Aleijadinho facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Aleijadinho

|

|

|---|---|

Supposed posthumous portrait by Euclásio Ventura, 19th century, no contemporary depiction is known

|

|

| Born | 29 August 1738 Vila Rica (present day Ouro Preto), Minas Gerais, State of Brazil

|

| Died | 18 November 1814 (aged 76) Vila Rica, Minas Gerais, State of Brazil

|

| Known for | Sculpting, architecture |

| Movement | Portuguese colonial Baroque |

| Signature | |

Antônio Francisco Lisboa (born around 1730 or 1738 – died November 18, 1814), better known as Aleijadinho (which means "little cripple" in Portuguese), was a famous sculptor, carver, and architect in Colonial Brazil. He is known for his amazing artworks found in many churches across Brazil. His style mixed Baroque and Rococo art. Many experts agree that Aleijadinho was the greatest artist of colonial Brazil. Some even say he was the most important Baroque artist in all of the Americas.

We don't know much for sure about his life. Most of what we know comes from a biography written about 40 years after he died. This makes it hard to know exactly what is true and what is just a story. We mostly learn about him through the art he left behind. However, even with his art, it's sometimes hard to be sure if a piece was made by him or by his students. This is because many of the over 400 artworks linked to his name don't have clear documents proving he made them. They are often linked to him because they look like his known works.

All of Aleijadinho's art, including carvings, building designs, and statues, was made in the state of Minas Gerais. You can find his works in cities like Ouro Preto, Sabará, São João del-Rei, and Congonhas. Two of the most important places with his art are the Church of Saint Francis of Assisi in Ouro Preto and the Sanctuary of Bom Jesus of Matosinhos.

Contents

Biography

Most of what we know about Antônio Francisco Lisboa comes from a book written in 1858 by Rodrigo José Ferreira Bretas. This book was written 44 years after Aleijadinho passed away. Bretas said he used old documents and talked to people who knew the artist. However, some modern experts think parts of this book might be made up or exaggerated. They believe it was written to make Aleijadinho seem like a bigger hero and artist for Brazil. Even so, Bretas's book is the oldest and most detailed story of Aleijadinho's life. Later biographies often used his information. It's just hard to tell what is real and what is a legend.

The first official mention of Aleijadinho was in 1790. A captain named Joaquim José da Silva wrote about the artist's important works and some details about his life. This was done while Aleijadinho was still alive. Bretas later used parts of this old document for his book.

Early years

Antônio Francisco Lisboa was the son of a respected Portuguese builder and architect, Manuel Francisco Lisboa. His mother was Isabel, an African slave. Records show that Antônio was born a slave and was baptized on August 29, 1730, in Vila Rica (now Ouro Preto). His father freed him at his baptism. However, many believe he was born in 1738. His death certificate says he was 76 when he died in 1814, which would mean he was born in 1738. The Aleijadinho Museum in Ouro Preto accepts the 1738 date. In 1738, Aleijadinho's father married Maria Antônia de São Pedro. Antônio grew up with his four half-siblings from this marriage.

According to Bretas, Aleijadinho learned drawing, architecture, and sculpture from his father. He might also have learned from a draftsman and painter named João Gomes Batista. From 1750 to 1759, he might have studied at a seminary in Ouro Preto. There, he would have learned grammar, Latin, math, and religion. During this time, he helped his father with projects like the Church of Antônio Dias. He also worked with his uncle, Antônio Francisco Pombal, who was a carver. His first known individual project was in 1752. It was a design for a fountain in the courtyard of the Governors Palace in Ouro Preto.

Maturity

Around 1756, Aleijadinho might have visited Rio de Janeiro. This trip could have influenced his art. Two years later, he made a soapstone fountain for a hospice. Soon after, he started working as an independent artist. Because he was a mulatto (of mixed African and European descent), he often had to accept jobs as a day laborer, not as a master. From the 1760s until near his death, Aleijadinho created many artworks. However, without clear documents, many of these works are only "attributed" to him based on their style.

After his father died in 1767, Aleijadinho, as a son born outside of marriage, did not receive anything in the will. The next year, he joined a military regiment in Ouro Preto for three years. He continued his art during this time. He received important jobs, like designing the front of the Church of Our Lady of Carmel in Sabará. He also created the pulpits for the Church of Saint Francis of Assisi in Ouro Preto.

Around 1770, he set up his own workshop. This workshop grew quickly and was officially recognized in 1772. On August 5, 1772, he became a member of the Brotherhood of São José in Ouro Preto. In 1776, the governor of Minas Gerais called on skilled workers, including Aleijadinho, to help rebuild a fort. Aleijadinho might have traveled to Rio de Janeiro for this, but he was later excused. In Rio, he officially recognized a son he had with Narcisa Rodrigues da Conceição. His son, also named Manuel Francisco Lisboa, later became an artisan.

According to Bretas, Aleijadinho was healthy and enjoyed parties until around 1777. After that, he started showing signs of a serious illness. Over the years, this illness deformed his body and made it hard for him to work. It caused him a lot of pain. Even today, doctors and historians don't know exactly what his illness was. Despite his increasing difficulties, Aleijadinho kept working hard. In 1787, he became a judge for the Brotherhood of Saint Joseph.

Final years and death

In 1796, Aleijadinho received another very important job. He was asked to create sculptures for the Via Sacra (Stations of the Cross) and the Prophets for the Sanctuary of Bom Jesus of Matosinhos in Congonhas. These are considered his greatest works. In 1804, a census showed his son, daughter-in-law, and a grandson living with him. Between 1807 and 1809, his illness was very advanced. He closed his workshop but still did some work. From 1812 onwards, his health got much worse. He relied heavily on those who cared for him.

Aleijadinho moved to a house near the Church of Our Lady of Carmel in Ouro Preto. This was so he could oversee works being done by his student, Justino de Almeida. By this time, he was almost blind and could barely move. He later moved back to his old home for a short time. Then, he settled at his daughter-in-law's house. She cared for him until he died on November 18, 1814. Aleijadinho was buried in the Mother Church of Antônio Dias.

The man and his illness

We don't know much about Aleijadinho's personal life. We know he liked to dance and eat well. He also fell in love with Narcisa, with whom he had a son. There's no record of his thoughts on art, society, or politics. He always worked on commission, earning a daily wage. He didn't become rich and was said to be careless with money. He was robbed several times. However, he also gave money to the poor. He had three slaves: Maurício, his main helper; Agostinho, a carving assistant; and Januário, who guided the donkey he used to travel.

Bretas wrote that after 1777, Aleijadinho began to show signs of a mysterious disease. This disease led to his nickname, Aleijadinho, meaning 'little cripple'. His body slowly became deformed, causing him constant pain. It's said he lost several fingers, leaving only his index and thumb. He also lost all his toes, forcing him to walk on his knees. To work, he had to have his tools tied to his hands. When his illness was very bad, he had to be carried everywhere. Receipts for payments to slaves who carried him still exist. His face was also damaged. Because of his appearance, Aleijadinho was said to be often angry and suspicious. He thought even praise for his art was a hidden joke.

To hide his deformities, he wore loose clothes and big hats. He also started working mostly at night or inside a closed space with curtains. This was so people couldn't see him easily. According to Bretas, Aleijadinho's daughter-in-law said that in his last two years, he was often in bed. One side of his body was covered in sores. He often prayed for death to end his suffering. However, other accounts from his time don't fully agree on how bad his deformities were. Some said he had lost his hands, while others said his hands were just paralyzed. An examination of his remains in 1930 was not conclusive.

Many possible diseases have been suggested to explain his condition. These include leprosy (though unlikely, as he wasn't excluded from society), deforming rheumatism, yaws, scurvy, injuries from a fall, rheumatoid arthritis, poliomyelitis, and porphyria. Porphyria causes sensitivity to light, which could explain why he preferred to work at night.

The idea of Aleijadinho as a great, unique artist started with Bretas's biography. In the early 1900s, artists and writers in Brazil saw Aleijadinho as a symbol of Brazilian culture. He was a mulatto who mixed Portuguese traditions with something new and original. This helped create the "Aleijadinho myth," making him an important figure in national culture.

His illness also became a big part of this story. Some researchers point out that receipts signed by Aleijadinho in 1796 show his handwriting was still clear. This makes it hard to believe he had lost his fingers by then, as some stories claim. However, his handwriting did get worse after that date. Today, Aleijadinho's story, including his illness, is often used to attract tourists to Ouro Preto. Many experts have tried to separate the facts from the legends about his life.

Iconography

There are no known portraits of Aleijadinho made while he was alive. However, in the early 1900s, a small painting of a well-dressed mulatto with hidden hands was found. It was sold as a portrait of Aleijadinho. In 1972, the Legislative Assembly of Minas Gerais officially recognized this painting as the only true image of Antônio Francisco Lisboa. This is the image you see at the beginning of this article. Some Brazilian artists have also created their own imagined portraits of him.

Historical and artistic context

Baroque and Rococo

Aleijadinho worked during a time when art styles were changing from Baroque to Rococo. His art shows features of both. The Baroque style, which started in Europe in the 1600s, was grand and dramatic. It used lots of decoration, strong emotions, and rich materials. It was often used by the Catholic Church and powerful rulers to show their glory. Baroque art tried to combine architecture, painting, sculpture, and music into one big, impressive experience.

In Brazil, Baroque art was mostly about religion. Missionaries and the Church played a huge role in colonial life. They built many churches and controlled much of the art. Brazilian Baroque art used rich decorations and forms to teach religious stories. It aimed to make people feel strong emotions and connect with their faith. This was important because most people couldn't read.

Rococo is like a softer, lighter version of Baroque. It uses more open, flowing, and bright decorations. Rococo architecture has more elegant fronts, bigger windows, and interiors that are mostly white. It uses delicate carvings, often shaped like shells, with lighter colors. Even though Rococo was lighter, the religious art in Brazil still kept the dramatic and emotional feel of the Baroque.

The gold cycle

Minas Gerais was a newer settlement area in Brazil. This meant artists there had more freedom to build new churches in the latest styles, like Rococo. The many Rococo churches in Minas Gerais are important because they show a special time in Brazilian history. This was when the region became rich from gold and diamond discoveries. It was also the first place in Brazil to have many cities.

The unique art style in Minas Gerais also came from its isolation and sudden wealth. The style was strongest in Vila Rica (now Ouro Preto), founded in 1711. It also thrived in other mining towns. When the gold started to run out around 1760, the region's cultural peak also began to fade. But this was when its unique style, moving towards Rococo, reached its best with the mature works of Aleijadinho.

The wealth of the 1700s also led to a rich urban class interested in art. Religious brotherhoods played a big role in Minas Gerais society. Aleijadinho was part of the Brotherhood of São José, which included many carpenters. These brotherhoods sponsored art, helped their members, and cared for the poor. Many became very wealthy and competed to build luxurious churches. They were also important in building a sense of community among people who were not part of the Portuguese elite.

At the time Aleijadinho worked, Minas Gerais was politically and socially restless. The Portuguese Crown demanded gold from the mines, causing great tension. This led to the Minas Gerais Conspiracy, a movement for independence. Aleijadinho knew one of the conspirators, but his political views are unknown.

Rococo is a softer, lighter version of Baroque. In Minas Gerais, it's thought that Rococo ideas spread through German and French engravings and Portuguese tiles. These were popular in Europe. Brazilian artists often learned by studying copies of famous European artworks. Portuguese artists also traveled to the region, bringing their knowledge of European art.

Rococo churches moved away from the heavy, gold-covered decorations of older Baroque churches. Instead, they used lighter, more open, and flowing designs. The architecture became more elegant, with larger windows for more light. Interiors often had a lot of white, with delicate carvings. The religious themes, however, remained dramatic, similar to the Baroque style.

Some experts see Aleijadinho as a bridge between Baroque and Rococo. Others call him a typical Rococo master. Still others see him as a perfect example of Baroque. His work also shows influences from popular art. This mix of high art and popular styles makes his work unique and important in Brazilian art.

Works

Authorship and personal style

It's hard to know for sure which artworks Aleijadinho made. Artists back then often didn't sign their work, and there aren't many old documents. Contracts and receipts between religious groups and artists are the most reliable sources. Comparing the style of known works to others can also help, but this is just a guess. Aleijadinho's unique style also inspired many other sculptors in Minas Gerais, who copied his work.

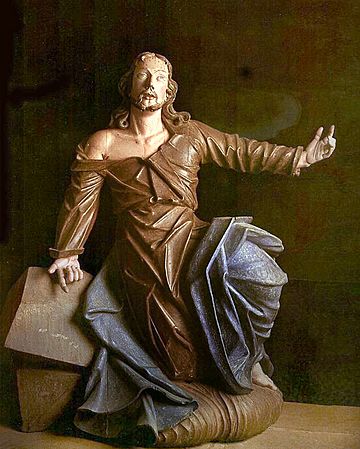

His style has some special features:

- Feet placed almost at a right angle.

- Drapery (folds in clothing) with sharp folds.

- Hands with square shapes and long thumbs. The index and pinky fingers are separate, while the ring and middle fingers are joined.

- A cleft chin.

- Half-open mouth with slightly full but well-shaped lips.

- Sharp, prominent nose with deep nostrils.

- Slanted, almond-shaped eyes with clear tear ducts. Eyebrows raised and joined in a "V" shape at the nose.

- Mustache starting from the nostrils, receding from the lips, and blending with the beard. The beard is set back on the face and split into two rolls.

- Short, somewhat stiff arms, especially in reliefs.

- Hair styled in wavy, grooved rolls, ending in spirals, with two locks over the forehead.

- Strong expressions and a piercing gaze.

For example, the image on the right, Nossa Senhora das Dores (Our Lady of Sorrows), is believed to be by him because of its style. It is now in the Museum of Sacred Art of São Paulo.

One expert, Beatriz Coelho, divides his style into three periods:

- 1760-1774: His style was still developing.

- 1774-1790: His style became more personal, firm, and idealized.

- 1790-death: His style became very extreme, moving away from natural looks to show spirituality and suffering.

It's also important to remember that artists often worked in workshops with many assistants. It's not always clear how much Aleijadinho himself worked on each piece. Master builders often changed original designs, and teams of craftsmen helped carve altars and sculptures. They followed the master's ideas but also left their own mark.

Because Aleijadinho is so famous, his works are very valuable. This creates pressure to "authenticate" (prove they are real) works, even without documents. Many works have been linked to him without clear proof, just based on style. Some experts have questioned these claims, saying it would have been impossible for him to create so many works, especially with his illness. They also suggest that collectors and art dealers might be trying to make anonymous works more valuable.

Main works

Gilded woodcarving

- Further information: Gilded woodcarving in Portugal

Aleijadinho helped design and create at least four large altarpieces (decorated structures behind altars). In these, his style was different from the usual Baroque-Rococo designs. A key feature was how he changed the top arch, replacing it with impressive statues. This shows he was mainly a sculptor. The first set was for the apse (curved part) of the Church of São José in Ouro Preto, made in 1772.

His most important altarpiece is in the Church of Saint Francis of Assisi in Ouro Preto. Here, the top part is filled with many figures, including a large group showing the Holy Trinity. This group blends with the ceiling, making the wall and ceiling seem to push upwards. All the wood carvings in this altarpiece have a sculptural feel, not just decorative. They create an interesting play of diagonal lines, which is a unique part of his style. He used this same idea in another large design for the Franciscan Church of São João del-Rei.

His last altarpieces were for the Church of Our Lady of Carmel in Ouro Preto, made between 1807 and 1809. By then, his illness meant he mostly supervised, rather than carved. These later works are simpler, with fewer decorations. They fit well with the Rococo style, using shell shapes and branches as main decorations.

Architecture

Aleijadinho also worked as an architect, but how much he did is debated. We only have documents for his designs of two church fronts: Our Lady of Carmel in Ouro Preto and Saint Francis of Assisi in São João del-Rei. Both started in 1776, but their designs were changed later.

It's often said that Aleijadinho designed the Church of Saint Francis of Assisi in Ouro Preto. However, documents only show he decorated it, creating altarpieces, pulpits, a doorway, and a washbasin. He also designed altarpieces and chapels, which are more like a decorator's job, even if they have architectural elements. Some experts say his documented facade designs look very different from the Ouro Preto church, suggesting he might not have designed the whole building. The Ouro Preto church looks more like older Baroque styles. The other two churches have decorated windows and are in the Rococo style.

The design of the Church of Saint Francis of Assisi in São João del-Rei, which was found, is also different from the church we see today. It was changed a lot by another artist, Francisco de Lima Cerqueira. So, Cerqueira is often called a co-author of that work.

Sculpture

Aleijadinho's greatest sculptures are at the Sanctuary of Bom Jesus de Matosinhos in Congonhas. These include 66 statues for the Via Sacra (Stations of the Cross) and the Twelve Prophets in the churchyard. The Via Sacra scenes, carved between 1796 and 1799, are very dramatic. The life-size statues are brightly colored, painted by Master Ataíde and possibly Francisco Xavier Carneiro.

The Via Sacra tradition comes from Italy. It shows scenes from the Passion of Jesus, from the Last Supper to his crucifixion. These scenes are meant to make people feel pity and sadness. They are usually placed in chapels leading up to a church on a hill, just like at the Sanctuary of Congonhas. This sanctuary was built by Feliciano Mendes to fulfill a promise, copying a similar shrine in Portugal.

Some experts say the intensity of the Brazilian Via Sacra is even greater than the Italian ones. Others see a strong, emotional style in them. Some also believe that the grotesque (ugly or distorted) Roman soldiers who torment Christ in the sculptures show a hidden protest against the Portuguese rule and the oppression of black people. They also see influences from popular folk art in his unique style.

By looking at the quality of the figures, experts think Aleijadinho didn't make all the Via Sacra statues himself. He likely made the figures in the first two chapels (the Holy Supper and the Agony in the Mount of Olives). For the other chapels, he probably carved only some main figures, like Christ and perhaps Saint Peter, and one of the Roman soldiers. His assistants would have carved the rest.

The other part of the Matosinhos set is the twelve sculptures of the prophets, made between 1800 and 1805. These statues have unusual proportions. Some think this is because of his assistants' skill or his illness. Others believe it was done on purpose to make the statues look better when seen from below. The drama of the set seems stronger because of these unique forms. The prophets have varied and theatrical poses, full of symbolic meanings related to their messages. Most of them look like young men with slender faces and trimmed beards. Only Isaiah and Nahum appear as old men with long beards. All wear similar tunics, except Amos, the shepherd-prophet, who wears a cloak like a peasant's. Daniel, with a lion at his feet, is especially well-made. Many believe it might be one of the only pieces in the set entirely carved by Aleijadinho.

The prophets have drawn a lot of attention. Some theories suggest they show a protest against the rulers, linking them to the Minas Gerais Conspiracy. Some even try to match each prophet to one of the conspirators. Others believe there might be hidden Masonic symbols. These theories are not widely accepted by experts, but they are popular in folk culture.

The overall design of the prophets is typical of international religious Baroque art: dramatic, theatrical, and expressive. One poet said that "Aleijadinho's prophets are not baroque, they are biblical," meaning they have a deep spiritual intensity. The entire Sanctuary of Congonhas, including the church, courtyard, and prophets, is now a World Heritage Site recognized by UNESCO.

Reliefs

Aleijadinho also created large reliefs (sculptures that stick out from a flat surface) for church doorways. He introduced a new style that became very popular in Brazil. A common feature was a crowned shield or emblem with angels on either side. This first appeared on the door of the Church of Carmel in Sabará. This style was similar to Portuguese Baroque designs.

Aleijadinho used this style for the doorways of the Franciscan churches in Ouro Preto and São João del-Rei. In Ouro Preto, the design became much more complex. Angels hold two shields, joined by Christ's crown of thorns and symbols of the Franciscan Order. Above this is a large medallion with the Virgin Mary, topped by a royal crown. The whole design is decorated with flowers, cherub heads, and ribbons. The Ouro Preto example also has an extra relief showing Saint Francis of Assisi receiving the stigmata. This is considered one of his most beautiful creations, combining sweetness and realism.

He also carved monumental washbasins and pulpits in soapstone for churches in Ouro Preto and Sabará. These all feature sculptural relief work, both decorative and showing descriptive scenes.

List of documented works

This information comes from an article by Felicidade Patrocínio.

- 1752 — Ouro Preto: Fountain of the Palace of the Governors. Designed by his father, carved by Aleijadinho.

- 1757 — Ouro Preto: Alto da Cruz Fountain. Designed by his father, carved by Aleijadinho.

- 1761 — Ouro Preto: Bust in the Fountain of Alto da Cruz.

- 1761 — Ouro Preto: Table and 4 benches for the Palace of the Governors.

- 1764 — Barão de Cocais: Carved the image of São João Batista in soapstone and designed the crossing arch inside the Sanctuary of São João Batista.

- 1770 — Sabará: Unspecified work for the Church of Our Lady of Carmel.

- 1771 — Rio Pomba: Measured the design for the main altar of the Mother Church.

- 1771–2 — Ouro Preto: Designed the main altar of the Church of São José.

- 1771 — Ouro Preto: Measured the design for the Church of Our Lady of Carmel.

- 1771 — Ouro Preto: Designed a butcher shop.

- 1771–2 — Ouro Preto: Pulpits for the Church of Saint Francis.

- 1773–4 — Ouro Preto: Cap of the chancel (area around the altar) of the Church of Saint Francis.

- 1774 — São João del-Rei: Approved the design of the Church of Saint Francis.

- 1774 — Sabará: Unspecified work for the Church of Our Lady of Carmel.

- 1774 — Ouro Preto: New design of the doorway of the Church of Saint Francis.

- 1775 — Ouro Preto: Designed the chancel and altar of the Church of Our Lady of Sorrows.

- 1777–8 — Ouro Preto: Inspected works at the Church of Our Lady of Sorrows.

- 1778 — Sabará: Inspected works at the Church of Our Lady of Carmel.

- 1778–9 — Ouro Preto: Designed the main altar of the Church of Saint Francis.

- 1779 — Sabará: Designed the railing and a statue for the Church of Our Lady of Carmel.

- 1781 — Sabará: Unspecified work for the Church of Our Lady of Carmel.

- 1781 — São João del-Rei: Commissioned to design the main altar of the Church of Saint Francis.

- 1781–2 — Sabará: Railing, pulpits, choir, and main doors of the Church of Our Lady of Carmel.

- 1785 — Morro Grande: Inspected works in the mother church.

- 1789 — Ouro Preto: Ara stones for the Church of Saint Francis.

- 1790 — Mariana: Registered as the second councilor in the Town Hall.

- 1790–4 — Ouro Preto: Main altar of the Church of Saint Francis.

- 1794 — Ouro Preto: Inspected works in the Church of Saint Francis.

- 1796–9 — Congonhas: Figures of the Passos da Paixão (Stations of the Cross) for the Sanctuary of Bom Jesus de Matosinhos.

- 1799 — Ouro Preto: Four angels on a litter for the Church of Our Lady of Pilar.

- 1800–5 — Congonhas: Twelve Prophets for the churchyard of the Sanctuary of Bom Jesus de Matosinhos.

- 1801–6 — Congonhas: Lamps for the Sanctuary of Bom Jesus de Matosinhos.

- 1804 — Congonhas: Organ box of the Sanctuary of Bom Jesus de Matosinhos.

- 1806 — Sabará: Designed the main altar (not accepted) for the Church of Our Lady of Carmel.

- 1807 — Ouro Preto: Altarpieces of Saint John and Our Lady of Sorrows for the Church of Our Lady of Carmel.

- 1808 — Congonhas: Candlesticks for the Sanctuary of Bom Jesus de Matosinhos.

- 1808–9 — Ouro Preto: Altarpieces of Saint Quiteria and Saint Lucy for the Church of Our Lady of Carmel.

- 1810 — São João del-Rei: Designed the frontispiece and railing for the mother church.

- 1829 — Ouro Preto: Lateral altarpieces for the Church of Saint Francis, completed after his death.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Aleijadinho para niños

In Spanish: Aleijadinho para niños