Horace Pippin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Horace Pippin

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | February 22, 1888 |

| Died | July 6, 1946 (aged 58) |

| Resting place | Chestnut Grove Cemetery Annex, West Chester, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Painting |

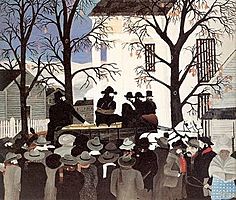

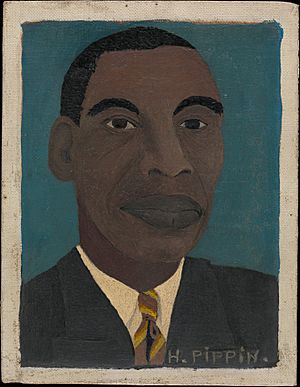

Horace Pippin (born February 22, 1888 – died July 6, 1946) was an American artist. He taught himself how to paint. Horace Pippin created many types of art. He painted scenes from his time in World War I, landscapes, and portraits. He also painted pictures about the Bible.

Some of his most famous paintings show the history of slavery and racial segregation in the U.S. He was the first Black artist to have a book written just about his art. This book was called Horace Pippin, A Negro Painter in America (1947). The New York Times newspaper called him the "most important Negro painter" in American history. He is buried in West Chester, Pennsylvania. A special marker shows where he lived and honors his achievements.

Contents

Horace Pippin's Early Life

Horace Pippin was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, on February 22, 1888. His mother was Harriet Pippin. He grew up near Goshen, New York. Later, he moved back to West Chester.

In Goshen, he went to schools that were separated by race. He left school at age 15 to help his sick mother. As a boy, Horace won an art contest. He received his first crayons and watercolors. He loved to draw racehorses and jockeys from Goshen's famous racetrack. Before joining the army, Pippin worked different jobs. He was a hotel porter, a furniture packer, and an iron moulder. In 1920, Pippin married Jennie Fetherstone Wade Giles. She had a six-year-old son from a previous marriage.

Serving in World War I

In World War I, Pippin joined the K Company. This was part of the 369th Infantry Regiment. They were known as the brave Harlem Hellfighters. This army unit was mostly Black soldiers. They faced unfair treatment in the U.S. Army because of segregation. Later, they were put under the command of the French Army.

The Harlem Hellfighters were on the war's front lines longer than any other U.S. regiment. They fought almost constantly from April until the war ended. The entire regiment received the French Croix de Guerre award for their bravery. In September 1918, a German sniper shot Pippin in his right shoulder. This injury made it hard for him to use his arm. He was honorably discharged from the army in 1919. In 1945, he received a Purple Heart medal for his injury.

Pippin described his war experience:

I did not care what or where I went. I asked God to help me, and he did so. And that is the way I came through that terrible and Hellish place. For the whole entire battlefield was hell, so it was no place for any human being to be.

After the war, Pippin wrote four memoirs. One of them had illustrations. These books described his difficult time in the military. He continued to paint war scenes throughout the 1930s and 1940s. He said that World War I "brought out all the art in me."

- Horace Pippin's War Notebooks, ca. 1920

Horace Pippin's Art Career

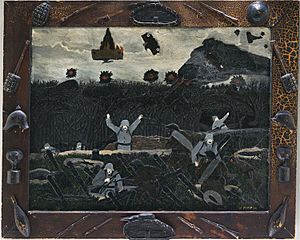

Pippin started making art in the 1920s. Some say he did this to help his injured arm heal. He began painting on canvas in 1930 with his work The Ending of the War: Starting Home. He explained how he created his art: "The pictures which I have already painted come to me in my mind, and if to me it is a worth while picture, I paint it."

He painted many different subjects. These included landscapes, still lifes, and scenes from the Bible. He also made paintings with political messages. Some of his works were based on his own experiences in the war. Others showed everyday life from the early 1900s.

Becoming a Famous Artist

Pippin became known when he showed two paintings at a local art show. This was the Chester County Art Association (CCAA) Annual Exhibition. People like art critic Christian Brinton and artist N. C. Wyeth encouraged him. Brinton quickly set up a solo show for Pippin. This show was supported by the CCAA and the West Chester Community Center.

Brinton also connected Pippin with important art curators. By 1940, Pippin was working with art dealer Robert Carlen and collector Albert C. Barnes. Pippin even took art classes at the Barnes Foundation in 1940. Carlen, Barnes, and later dealer Edith Halpert helped Pippin's career a lot.

Pippin's fame grew quickly across the country and even internationally. This happened in the eight years between his first national show in 1938 and his death at age 58. He had solo exhibitions in Philadelphia (1940, 1941) and New York (1940, 1944). His art was also shown at the Arts Club of Chicago (1941) and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (1942).

Museums like the Barnes Foundation, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art bought his paintings. His works were also featured in major art shows. Art critic Alain LeRoy Locke described Pippin as "a real and rare genius." He said Pippin combined folk art with artistic skill in a unique way.

Horace Pippin's Artworks

Pippin's art includes many different subjects and styles. In the 1920s, he started by burning designs into wood panels. These were mostly snow scenes. He would then add one or two colors of paint to highlight parts of the image.

His first oil painting was The Ending of the War, Starting Home (1930–1933). It shows a scene from his experience at the Battle of Sechault, where he was shot. He also made the frame for this painting. He decorated it with hand-carved war items, like helmets and weapons. He painted about World War I several more times in the 1930s and again in 1945.

Religious and Historical Paintings

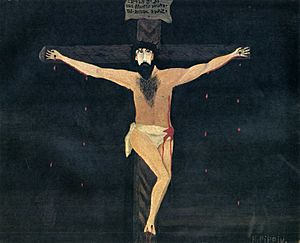

Pippin painted several religious subjects. Some showed scenes from the Bible. Others were more imaginative, like his Holy Mountain series. He was a religious man. He taught Sunday school and sang in his church choir.

His Holy Mountain series is very famous. These three paintings are like the Peaceable Kingdom paintings by Quaker artist Edward Hicks. Hicks's paintings show predators and prey living together peacefully. Pippin added parts from his own time to show that peace and conflict are often close. The backgrounds of his paintings include soldiers, graveyards, war planes, and bombs. These contrast with the peaceful scenes in the front.

In The Knowledge of God and The Holy Mountain III, Pippin addressed lynching. This was a terrible act of violence against Black people in the segregated southern United States. He connected ideas of destruction and peace by writing important World War I dates on each painting.

- The Holy Mountain I has "June 6, 1944" (D-Day).

- The Knowledge of God has "Dec. 7 1944" (anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor).

- The Holy Mountain III has "Aug 9, 1945" (when the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki).

Some people think the shepherd in the middle of these paintings looks like Pippin himself.

Pippin painted two self-portraits. One shows him sitting at his easel. His painting John Brown Going to his Hanging (1942) is about the abolitionist who helped start the Civil War. It is part of a series of three paintings about John Brown.

Mr. Prejudice and Everyday Life

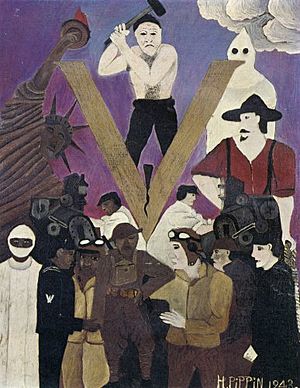

Mr. Prejudice was painted in 1943 during World War II. It was made for someone who asked for it. This painting is special because of its unique design and symbols. It is a small painting, about the size of a magazine cover. It shows figures separated by race.

On the bottom left, there are Black soldiers, a medic, and a factory worker. Most of them face the viewer. A brown-skinned figure in an old World War I uniform might be Pippin himself. On the bottom right, there are white men. They mostly turn to the left.

At the top, a white man uses a sledgehammer to drive a wedge into a large "V." This "V" stands for "V for Victory" in World War II. African Americans created the "Double V" campaign. They wanted victory in the war abroad and victory over racism at home. On the top left, a large, brown-skinned Statue of Liberty holds her torch. This lights the way to freedom. On the top right, a lighter-skinned figure in red holds a noose. He stares at Lady Liberty. A hooded Ku Klux Klansman is above him.

Pippin's genre paintings show scenes from everyday life. These are very popular. Examples include Domino Game (1943) and several versions of Cabin in the Cotton. Some paintings, like After Supper (around 1935–1939) and The Milkman of Goshen (1945), show his childhood in New York State. Before the Great Migration, scenes of Black families' daily lives were not often seen by white people. Pippin's paintings offered a special look into these lives.

Pippin also made art about popular culture. This included Old Black Joe, based on the song, and Uncle Tom, based on the novel Uncle Tom's Cabin. He painted two portraits of the famous Black singer Marian Anderson. He also dedicated a painting to Paul Robeson.

Pippin left The Park Bench unfinished when he died in 1946. Artist Romare Bearden later said that the man in the painting might be Pippin himself. He said Pippin had finished his life's journey and was sitting alone, thoughtfully, in the autumn of his life.

Collections and Exhibitions

Horace Pippin painted about 140 works. Many of these are in museum collections. Some of these museums include:

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

- Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

- Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA

- Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA

- The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, PA

- the Brandywine River Museum, Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania

- The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

- Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA

Horace Pippin was the first African American artist to have a book written only about his art. This book was Selden Rodman's Horace Pippin: A Negro Painter in America from 1947. Since then, he has had three major exhibitions that showed many of his works. Several books, articles, a book of poetry, and children's books have also been written about him.

- Horace Pippin. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C., February 25–March 1977; Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York, April 5–30, 1977; and Brandywine River Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, Pa., June 4–September 5, 1977.

- I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, January 21–April 17, 1994; Art Institute of Chicago, April 30–July 10, 1994; Cincinnati Art Museum, July 28–October 9, 1994; Baltimore Museum of Art, October 26, 1994 – January 1, 1995; and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 1–April 30, 1995.

- Horace Pippin: The Way I See It. Brandywine River Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, Pa., April 25–July 19, 2015

See also

In Spanish: Horace Pippin para niños

In Spanish: Horace Pippin para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |