters. Most of the soldiers in this regiment were African Americans. It also included men from places like Puerto Rico, Cuba, and other countries. White officers led the regiment. The 369th was one of the first African-American regiments to fight with the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I.

When they arrived in France, their commander, Colonel William Hayward, nicknamed them the Black Rattlers. The French soldiers called them Men of Bronze (Hommes de Bronze). This was because they saw how brave the Americans were in battle. It's said that the German enemy called them Hellfighters (Höllenkämpfer). However, this nickname might have been created by the American newspapers.

During World War I, the 369th spent 191 days fighting on the front lines. This was more than any other American unit. They also had the most soldiers injured or killed, with 1,500 casualties. The regiment was the first Allied force to cross the Rhine River into Germany.

Contents

Why the Harlem Hellfighters Were Formed

In 1917, Emmett Jay Scott became a special advisor to the Secretary of War. His job was to help with issues affecting African Americans in the war. Many African Americans hoped that fighting in the war would end unfair treatment at home. Sadly, this did not happen. After World War I, unfair treatment of African Americans was still very bad.

Many African Americans wanted to join the military. But they were often turned away. When the United States needed more soldiers, it passed the Selective Service Act of 1917. This law required all men aged 21 to 30 to register for the draft, including African Americans. Many joined, hoping their service would earn them respect from white Americans.

The 369th Regiment was formed from the 15th Regiment in New York. This state militia unit had helped during the 1863 New York City draft riots. It was officially reformed in 1913. When the U.S. entered World War I, many African Americans felt that joining the army was a chance to prove themselves. They believed it would help end unfair treatment. A special training camp was set up to train black officers for these new black regiments.

World War I Service

Becoming a Fighting Unit

The 369th Infantry Regiment officially started on June 2, 1913, in the New York Army National Guard. It was first called the 15th New York Infantry Regiment. The unit was fully organized on June 29, 1916, in New York City.

The regiment was called into federal service on July 25, 1917, at Camp Whitman, New York. Here, they learned basic military skills. After this training, they were sent to guard rail lines and construction sites around New York.

On October 8, 1917, the regiment moved to Camp Wadsworth in Spartanburg, South Carolina. Here, they trained for real combat. Camp Wadsworth was designed to look like French battlefields. However, while there, the soldiers faced a lot of unfair treatment because of their race. This came from local people and other army units.

In one event, Lieutenant James Reese Europe and Noble Sissle were not allowed to buy a newspaper at a hotel shop. White soldiers from another New York unit, the 27th Division, came to support them. Lieutenant Europe told them to leave to avoid a fight. Many other shops also refused to serve the 15th Regiment. The white soldiers then told these shop owners that if they didn't serve black soldiers, they should close their stores. They said, "They're our buddies. And we won't buy from men who treat them unfairly."

The 15th Infantry Regiment was assigned to the 185th Infantry Brigade in December 1917. Colonel William Hayward led them. The regiment left New York on December 27, 1917, and arrived in France. Even though they were trained as infantry, they were first given labor jobs instead of combat roles.

On March 1, 1918, the 15th Infantry Regiment was renamed the 369th Infantry Regiment. But they still did labor work while waiting for a decision about their future.

Fighting with the French Army

On April 8, 1918, the U.S. Army decided to assign the 369th to the French Army. This was because many white American soldiers refused to fight alongside African-Americans. The 369th soldiers were given French weapons, helmets, and gear, but they kept their U.S. uniforms.

In the United States, the 369th Regiment faced a lot of unfair treatment. But in France, they were treated like any other French unit. The French army had many non-white soldiers from their colonies. They also needed more soldiers, so they were less concerned about race than the Americans.

The 369th Infantry Regiment joined the French 16th Division on May 8, 1918. They fought continuously until July 3. They returned to combat in the Second Battle of the Marne. Later, they joined the French 161st Division for an Allied counterattack. They served on the front lines for over six months, which was the longest of any unit in World War I.

While overseas, the Hellfighters saw enemy messages trying to turn them against the U.S. These messages claimed Germans had done nothing wrong to black people. They said the soldiers should fight the USA, which had treated them badly for years. But these messages had the opposite effect.

On September 25, 1918, the French 4th Army attacked alongside the American forces in the Meuse–Argonne. The 369th fought bravely and captured the important village of Séchault. At one point, the 369th advanced faster than the French troops next to them. This put them at risk of being cut off. When the regiment finally pulled back, they had moved forward 14 kilometers (about 8.7 miles) through strong German resistance.

In mid-October, the regiment moved to a quiet area. They were there on November 11, the day the war ended. Six days later, the 369th made its last advance. On November 26, they reached the banks of the Rhine river. This made them the first Allied unit to do so. The regiment returned to New York and was officially disbanded on February 28, 1919. They then rejoined the New York Army National Guard.

Honors and Recognition

One Medal of Honor and many Distinguished Service Crosses were given to soldiers in the regiment.

One of the most famous soldiers was Private Henry Johnson. He was a porter from Albany, New York. He earned the nickname "Black Death" for his bravery in France. In May 1918, Johnson and Private Needham Roberts fought off a 24-man German patrol. Both were badly wounded. Johnson told Roberts to warn the French units. But Roberts came back after the Germans started shooting at them. They fought together until a German grenade hurt Roberts. Then, Johnson fought alone to protect his friend. After running out of bullets, Johnson used grenades, then his rifle butt, and finally a bolo knife. Reports say Johnson killed at least four German soldiers and may have wounded 30 others. He himself was injured at least 21 times. Johnson was the first American to receive the Croix de Guerre, a French award for bravery.

On December 13, 1918, the French government gave the Croix de Guerre to 170 members of the 369th. The entire regiment also received a unit award. General Lebouc pinned it to their flag.

The 369th was one of the first U.S. army units to have black officers and all-black enlisted men. They had a great combat record and many awards from the French government. However, the constant fighting and lack of rest made the unit very tired by the end of the war.

The 369th Infantry Regiment was the first New York unit to return home. On February 17, 1919, they marched up Fifth Avenue in New York City. This day became a special holiday for Harlem. Thousands of people, including many black schoolchildren, lined the streets to see them. The parade became a symbol of African American service to the nation. It was often mentioned by those fighting for civil rights.

Arthur W. Little, a commander in the regiment, wrote in their history book From Harlem to the Rhine: The unit was under fire for 191 days. They never lost any ground or had a man taken prisoner. Only once did they fail to reach their goal, and that was due to problems with French artillery support.

By the end of World War I, the 369th Infantry had fought in several major campaigns. They suffered 1,500 casualties, the highest of any U.S. regiment. The unit also faced problems with discipline because so many experienced soldiers were lost. The 369th also fought in famous battles like Belleau Wood and Chateau-Thierry.

The 369th Regiment Military Band

The 369th Regiment "Hellfighters Band" was important for boosting morale. By the end of their time in Europe, they became one of the most famous military bands. They introduced a new type of music called jazz to British, French, and other European audiences.

After the war, the 369th returned to New York City. On February 17, 1919, they had a parade through the city. This day became an unofficial holiday in Harlem. Many black schoolchildren were let out of school to watch. Thousands of people lined the streets to see the 369th Regiment. The parade started on Fifth Avenue and marched into Harlem. Black New Yorkers filled the sidewalks to cheer them on. This parade became a symbol of African American service to the nation. It was often used when people campaigned for civil rights.

Later Years and Legacy

In 1924, the regiment was reorganized as the 369th Coast Artillery (Antiaircraft) Regiment. They were sent to Hawaii and parts of the West Coast. In 1941, they were called into federal service again.

In 1942, the 369th Infantry Regiment was re-established for World War II. This new unit was part of the 93rd Infantry Division. They worked on labor and security tasks in the Southwest Pacific. They occupied Morotai in Dutch New Guinea from April to June 1945, seeing limited fighting. The unit was deactivated in 1946.

The 369th Regiment Armory

In 1933, the 369th Regiment Armory was built to honor the 369th regiment. This building stands at 142nd Street and Fifth Avenue in Harlem. It was completed in the 1930s. The armory is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is a city landmark.

Continuing Recognition

The reputation of the infantry after World War I was sometimes challenged due to ongoing racial tension. In 1940, a newspaper reported that the U.S. Department of War planned to rename the 369th regiment the "Colored Infantry." The department also said that the 369th might be removed from the National Guard. Supporters quickly protested against adding racial identity to the unit's name. This helped protect the regiment's reputation. However, eventually, all African American U.S. Army units were renamed "Colored." The 369th served in World War II as the 369th Coast Artillery Regiment (Antiaircraft) (Colored).

In 2003, the Harlem River Drive was renamed the "Harlem Hellfighters Drive." On September 29, 2006, a 12-foot-high monument was unveiled to honor the 369th Regiment. This statue is a copy of a monument in France. It is made of black granite and has the 369th crest and rattlesnake symbol.

Units that came from the 369th Infantry Regiment have continued to serve. The 369th Infantry Regiment served until World War II. It was then reorganized into the 369th Anti-aircraft Artillery Regiment. This new regiment served in Hawaii and on the West Coast. Today, the 369th has been reformed into the 369th Sustainment Brigade.

In August 2021, the regiment received the Congressional Gold Medal. This award recognized their bravery and excellent service during World War I.

Famous Soldiers

- Benjamin O. Davis Sr.

- James Reese Europe

- Hamilton Fish III

- Henry Johnson

- Rafael Hernández Marín

- Horace Pippin

- Needham Roberts

- Noble Sissle

- Vertner Woodson Tandy

- John Woodruff

Unit Symbols

The unit's symbol is a silver metal and enamel design, about 1 and 1/4 inches tall. It shows a blue shield with a silver rattlesnake coiled and ready to strike.

The rattlesnake is a symbol used on some early American flags. It is linked to the original thirteen colonies. The silver rattlesnake on the blue shield was the special symbol of the 369th Infantry Regiment. It represents the unit's service during World War I.

This symbol was first approved for the 369th Infantry Regiment on April 17, 1923. It has been used by different units that came from the 369th over the years.

369th Veterans' Association

The 369th Veterans' Association is a group created to honor those who served in the 369th infantry. This group has three main goals:

- To promote friendship and goodwill among its members.

- To take part in social and community activities that help its members.

- To remember the patriotic service of its members in the 369th and other U.S. Armed Forces units.

Harlem Hellfighters in Media

The 2014 graphic novel The Harlem Hellfighters by Max Brooks tells a fictional story about the 369th's time in Europe during World War I. A film based on this novel is being made by Sony Pictures.

In 2018, the 369th Infantry Regiment was featured in the documentary Noble Sissle's Syncopated Ragtime. This film is about the musician and Harlem Hellfighters soldier Noble Sissle. It won Best US Documentary Feature Film at the 2019 American Documentary Film Festival.

The Swedish power metal band Sabaton also dedicated a song to the Harlem Hellfighters on their 2022 album The War to End All Wars.

See also

In Spanish: 369.º Regimiento de Infantería (Estados Unidos) para niños

In Spanish: 369.º Regimiento de Infantería (Estados Unidos) para niños

- 369th Sustainment Brigade (United States)

Images for kids

-

Emmett Jay Scott helped create the Hellfighters.