Adeline Knapp facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Adeline E. Knapp

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | March 14, 1860 Buffalo, New York |

| Died | June 6, 1909 (aged 49) San Francisco, California |

| Occupation |

|

Adeline E. Knapp (March 14, 1860 – June 6, 1909) was an American journalist, author, and social activist. She was also an environmentalist and an educator. Knapp was a well-known figure in the San Francisco Bay Area's writing community around the year 1900.

She was a bold writer who often wrote about important topics in her newspaper columns for The San Francisco Call. Knapp covered many subjects, from farm animals to the annexation of Hawaii. She supported causes like stopping child labor and protecting nature (called conservation). However, she also had some views that were not common for her time. For example, she expressed Anti-Chinese sentiments and had doubts about the women's suffrage movement. While many American women wanted the right to vote, Knapp spoke against it in New York state hearings. Her speeches were even used by groups that opposed women's voting rights.

Knapp also wrote many short stories and a novel set in the Arizona desert. These stories showed her love for the outdoors and her sharp mind. They also reflected her interest in the American West. Although her works were praised when she was alive, they are not widely read today.

Contents

Early Life and Writing Beginnings

Adeline Knapp was born on March 14, 1860, in Buffalo, New York. Her parents were Lyman and Adeline Knapp. She was one of nine children in her family. To tell her apart from her mother, Adeline was called "Dellie" as a child. Later, her friends and family knew her as "Delle."

From a young age, Knapp loved writing. At just eight years old, she wrote poems and stories for her friends. By age 14, she published her own writings. She even started her own newspaper, The Queen City Enterprise, at 14. This monthly paper lasted almost two years, giving her a first taste of journalism. It was a big achievement for a young woman at that time. She also published another paper called Aspirant in Buffalo and became known as a poet. In 1877, she joined the National Amateur Press Association. Although she thought about becoming a doctor, her family believed she would become a journalist.

Her father, Lyman Knapp, was a respected businessman in Buffalo. He worked in the grocery business and later in distilling. He was also a senior member of a brokerage firm. Mr. Knapp was involved in the Volunteer Fire Department and helped start the Fireman's Benevolent Association. He also helped organize the first Water Works Company. Her family was financially secure.

Knapp's parents taught their children to work hard. By age 17, Adeline felt ready to start her own career. She began working in a large store for seven years, putting her journalism aside. However, at 24, she became an associate editor for the Buffalo Christian Advocate newspaper. While working at the Advocate, Knapp also studied medicine at the University at Buffalo. She studied for three years before deciding to move to California.

Life in California and Journalism

In 1887, Knapp moved from Buffalo to San Francisco. She joined the staff of The San Francisco Call newspaper. There, she created the paper's Woman's Department, which became very popular.

While still working for the Call, she bought a weekly newspaper called the Alameda County Express. She became a country editor and publisher, doing many jobs herself. She was the editor, business manager, advertising agent, and even the delivery person. After about a year and a half, she combined the Express with the Oakland Daily Tribune.

After the merger, she worked for the Call as a foreign exchange editor. When the newspaper discovered her knowledge of horses and cattle, she moved to the livestock department. She wrote a weekly article about horses and cattle under the pen name "Miss Russell." She also wrote other stories under her own name.

Knapp became an important part of the San Francisco Bay Area's writing community. She was especially active in the East Bay area, where she met writers like Joaquin Miller and Ina Coolbrith.

During her time in California, she became interested in women's issues. She spent much of her free time with the San Francisco Woman's Educational and Industrial Union. This group worked to unite women across the United States to support women's voting rights. For about ten years, she strongly supported women in business, women's right to vote, and equal rights for men and women. However, her ideas changed around the year 1900.

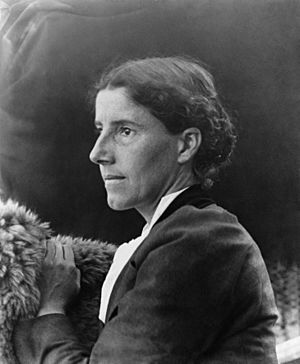

Adeline Knapp and Charlotte Perkins Gilman

In April 1891, Knapp met the writer Charlotte Perkins Stetson (who later became Charlotte Perkins Gilman). Gilman had recently moved to California after separating from her husband. The two women quickly became close friends. In September, they began living together.

Gilman wrote about Knapp in her autobiography, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. She said that she was happy to have "some one to love me, and whom I love."

By 1893, their friendship became difficult. Gilman's diaries show that their relationship was in trouble. On May 11, she wrote: "All along lately hard times with Delle." The next day, she noted a "Dreadful time with Delle." By May 14, they decided to live separately. Knapp stayed for two more months before moving out in July.

In her autobiography, Gilman described the end of their friendship in strong terms. She wrote that Knapp was a "literary vampire" who would copy other authors' styles. Gilman also suggested that Knapp spread false rumors about her.

International Reporting and Education

In the early 1890s, Knapp's work on horses and cattle changed to more important international reporting. In 1893, she traveled to Hawaii to cover the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom. She was likely the first woman newspaper reporter to cover such a major event.

Knapp's reports from Hawaii often appeared on the front pages of the Call. On March 9, a long article by Knapp, dated March 1, was titled "Hawaii's Hope." It covered the entire front page and part of the second page. This was about six weeks after the peaceful overthrow of Queen Liliuokalani. Knapp noted that a visitor might not even realize there had been a big change.

Knapp described the palace being prepared for the new government. Belongings of the former royal family were being moved out. She wrote that these "relics of departing royalty presented a touching spectacle."

While Knapp felt some sadness for the deposed queen, she believed that native Hawaiians did not truly want annexation by the United States. She thought they might prefer an American protectorate. However, she also felt that some foreign power would eventually control the country. She argued that the United States had the most to gain or lose. Knapp believed that if another major power, like Great Britain, controlled Hawaii, it would be a threat to the United States.

After her visit to Hawaii, Knapp traveled to the Far East. She wrote about her journeys to Yokohama in Japan and Manila in the Philippines.

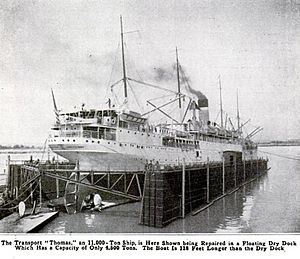

After the Spanish–American War, Knapp moved from San Francisco to the Philippines. She was one of about a thousand American teachers, known as Thomasites. They traveled on the ship U.S. Army Transport Thomas to teach in the new Filipino schools.

In 1902, Knapp wrote a history book about the Philippines. It covered Philippine history from Magellan's discovery to the arrival of the Americans. Her book was the first history of the Philippines written for school children. She said she wrote it to make the country's history understandable for young readers.

Social Activism and Environmentalism

Knapp was involved in many social causes and reform movements, both in her journalism and personal life.

One of her efforts was a series of stories in 1892 called "Two Chums: Sketches from Life." These stories, published in the San Francisco Call, showed the terrible effects of child labor. They told a sad story of two young jute mill workers who died tragic deaths. Their deaths were hardly noticed. These articles were praised by The Woman's Column, a publication of the American Woman Suffrage Association. They noted that Knapp's stories helped raise public awareness against using children in factories.

Knapp was also an active environmentalist. The San Francisco Call called her "California's naturalist at large" in 1897.

In the mid-1890s, Knapp wrote many articles about nature for the Call. For example, "The Blessed Hills of San Francisco" suggested that walking the city's hills could give people a better view of their city life. Her book Upland Pastures, published in 1897, was a collection of her nature writings. Another collection, In the Christmas Woods, came out in 1899.

In 1899, Knapp wrote to John Muir, a famous naturalist. She asked for his help in fighting against the killing of birds for their plumes (feathers) used in hats. She hoped to get women's clubs to take action. Knapp asked Muir to write a few lines for an article with interviews from bird lovers. She noted that "The milliners say that not in 20 years have birds been used for trimming as they are this winter." She felt they needed to act quickly to make a difference.

Views on Race and Immigration

Adeline Knapp's views on race and immigration have been discussed in recent years. Some scholars believe she held views that were against Asian immigration. For example, her 1895 story, "The Ways That Are Dark," has been seen as promoting anti-Chinese ideas. During the years Knapp lived with Gilman, there was strong anti-Chinese feeling in California. Laws were passed to limit and deport Asian immigrants.

However, Knapp also admired the Japanese writer Yone Noguchi. She wrote several articles supporting his work and making it known to others.

Knapp's views on Filipinos can be found in her 1902 history textbook for Filipino students, The Story of the Philippines. Most of her book focuses on European colonization of the islands. She briefly mentioned two "wild tribes," the Negritos and Igorotes, distinguishing them from the "civilized Filipino people" who were part of the Malay race. She described the Negritos as "small, timid people" who were "dying out." She wrote that the Igorots were "the finest and strongest of all the wild tribes" and were "very brave." She described the Malays as "sea-going folk, daring sailors, and skillful in managing their boats."

Opposition to Women's Voting Rights

Over the years, Knapp and Gilman shared many interests and opinions. But on one important issue, they disagreed. Both women initially supported equal rights for women. However, Knapp later changed her mind about women's voting rights. She began to question and oppose giving women the right to vote and run for political office.

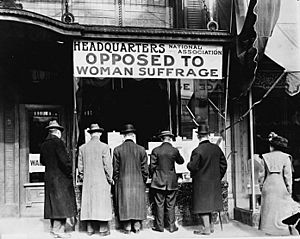

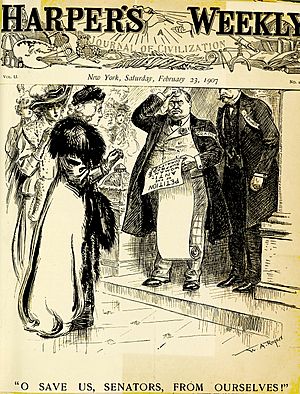

At a time when many American women were fighting for more rights, Knapp spoke out against the suffrage movement. She spoke before the Senate and Assembly Judiciary Committee of the New York State Legislature. Her views were published in pamphlets by the New York State Association Opposed to the Extension of Suffrage to Women. This group was founded in 1897. Knapp's writings were used as propaganda by this group.

The San Francisco Call once published a column, supposedly by Knapp, that said women were controlled by men because of economic dependence, not because they couldn't vote. It stated, "As long as they depend on men for their bread and butter, they will be under the orders of men."

By 1899, Knapp's lack of interest in suffrage had turned into strong opposition. To support her new stance, she wrote "An Open Letter to Mrs. Carrie Chapman Catt." This letter was printed by the New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. In it, Knapp questioned whether women truly needed "the ballot," or the right to vote. She argued for women to focus on "the inner things of the home and of society." This letter was written after a conference where Carrie Chapman Catt spoke about women's full suffrage.

For a few years in the early 1900s, Knapp edited the Household Magazine in New York. During this time, she kept in touch with Gilman. Later, when both lived in New York, Gilman was campaigning for women's voting rights. Knapp, however, gave opposing testimony to the State legislature. At a hearing in Albany on February 19, 1908, Knapp spoke on the question "Do Working Women Need the Ballot?" Her speech was later published by the New York State Association Opposed to the Extension of Suffrage to Women. By this point, Knapp's views were very different from Gilman's. Knapp argued that women worked only out of need, not because they wanted to. This went against Gilman's idea that work could help women reach their full potential. Knapp believed women had failed to cooperate with men. Gilman, however, celebrated women's ability to work together. Gilman's later writings became more critical, calling women who opposed suffrage "traitors."

Final Years

Adeline Knapp died in California on June 6, 1909, after a long illness. Her obituary in The New York Times on June 26, 1909, quoted a letter she wrote. In it, she said that her experience in Hawaii convinced her that "newspaper work does not offer a real career for a woman—the sacrifices are too great." Because of this, Knapp wrote, "I went away from cities altogether and lived for two or three years alone in a canyon in the Contra Costa foothills. I built a house there, a small one, all myself, cut down trees, tramped the woods, wrote a book or two, and did a lot of thinking."

See Also

Images for kids

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |