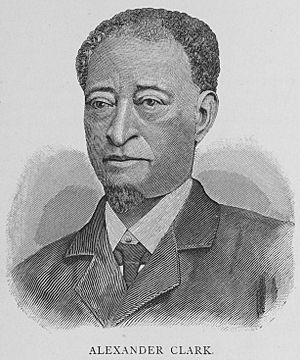

Alexander Clark facts for kids

Alexander G. Clark (born February 25, 1826 – died May 31, 1891) was an important African-American businessman and activist. He worked hard to gain equal rights for Black people in the United States. He even became a US Ambassador to Liberia in 1890. Clark is famous for winning a court case in 1868. This case allowed his daughter to attend a local public school in Muscatine, Iowa, regardless of her race. This happened 86 years before a similar national ruling called Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

Clark was also a leader in helping African Americans in Iowa get the right to vote. This right was granted through a state constitutional amendment in 1868. He was active in his church, Freemasonry, and the Republican Party. People called him "the Colored Orator of the West" because he was a great speaker. He earned a law degree and later became an editor of The Conservator newspaper. Clark died in Liberia, but his body was returned to Muscatine. His house there has been saved as a historic place.

Contents

Early Life of Alexander Clark

Alexander G. Clark was born in Washington, Pennsylvania, on February 25, 1826. His parents, John and Rebecca Clark, had been freed from slavery.

When he was about 13, Clark moved to Cincinnati, Ohio. He lived with his uncle, William Darnes, to learn how to be a barber. His uncle also made sure he got an education. Two years later, young Clark started working on a river steamboat called the George Washington.

Life in Muscatine, Iowa

In May 1842, at age 16, Clark settled in Muscatine, Iowa. This town, then called Bloomington, was on the Mississippi River. He worked as a barber and started his own businesses. He bought land and sold wood to steamboats. Being a barber helped him meet many important people in town.

Over the next 20 years, many other African Americans moved to this area. Muscatine was about 90 miles from the slave state of Missouri. It became a place where many Black people settled. Some were formerly enslaved people who escaped the South. Others came from free states in the East. Groups like the Quakers supported ending slavery.

After getting settled, Clark married Catherine Griffin in 1848. She had been freed from slavery in Virginia when she was three. The Clarks had five children. Rebecca, Susan, and Alexander G. Clark, Jr. lived to adulthood.

Also in 1848, Clark helped start the local African Methodist Episcopal Church in Muscatine. He helped buy land for their first church building, which was finished the next year. The AME church was the first independent Black church in the United States.

Clark became friends with the famous abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Clark was the Iowa agent for Douglass's newspaper, The North Star. He even attended a convention organized by Douglass in 1853. They stayed in touch for many years.

During the American Civil War (1861-1865), Clark helped recruit Black soldiers. He helped form the "60th Iowa Colored Troops." Nearly 1,100 Black men from Iowa and Missouri served in this regiment. Clark, at age 37, joined as a sergeant-major. However, he could not serve due to a physical issue.

Clark worked hard to improve civil rights for African Americans in Iowa and across the country. In 1855, he signed a petition asking the state to allow free Black people to move into Iowa. The law was not changed then, but more Black people moved to the area after the war. After the Civil War, Clark and Black veterans pushed the Iowa legislature for the right to vote. They won this right in 1868.

Clark's Fight for School Integration

In 1867, Clark sent his daughter Susan to a local public school in Muscatine. She was not allowed to attend because she was Black. Muscatine had a separate school for Black students. But it was about a mile from their house. Clark also felt the teachers there were not good enough.

So, in 1868, he sued the school board. He wanted his daughter to attend her local school. The local court agreed with him, but the school board appealed the decision.

The Iowa State Supreme Court also ruled in the Clarks' favor in April 1867. The court said that the Iowa Constitution required schools to educate "all the youths of the State." The court ruled that making Black students go to a separate school broke this law. Because of Clark's actions, Iowa was one of the first states to integrate its schools. This important state case was even mentioned by the US Supreme Court in its 1954 ruling for Brown v. Board of Education.

Clark's son, Alexander G. Clark Jr., was the first African American to earn a law degree from the University of Iowa in 1879. Alexander Clark Sr. also studied there and earned his law degree in 1884. They practiced law together for a time.

Politics, Publishing, and US Ambassador to Liberia

After the Civil War, Clark became very active in politics. He joined the Republican Party and Prince Hall Freemasonry. In 1869, he was a delegate to the Colored National Convention in Washington, D.C. He was part of a group that met with President Ulysses S. Grant. Clark was the spokesman for this group.

That same year, Clark was elected vice-president of the Iowa State Republican convention. In 1872, he was a delegate to the Republican National Convention. This convention nominated President Grant for re-election. Because he was such a good speaker, Clark became known as the "Colored Orator of the West." In 1873, President Grant offered him a job as consul to Aux Cayes, Haiti. But Clark turned it down because the pay was too low.

Clark later moved to Chicago. He had already invested in The Conservator, a newspaper started by Ferdinand L. Barnett in 1878. In the late 1880s, Clark bought the newspaper and became its editor.

President Benjamin Harrison appointed Clark as the U.S. Minister to Liberia on August 16, 1890. This was one of the highest jobs a US president had given to an African American at that time. President Harrison also appointed Clark's friend Frederick Douglass as U.S. Minister to Haiti. Clark died from a fever in Monrovia, Liberia, on May 31, 1891. His body was brought back to Muscatine and buried with honors in Greenwood Cemetery. His grave has a tall memorial stone.

Legacy and Honors

- The Alexander Clark House in Muscatine has been saved. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. A person named D. Kent Sissel bought and restored it. He has worked hard to share Clark's story.

- In 1977, a new tall building called Clark House was opened. It was named after Clark. This building was Muscatine's first high-rise to offer affordable housing for older people with lower incomes.

- The Alexander G. Clark Project has a website and Facebook page about Clark.

- The Alexander G. Clark Foundation works to keep Clark's legacy alive. They focus on preserving the Alexander Clark House.

- In 2018, the City of Muscatine started "Alexander Clark Day." It is celebrated every year on Clark's birthday, February 25.

- Also in 2018, a Muscatine museum had an exhibit. It celebrated 150 years since the Iowa Supreme Court's decision in favor of Susan Clark.

- In 2019, the Alexander Clark Room was dedicated. It is on the 6th floor of the Merrill Hotel in Muscatine. From its windows, you can see the Mississippi River and the historic neighborhood where the Clark family lived.

See Also

- Alexander Clark House, listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

- Clark v. Board of School Directors

Other reading

- Gallaher, Ruth A. "A Colored Convention," Palimpsest, Vol. II. State Historical Society of Iowa, May 1921. Iowa City, Iowa. pp. 178–81.

- Randall, J.J. Little Known Stories of Muscatine, Fairall Service. 1949. Muscatine, Iowa.

- Witter, F.M., Walton, Alice B., Walton, J.P., History of Muscatine County. Western Historical Society, 1879. Chicago. pp. 597–598.

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |