Ina Coolbrith facts for kids

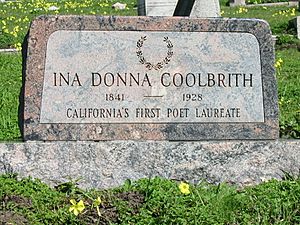

Ina Donna Coolbrith (born Josephine Donna Smith; March 10, 1841 – February 29, 1928) was an American poet, writer, and librarian. She was a very important person in the San Francisco Bay Area's writing community. People called her the "Sweet Singer of California." She was the first California Poet Laureate, which means she was the official poet for the state of California. She was also the first poet laureate of any American state.

Ina Coolbrith was the niece of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints founder Joseph Smith. As a child, she left the Mormon community. She spent her teenage years in Los Angeles, California, where she started publishing her poems. After a difficult early marriage, she moved to San Francisco. There, she met writers Bret Harte and Charles Warren Stoddard. They became known as the "Golden Gate Trinity" and worked closely with the literary magazine Overland Monthly. Important writers like Mark Twain, Ambrose Bierce, and Alfred Lord Tennyson praised her poetry. She often hosted literary gatherings, called salons, at her home in Russian Hill. At these events, she helped new writers connect with publishers. Coolbrith also became good friends with the poet Joaquin Miller and helped him become famous around the world.

While Miller traveled in Europe and visited Lord Byron's tomb, Coolbrith stayed behind. She took care of Miller's Wintu daughter and other members of her own family. Because of this, she moved to Oakland and became the city librarian. Her long work hours meant she had less time for her own poetry. However, she guided many young readers, including famous authors like Jack London and dancer Isadora Duncan. After working as a librarian for 19 years, she was let go. She then moved back to San Francisco. Members of the Bohemian Club invited her to be their librarian.

Coolbrith started writing a history of California literature, which included many stories about her own life. But the fire that followed the 1906 San Francisco earthquake destroyed all her work. Author Gertrude Atherton and her friends from the Bohemian Club helped her get a new house. She then started writing again and continued to host her literary salons. She traveled to New York City several times. With fewer worries, she wrote many more poems.

On June 30, 1915, Coolbrith was officially named California's poet laureate. She kept writing poetry for eight more years. Her poems covered many different topics, not just the sad or happy themes often expected from women. Her writing was known for being "singularly sympathetic" and "palpably spontaneous." She described nature in a very vivid way, which helped change Victorian poetry. Her style was like a bridge to newer poetry styles, like the Imagist school and the work of Robert Frost. California poet laureate Carol Muske-Dukes said that even though Coolbrith's poems had a "high tea lavender style" (meaning they were a bit formal, like British poetry), "California remained her inspiration."

Contents

Early Life and Family History

Ina Coolbrith was born Josephine Donna Smith in Nauvoo, Illinois. She was the youngest of three daughters of Agnes Moulton Coolbrith and Don Carlos Smith. Don Carlos was the brother of Joseph Smith, who founded Mormonism. Ina's father died of malarial fever four months after she was born. One of her sisters died a month after that. In 1842, Coolbrith's mother married Joseph Smith.

In June 1844, Joseph Smith was killed. Coolbrith's mother decided to leave the Mormon community. She moved to Saint Louis, Missouri, where she married a printer and lawyer named William Pickett. They had twin sons. In 1851, Pickett traveled with his new family to California in a wagon train. During the long journey, young Ina read books by Shakespeare and Byron. When she was ten, Ina rode ahead of the wagon train with the famous African-American scout Jim Beckwourth. They rode through what is now called Beckwourth Pass. The family settled in Los Angeles, California, and Pickett started his law practice.

To avoid being linked to her past family or Mormonism, Ina's mother started using her maiden name, Coolbrith, again. The family decided not to talk about their Mormon past. Most people only learned about Ina Coolbrith's background after she died. However, Coolbrith did stay in touch with her Smith relatives. She wrote letters to her first cousin Joseph F. Smith throughout her life and often showed her love and respect for him.

Coolbrith, sometimes called "Josephina" or "Ina," started writing poems at age 11. Her first poem, "My Ideal Home," was published in a newspaper in 1856 under the name Ina Donna Coolbrith. Her work also appeared in the Poetry Corner of the Los Angeles Star and in the California Home Journal. As she grew up, Coolbrith was known for her beauty. She was chosen to open a ball with Pío Pico, who was the last Mexican governor of California.

In April 1858, at 17, Coolbrith married Robert Bruce Carsley, an iron worker and actor. She ended this difficult early marriage on December 30, 1861. She also sadly lost her infant son. Her later poem, "The Mother's Grief," was a tribute to her lost son. But she never publicly explained its meaning. Her friends only found out she had been a mother after she died.

In 1862, Coolbrith moved to San Francisco with her mother, stepfather, and twin half-brothers. She wanted to feel better after a sad time. She also changed her name from Josephine Donna Carsley to Ina Coolbrith. In San Francisco, she found a job as an English teacher.

A Talented Poet

Coolbrith soon met Bret Harte and Samuel Langhorne Clemens, who wrote as Mark Twain, in San Francisco. She published poems in the Californian, a new literary newspaper started in 1864 and edited by Harte. In 1867, four of Coolbrith's poems appeared in The Galaxy. In July 1868, Coolbrith wrote a poem called "Longing" for the first issue of the Overland Monthly. She also helped Harte unofficially choose poems, articles, and stories for the magazine. She became friends with actress and poet Adah Menken. Coolbrith also worked as a schoolteacher to earn more money.

For ten years, Coolbrith wrote one poem for each new issue of the Overland Monthly. After four of her poems were published in a book edited by Harte in 1866, her poem "The Mother's Grief" received a good review in The New York Times. Another poem, "When the Grass Shall Cover Me," was included in a book of John Greenleaf Whittier's favorite poems by other writers, called Songs of Three Centuries (1875). Coolbrith's poem was considered the best in that collection. In 1867, Josephine Clifford, who had recently lost her husband, came to the Overland Monthly as a secretary. She and Coolbrith became lifelong friends.

Coolbrith's writing connected her with poet Alfred Lord Tennyson and naturalist John Muir. She also worked with Charles Warren Stoddard, who helped Harte edit the Overland Monthly. As editors and people who decided what was good literature, Harte, Stoddard, and Coolbrith were known as the "Golden Gate Trinity." Stoddard once said that Coolbrith never had any of her writings rejected by a publisher. Coolbrith met writer and critic Ambrose Bierce in 1869. Bierce thought Coolbrith's best poems were "California," which she wrote for the University of California in 1871, and "Beside the Dead," written in 1875.

In mid-1870, Coolbrith met the unique poet Cincinnatus Hiner Miller. Coolbrith introduced him to the San Francisco writing community. Miller described Coolbrith as "divinely tall, and most divinely fair." When Coolbrith learned that Miller admired the legendary outlaw Joaquin Murrieta, she suggested he use the name Joaquin Miller as his pen name. She also suggested he dress in a more recognizable mountain man style.

Coolbrith then helped Miller get ready for his trip to England. He planned to place a laurel wreath on the tomb of Lord Byron, a poet they both admired. They gathered California Bay Laurel branches in Sausalito and took portrait photos together. Coolbrith wrote "With a Wreath of Laurel" about this event. Miller traveled to New York by train, calling himself "Joaquin Miller" for the first time. He arrived in London by August 1870. When he placed the wreath at the Church of St. Mary Magdalene, Hucknall, it caused a stir among the English church leaders. After this, Miller was nicknamed "The Byron of the West."

Life as a Librarian

Coolbrith had hoped to travel to the East Coast and Europe with Miller. But she stayed in San Francisco because she felt she needed to care for her mother and her sick, widowed sister Agnes, who had two children. In late 1871, she took on another person to care for. Joaquin Miller brought her a teenage Native American girl (who many thought was his daughter) to look after while he traveled abroad again.

At a literary dinner on May 5, 1874, Coolbrith was made an honorary member of the Bohemian Club. This allowed the club members to help her with money quietly. But it wasn't enough. Coolbrith moved to Oakland to set up a larger home for her family. Coolbrith's sister Agnes died in late 1874, and her niece and nephew continued to live with Coolbrith. Coolbrith wrote "Beside the Dead" because she was sad about losing her sister. Her mother Agnes died in 1876.

To support her household, Coolbrith became the librarian for the Oakland Library Association in late 1874. This was a library where people paid a fee to borrow books. In 1878, the library became the Oakland Free Library, the second public library in California. Coolbrith earned $80 a month, which was less than a man would have received. She worked 6 days a week, 12 hours a day. Her own poetry suffered because of her long hours. She published only a few poems over the next 19 years. This was a difficult time for her as a poet.

At the library, she had a personal way of working. She talked with people about their interests and chose books she thought they would like. In 1886, she became friends with and guided 10-year-old Jack London in his reading. London called her his "literary mother." Twenty years later, London wrote to Coolbrith to thank her.

Coolbrith also guided young Isadora Duncan, who later said Coolbrith was "a very wonderful" woman with "very beautiful eyes that glowed with burning fire and passion." Duncan wrote in her autobiography that Coolbrith, as a librarian, was always happy with the young dancer's book choices.

In 1881, Coolbrith's poems were published in a book called A Perfect Day, and Other Poems. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow read it and said, "I know that California has at least one poet." He added, "I have been reading them with delight." Edward Rowland Sill, a professor at the University of California, wrote a letter introducing Coolbrith to publisher Henry Holt. He simply said, "Miss Ina Coolbrith, one of our few really literary persons in California, and the writer of many lovely poems; in fact, the most genuine singer the West has yet produced." Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier wrote to Coolbrith that her "little volume" of poetry was very popular and should be published on the East Coast. He told her "there is no verse on the Pacific Slope which has the fine quality of thine."

Starting in 1865 in San Francisco, Coolbrith held literary meetings at her home. People would read poetry and discuss topics, like the famous European salons. She helped writers like Gelett Burgess and Laura Redden Searing become more known.

In the 1880s, Ambrose Bierce, who had been a good friend, started writing critical things about Coolbrith's work. This ended their friendship.

Coolbrith published poems in The Century in 1883, 1885, 1886, and 1894. All four poems were included in her 1895 book, Songs from the Golden Gate. This was a new edition of her 1881 collection, with about 40 more poems. In New York, a reviewer praised her as "a true, melodious and natural singer." Her work was described as having "great delicacy and refinement of feeling."

In September 1892, Coolbrith was told she had three days to leave her job as librarian. Her nephew Henry Frank Peterson replaced her. Her literary friends were very upset and wrote about it in the San Francisco Examiner. However, Peterson's changes to the library were successful. He opened the library on Sundays and holidays and made it easier for people to access books.

In 1893, at a large meeting of women in Chicago, Coolbrith was called "the best known of California writers." Coolbrith was asked to write a poem for the event. In October 1893, she brought her poem "Isabella of Spain" to Chicago to help dedicate a sculpture. Important women like Susan B. Anthony were there to listen.

Coolbrith's friends were worried about her future. John Muir often sent Coolbrith letters and fruit. In late 1894, he suggested she become San Francisco's librarian. Coolbrith thanked him but said, "No, I cannot have Mr. Cheney's place. I am disqualified by sex." At that time, San Francisco required its librarian to be a man.

In 1894, Coolbrith honored poet Celia Thaxter with a poem called "The Singer of the Sea."

Her second poetry book, Songs from the Golden Gate, was published in 1895. It included "The Mariposa Lily," which described California's natural beauty. It also had "The Captive of the White City," which talked about the unfair treatment of Native Americans in the late 1800s. The book also contained "The Sea-Shell" and "Sailed," two poems where Coolbrith described a woman's love with deep feeling and vivid images. This style was similar to the later Imagist school of Ezra Pound and Robert Frost. The book included four black and white pictures by William Keith that showed the poems visually. The book was well-received in London.

Because of her friends, Coolbrith got a librarian job at San Francisco's Mercantile Library Association in 1898. She moved back to Russian Hill in San Francisco. In January 1899, artist William Keith and poet Charles Keeler helped her get a part-time job as librarian of the Bohemian Club. Her first task was to edit a book of poems by Daniel O'Connell, a co-founder of the Bohemian Club, after he died. Her salary was $50 a month, less than she made in Oakland. But her duties were light, so she had more time to write. She also started working on a history of California literature.

Earthquake and Fire

By February 1906, Coolbrith was not feeling well. She was often sick in bed. Still, in March 1906, she gave a long reading to the Pacific Coast Woman's Press Association about "Some Women Poets of America."

A month later, a big disaster happened. The terrible fire that followed the great San Francisco earthquake in April 1906 burned Coolbrith's home to the ground. Right after the earthquake, but before the fire reached her house, Coolbrith left carrying a pet cat. She thought she would return soon. Her student boarder and her friend Josephine Zeller could only carry another cat and a few small bundles of letters and Coolbrith's scrapbook. Joaquin Miller saw heavy smoke from across the bay and took the ferry to San Francisco to help Coolbrith save her valuable things. But soldiers stopped him because they had orders to prevent looting. In the fire, Coolbrith lost 3,000 books, including very valuable signed first editions. She also lost artwork by Keith, many personal letters from famous people like Whittier and Clemens, and, worst of all, her almost finished book that was part autobiography and part history of California's early writers.

Coolbrith lived in temporary places for a few years while friends raised money to build her a new house. From New York, her old friend Mark Twain sent three signed photos of himself that sold for $10 each. In February 1907, the San Jose Women's Club held an "Ina Coolbrith Day" to help get a state pension for Coolbrith and support a book project. In June 1907, the Spinners' Club printed a book called The Spinners' book of fiction. The money from this book was given to Coolbrith. Frank Norris, Mary Hallock Foote, and Mary Hunter Austin were among the authors who wrote stories for it. The main person behind this effort was Gertrude Atherton, a writer who saw Coolbrith as a link to California's literary beginnings. When the book didn't raise enough money, Atherton added enough from her own pocket to start building.

A new house was built for Coolbrith at 1067 Broadway on Russian Hill. Once settled there, she started hosting her salons again. In 1910, she received a trust fund from Atherton. From 1910 to 1914, with money from Atherton and her Bohemian friends, Coolbrith spent time between New York City and San Francisco, writing poetry. In four winters, she wrote more poetry than she had in the previous 25 years.

California's Poet Laureate

In 1911, Coolbrith became the president of the Pacific Coast Woman's Press Association. A park was also dedicated to her at 1715 Taylor Street, one block from her old home. Coolbrith became an honorary member of the California Writers Club around 1913. In 1913, Ella Sterling Mighels started the California Literature Society, which met informally once a month at Coolbrith's Russian Hill home. Mighels, who is called California's literary historian, said she learned a lot from Coolbrith and these meetings.

For the 1915 Panama–Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, Coolbrith was named President of the Congress of Authors and Journalists. In this role, she sent over 4,000 letters to famous writers and journalists around the world. At the Exposition on June 30, Senator James D. Phelan praised Coolbrith. He said her early friend Bret Harte called her the "sweetest note in California literature." Phelan added, "she has written little, but that little is great. It is of the purest quality, finished and perfect, as well as full of feeling and thought." The Overland Monthly reported that "eyes were wet throughout the large audience" when Coolbrith was crowned with a laurel wreath by Benjamin Ide Wheeler, President of the University of California. He called her the "loved, laurel-crowned poet of California." After many speeches in her honor, Coolbrith, wearing a black robe with a sash of bright orange California poppies, spoke to the crowd. She said, "There is one woman here with whom I want to share these honors: Josephine Clifford McCracken. For we are linked together, the last two living members of Bret Harte's staff of Overland writers." McCracken then joined Coolbrith on stage. Her official title as California Poet Laureate was confirmed in 1919.

Several months after the San Francisco fair, at the Panama–California Exposition in San Diego, there were Authors' Days featuring 13 California writers. November 2, 1915, was "Ina Coolbrith Day." Her poems were read, a talk about her life was given, and her poetry was set to music and performed.

In 1916, Coolbrith sent copies of her poetry books to her cousin Joseph F. Smith. He then shared that she was a niece of Joseph Smith, which upset her. She told him, "To be crucified for a faith in which you believe is to be blessed. To be crucified for one in which you do not believe is to be crucified indeed." She said she wasn't angry, but she wasn't pleased.

Coolbrith continued to write and work to support herself. From 1909 to 1917, she carefully collected and edited a book of Stoddard's poetry. She wrote a foreword and added her short memorial poem "At Anchor." At 80, McCracken wrote to Coolbrith to complain that she still had to work for a living. She said, "The world has not used us well, Ina; California has been ungrateful to us."

Later Life and Lasting Impact

In May 1923, Coolbrith's friend Edwin Markham found her in New York, "very old, ill and moneyless." He asked Lotta Crabtree to help her. Coolbrith, who had arthritis, was brought back to California. She settled in Berkeley and was cared for by her niece. In 1924, Mills College gave her an honorary Master of Arts degree. Coolbrith published Retrospect: In Los Angeles in 1925. In April 1926, she had visitors like her old friend, art supporter Albert M. Bender, who brought young Ansel Adams to meet her. Adams took a photo of Coolbrith sitting near one of her white Persian cats, wearing a large white mantilla on her head.

Coolbrith died on Leap Day, February 29, 1928. She was buried in Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland. Her grave (located at 37°50′00″N 122°14′20″W / 37.8332°N 122.2390°W) was unmarked until 1986. Then, a literary group called The Ina Coolbrith Circle placed a headstone. A mountain peak near Beckwourth Pass in the Sierra Nevada mountains is named Mount Ina Coolbrith. It is about 7,900-foot (2,400 m) tall. Near her Russian Hill home, Ina Coolbrith Park, which is a series of terraces on a steep hill, received a memorial plaque in 1947. The park is known for its "meditative setting and spectacular bay views."

Wings of Sunset, a book of Coolbrith's later poetry, was published the year after she died.

In 1933, the University of California started the Ina Coolbrith Memorial Poetry Prize. This award is given every year to college students who write the best unpublished poems.

The California Writers Club (CWC) sometimes gives the Ina Coolbrith Award to a member who has provided "exemplary service." In 2009, Joyce Krieg received the award. In 2011, Kelly Harrison received the award. In his 1997 novel Separations, author Oakley Hall made Coolbrith and her literary friends from the 1870s main characters in the story. Hall supported Coolbrith's legacy and helped new California writers through the Squaw Valley Writer's Conference.

In 2001, a sculpture by Scott Donahue was placed in Oakland's central Frank Ogawa Plaza. The artist said his 13-foot-2-inch (4.01 m) colorful statue was a mix of 20 important women from Oakland's history and present, including Coolbrith, Isadora Duncan, and Julia Morgan. The sculpture was later moved to Union Point Park in 2005.

In 2003, the City of Berkeley installed 120 cast-iron plates with poems on them along a downtown street. This became the Addison Street Poetry Walk. Former U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Hass decided that one of Coolbrith's poems should be included. A 55-pound (25 kg) plate with Coolbrith's poem "Copa De Oro (The California Poppy)" is set into the sidewalk at a busy corner.

In 2016, a path in the Berkeley Hills was renamed for Coolbrith. When paths in the Berkeley hills were named after Bret Harte, Charles Warren Stoddard, Mark Twain, and other writers in Coolbrith's group, women were not included. Thanks to the efforts of the City of Berkeley and other groups, a stairway in the hills was changed from Bret Harte Lane to Ina Coolbrith Path. (Bret Harte still has three paths named for him in the area.) At the bottom of the stairway, the Berkeley Historical Society has placed a plaque to remember Coolbrith.

See also

- List of descendants of Joseph Smith Sr. and Lucy Mack Smith

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |