Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House facts for kids

|

U.S. Custom House

|

|

|

U.S. Historic district

Contributing property |

|

(2008)

|

|

| Location | 1 Bowling Green Manhattan, New York City |

|---|---|

| Built | 1901-1907 |

| Architect | Cass Gilbert, Daniel Chester French |

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts |

| Part of | Wall Street Historic District (ID07000063) |

| NRHP reference No. | 72000889 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | January 31, 1972 |

| Designated NHL | December 8, 1976 |

The Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House is a famous building in New York City. It was built between 1902 and 1907. A custom house is where the government collects taxes on goods brought into the country. This building was used for collecting these taxes for the Port of New York.

The building was designed by Cass Gilbert in a style called Beaux-Arts. It is located at 1 Bowling Green in the Financial District of Manhattan. This spot is very historic, as it was once home to Fort Amsterdam and Government House.

The idea for a new custom house came up in 1889. The old one was at 55 Wall Street. After some disagreements, the new building at Bowling Green was approved in 1899. Cass Gilbert won a competition to be the architect. The building opened in 1907. Later, in 1938, beautiful murals were added inside.

The United States Customs Service moved out of the building in 1974. It was empty for over ten years. Then, in the late 1980s, it was renovated. In 1990, the building was renamed to honor Alexander Hamilton. He was one of the Founding Fathers and the first Secretary of the Treasury.

Today, the building is home to the George Gustav Heye Center of the National Museum of the American Indian. This museum opened in 1994. It also houses the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York. Since 2012, the National Archives at New York City has also been there. The building is a very important landmark. It was named a city landmark in 1965 and a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

Where is the Custom House?

The Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House is on a unique plot of land. It is shaped like a trapezoid. Bowling Green is to its north. Whitehall Street is to the east, Bridge Street to the south, and State Street to the west.

The building is about 300 feet wide on Whitehall Street and State Street. The main side on Bowling Green is about 200 feet wide. The back side on Bridge Street is about 290 feet wide. Many other important buildings are nearby.

You can easily reach the Custom House by subway. The New York City Subway's Broadway Line (R and W train) and Lexington Avenue Line (4 and 5 train) run close by. There are subway entrances right next to the building.

This site is very old and important. It was where Fort Amsterdam was built by the Dutch. This fort was the start of the New Amsterdam settlement. New Amsterdam later grew into New York City. Bowling Green, the park in front, is the oldest park in New York City.

How the Custom House Looks

The Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House is seven stories tall. It has a steel frame inside. Cass Gilbert designed it in the Beaux-Arts style. This style combines architecture, engineering, and fine arts. Gilbert wanted the building's art to show "the commerce of ancient and modern times."

Many famous artists added sculptures, paintings, and decorations. These artists included Daniel Chester French, Karl Bitter, Louis Saint-Gaudens, and Albert Jaegers. Their works can be seen both inside and outside the building.

Outside the Building

Most custom houses face the water. But the Alexander Hamilton Custom House faces inland towards Bowling Green. There are six entrances. The main entrance is a wide staircase on the north side.

The first floor has large, rough-cut stone blocks. It is about 20 feet tall. The second, third, and fourth floors have columns in the Corinthian style. Some columns are paired, others are single. There are 44 columns in total.

The second floor is the piano nobile, meaning the main floor. Its windows are very fancy. They have carved heads above them. The windows on the third and fourth floors are simpler. This was common for Beaux-Arts buildings. They usually had more details on the lower, more visible parts.

The fifth floor has a decorative band with small rectangular windows. The sixth floor is right above it. The seventh floor is a red-slate mansard roof with dormer windows. It also has copper decorations.

Sculptures on the Exterior

The most famous sculptures are the Four Continents. They are located on the front steps. Daniel Chester French created these large marble statues. They show women representing Asia, America, Europe, and Africa. Each main figure also has smaller human figures next to her. Asia has a tiger, and Africa has a lion.

Above the main roofline, there are twelve standing sculptures. These represent seafaring nations. They show important trading cities from ancient times to modern history. Each statue is about 11 feet tall and weighs about 20 short tons. They are arranged in order from east to west, starting with ancient Greece and Rome. Eight different sculptors worked on these. One statue, Germania, was changed in 1918. It originally showed German symbols, but these were replaced with Belgian ones during World War I.

The tops of the 44 columns have carved heads. These show Hermes/Mercury, the god of trade. The windows on the main front have eight carved keystones. These show heads representing different human races. The city of New York's coat of arms is carved under the main entrance arch.

Inside the Building

Just inside the main entrance is a beautiful hallway. It has a rounded ceiling, marble columns, and colorful mosaics. Beyond bronze gates, you enter the Great Hall. In the center of the building is a large, round room called the rotunda. It rises up to the third floor.

Marble staircases with iron railings connect the different floors. There were also elevators in each corner of the building. When the building was first built, only the main rooms were decorated. These included the rotunda, hallways, lobby, and the collector's office. These areas had marble walls in different colors. They also had many decorations with a nautical, or sea-themed, design.

Ground Floor

The ground floor is about 20 feet tall. Near the south end, there was once a United States Postal Service office. Mail would arrive through delivery docks and be sorted in the basement. The floors, walls, and columns are made of marble. The ceilings are about 17 feet high.

In 2006, about 6,000 square feet of storage space under the rotunda was changed. It became the Heye Center's Diker Pavilion for Native Arts and Cultures. This pavilion is a circular space that can seat 400 people. It has a maple dance floor in the middle.

Second Floor

The second floor generally has a ceiling about 23 feet tall. It includes former office spaces, a lobby, and the rotunda. The architect, Gilbert, designed the inside to be very clear and easy to navigate. The George Gustav Heye Center of the National Museum of the American Indian now uses almost all of the second-floor space.

A long lobby crosses the northern part of the second floor. The floors have marble mosaic patterns. The doorways have carvings related to the sea. The ceilings have three large bronze lanterns. The lobby is made of marble. Semicircular staircases are at both ends of the lobby. Only the western staircase is open to the public.

The collector's office was in the northwestern corner of the second floor. It had fancy oak wood panels designed by Tiffany Studios. It also had hardwood floors and a decorated plaster ceiling. There were ten paintings above the wood panels showing 17th-century ports. This office is usually closed to the public but can be rented for events.

The rotunda is a large, oval-shaped room. It is about 85 by 135 feet. It rises up to the third story. The walls and floors are made of different colored marbles. The ceiling is special because it supports itself without any metal structure. It uses a system of fireproof tiles. In the center of the ceiling is a large oval skylight.

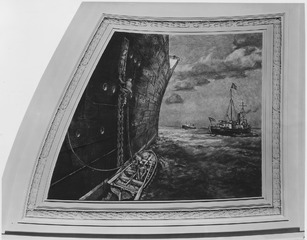

The underside of the ceiling has eight large panels. These panels have murals painted on them. These murals show shipping activity in the Port of New York and New Jersey. Reginald Marsh painted them in 1937. The rotunda can also be rented for special events.

- Rotunda murals

-

From left: Explorer Hudson, SS Washington Passing Ambrose Lightship, Explorer Block

-

From left: Explorer Verrazzano, Coast Guard Cutter Calumet Meeting the SS Washington, Explorer Columbus

Upper Stories

The upper stories have ceilings between 12 and 16 feet tall. All of these floors were used for office space. The outer part of the fifth floor was originally used for storing documents. This was because the windows on that floor were very small.

History of the Custom House

Before income taxes, the U.S. government got most of its money from import taxes. These taxes were collected at custom houses. In the 1800s, the Port of New York was the busiest port in the country. Because of this, the New York Custom House collected the most money. Until 1913, the New York Custom House provided two-thirds of the government's income! The person in charge of the New York Custom House even earned more than the U.S. president.

The New York Custom House moved several times before this building was constructed. It started in 1790 on South William Street. It moved to the site of Fort Amsterdam in 1799. The old building there was torn down in 1815. The custom house then moved to other places. Its last location before the Alexander Hamilton Custom House was at 55 Wall Street.

Planning the New Building

By 1888, the old custom house at Wall Street was in bad shape. It was "old, damp, ill-lighted, badly ventilated." People started thinking about a new building. In 1889, the Treasury secretary chose Bowling Green as the new site. But there were problems. Business people didn't want the custom house to move. A judge also ruled that the government couldn't just take the land.

It took a long time to get the money to buy the land at Bowling Green. By 1893, there wasn't enough money. The project stalled for several years. In 1897, a new law allowed private architects to design federal buildings. This helped move things forward.

Choosing an Architect

In 1897, Senator Thomas C. Platt and Representative Lemuel E. Quigg proposed bills for a new custom house. They wanted it at Wall Street. But these bills didn't pass. In 1898, they proposed bills to get the Bowling Green site. These bills passed in 1899. The government paid $2.2 million to the landowners. The old Custom House was sold for $3.21 million.

Twenty architecture firms were asked to submit designs in May 1899. The government wanted a building with a basement and up to six stories. A jury picked two finalists: Carrere & Hastings and Cass Gilbert. Gilbert was chosen, even though some people were against it. They thought he was too new to New York City. But his selection was confirmed in November 1899.

Building the Custom House

Work began in February 1900. Old buildings on the site were torn down. The ground was dug out very deep. It was called "the biggest hole that was ever made in this city." In December 1901, a contractor named John Peirce was hired to build the first floor.

The cornerstone of the building was placed on October 7, 1902. The ceremony was attended by the Treasury secretary. The cornerstone contained items from that time. Building the Custom House took a long time because of government rules, money problems, and supply shortages.

By February 1905, the building was about 70% finished. In 1906, a post office branch moved into the ground floor. This made it the first tenant. By September 1907, the Custom House was ready to open. The U.S. Customs Service moved its offices there on November 4, 1907. The total cost was about $4.5 million.

Life in the Custom House

After the Customs Service moved in, other government agencies also came. These included the Weather Bureau. By 1908, the building was full. In 1918, during World War I, all German symbols were removed from the sculptures. The Germania statue was changed to show Belgian symbols instead. The U.S. Passport Agency also moved into the building in 1919.

In 1937, during the Great Depression, new murals were added to the main rotunda. Reginald Marsh painted these beautiful scenes. Before this, the rotunda ceiling was plain white. By 1940, the building needed repairs. The collector asked for money, saying chairs were breaking and records were piled up. From 1914 to 1956, the building also had a tax office.

Later Years and Restoration

Moving Out and Renovating

By 1964, the U.S. Customs Service thought about moving to the World Trade Center. They moved there in 1973. The Custom House then had 1,375 employees. After they left, the building became empty and fell into disrepair. Paint peeled, and weeds grew outside.

A group called the Custom House Institute was formed in 1974 to save the building. The government said the building was "surplus," meaning it was available for other uses. An architect suggested turning the upper floors into offices and keeping the rotunda open. But this didn't happen. The Custom House Institute used the first floor, but the upper floors were empty.

In 1977, it was estimated that it would cost $24 million to fix the building. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan helped get funding for the renovation. In 1979, Congress approved $26.5 million for repairs, including restoring Marsh's murals. In 1983, plans were requested for how to use the building. Several ideas came up, including a Holocaust museum and a cultural center. The Holocaust museum was chosen, but it later moved to a different site.

A major renovation began in August 1984. It cost $18.3 million. The outside and important inside areas were cleaned and restored. Old office spaces were turned into courtrooms and offices. Fire safety, security, and air conditioning were also updated. The total project cost $60 million.

Becoming a Museum

By 1987, Senator Moynihan suggested giving the building to the Museum of the American Indian. This museum was in Upper Manhattan and needed a new home. There was some debate about where the museum should go. Finally, a compromise was reached in 1988. The Smithsonian would build its own museum in Washington, D.C. It would also take over the Heye collection and keep a museum in New York City at the Custom House. This plan became law in 1989.

In 1990, the building was officially renamed the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House. The George Gustav Heye Center of the National Museum of the American Indian opened in the Custom House in October 1994. Most of the building had been closed for 20 years. The Heye Center used the three lower stories. The United States bankruptcy court used two other stories.

During the September 11 attacks in 2001, the building was mostly unharmed. But debris from the collapse of the World Trade Center had to be cleaned up. In 2006, the museum expanded into part of the ground floor. Six years later, in 2012, the National Archives and Records Administration offices in New York also moved to the Custom House.

See also

In Spanish: Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House para niños

In Spanish: Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House para niños