Alchemy in the medieval Islamic world facts for kids

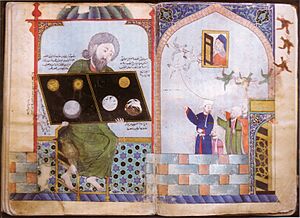

Alchemy in the medieval Islamic world was a mix of old traditions and early practical chemistry. It was studied by Muslim scholars during the Islamic Golden Age. The word "alchemy" comes from the Arabic word kīmiyāʾ. This word might have come from the ancient Egyptian word kemi, which means "black".

After the Western Roman Empire fell, and the Islamic world grew, the study of alchemy moved to the Caliphate. This was a time when Islamic civilization made many important discoveries.

Contents

What Islamic Alchemists Added to Alchemy

Islamic scholars first translated old texts about alchemy. These texts came from Hermeticism and Gnosticism. Over time, they started to think for themselves and do their own experiments.

They connected alchemy with their Islamic faith. They believed that the goal of alchemy was to find a "God-image" inside oneself. They saw things like stone, water, and other materials as parts of this inner journey. Through this journey, alchemists could connect with God.

Islamic alchemists also used more poetic language in their writings. They often wrote about the joining of male and female, or the sun and moon. They saw alchemy as a way to change the alchemist's own mind and spirit. They believed that the "fire" that helped this change was the love of God.

Important Alchemists and Their Books

Many scholars in the Islamic world studied alchemy. Here are some of the most famous ones.

Khālid ibn Yazīd

Ibn al-Nadīm, a well-known writer, said that Khālid ibn Yazīd was the first Muslim alchemist. He is thought to have learned alchemy from a Christian teacher named Marianos. It's not fully clear if this story is true.

Khālid ibn Yazīd is believed to have written several books on alchemy. These include The Book of Pearls and The Paradise of Wisdom. However, some people think these books might have been written by others using his name.

Jābir ibn Ḥayyān

Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (who died around 806–816) is often called the "father of chemistry." He wrote many books in Arabic. His works have the oldest known way to group chemical substances. They also show the oldest instructions for making inorganic compounds, like sal ammoniac, from organic things such as plants or hair.

Some of Jābir's books were translated into Latin. In Europe, an unknown writer started writing alchemical books under the name "pseudo-Geber" in the 13th century.

Abū Bakr al-Rāzī

Abū Bakr ibn Zakariyā’ al-Rāzī (also known as Rhazes) was born around 865. He was a famous Persian doctor. He also wrote several books about alchemy. One of his most famous works is Secret of Secrets.

Ibn Umayl

Muḥammad ibn Umayl al-Tamīmī was an Egyptian alchemist from the 10th century. He focused on the symbolic and mystical side of alchemy. One of his books is The Book on Silvery Water and Starry Earth. This book explains his poem, The Epistle of the Sun to the Crescent Moon. It also includes many quotes from older writers.

Ibn Umayl's work was very important for alchemy in Europe. His book "Silvery Water" was even reprinted in a collection of alchemy texts.

Al-Tughrai

Al-Tughrai was a Persian doctor who lived in the 11th and 12th centuries. His book, The Lanterns of Wisdom and the Keys of Mercy, is one of the first books about material sciences.

Al-Jildaki

Al-Jildaki was an Egyptian alchemist. In his book, he stressed how important it was to do experiments in chemistry. He described many experiments in his work.

Ideas About Alchemy and Chemistry

| Hot | Cold | |

| Dry | Fire | Earth |

| Moist | Air | Water |

Jābir looked at each of Aristotle's four basic elements: fire, earth, air, and water. He described them using four qualities: hotness, coldness, dryness, and moistness. For example, fire is hot and dry.

Jābir believed that metals were made in the Earth. They formed from a mix of sulfur (which gave hot and dry qualities) and mercury (which gave cold and moist qualities). These were not the everyday sulfur and mercury we know. Instead, they were ideal, perfect forms of these substances. The type of metal that formed depended on how pure the mercury and sulfur were. It also depended on how much of each was present.

Later, alchemist al-Rāzī (around 865–925) agreed with Jābir's mercury-sulfur idea. But he added a third part: salt.

Jābir thought that if you could change the qualities of one metal, you could turn it into a different metal. This idea led to the search for the philosopher's stone in Western alchemy. The philosopher's stone was a legendary substance that could turn ordinary metals into gold.

Alchemy Tools and Methods

Al-Rāzī wrote about many chemical processes. These included distillation (separating liquids by heating and cooling), calcination (heating a substance to a high temperature), and solution (dissolving a substance). Other methods were evaporation, crystallization, sublimation (turning a solid directly into a gas), and filtration. Some of these methods were also used by alchemists before Islam.

In his book Secret of Secrets, Al-Rāzī listed many tools.

- Tools for melting substances: These included a hearth (a furnace), bellows (to blow air into the fire), a crucible (a pot for melting), and a ladle. They also used tongs, scissors, a hammer, and a file.

- Tools for preparing substances: These included a cucurbit and still (for distillation), and a receiving flask. They also used aludels (special glass vessels), goblets, and flasks. Other tools were a cauldron, earthenware pots, and a water bath or sand bath. They also had ovens, funnels, sieves, and filters.

See also

In Spanish: Alquimia en el mundo islámico medieval para niños

In Spanish: Alquimia en el mundo islámico medieval para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |