American Civil War widows who survived into the 21st century facts for kids

The American Civil War was fought from 1861 to 1865. It's amazing to think that some people who were married to Civil War veterans lived into the 21st century! At least four women are known to have been widows of Civil War soldiers and were still alive after the year 2000. These women were born in the 1900s. They married their husbands when the women were young and the men were very old. This happened because of special pensions. These pensions were payments given to families of Civil War veterans. They were known to be very helpful financially. Some of these marriages were mainly for the pension money, while others were regular married couples.

Contents

Long-Living Civil War Widows

Here is a list of some of the Civil War widows who lived into the 21st century:

| Widow | Marriage | Husband | State | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Birth | Death | Age at marriage |

Name | Birth | Death | Age at marriage |

Allegiance | |||

| Year | Years after Civil War |

||||||||||

| Gertrude Janeway | 1909 | 2003 | 138 years | 18 | 1927 | John Janeway | 1845 | 1937 | 82 | Union | Tennessee |

| Alberta Martin | 1906 | 2004 | 139 years | 21 | 1927 | William Jasper Martin | 1845 | 1931 | 82 | Confederacy | Alabama |

| Maudie Hopkins | 1914 | 2008 | 143 years | 19 | 1934 | William M. Cantrell | 1847 | 1937 | 87 | Confederacy | Arkansas |

| Helen Viola Jackson | 1919 | 2020 | 155 years | 17 | 1936 | James Bolin | 1843 | 1939 | 93 | Union | Missouri |

Meet Helen Viola Jackson (1919–2020)

Quick facts for kids

Helen Viola Jackson

|

|

|---|---|

Helen Viola Jackson in 1955, in costume for the Webster County Centennial

|

|

| Born | August 3, 1919 Webster County, Missouri

|

| Died | December 16, 2020 (aged 101) |

| Spouse(s) |

James Bolin

(m. 1936; died 1939) |

Helen Viola Jackson was born on August 3, 1919, and passed away on December 16, 2020. She was the very last known widow of a Union soldier. She was also the last known widow of any Civil War veteran. Helen lived to be 101 years old.

In 1936, during the Great Depression, she married James Bolin. He was 93 years old, and she was 17. James Bolin had fought for the Union in the 14th Missouri Cavalry. Helen met him because her father asked her to help the elderly Mr. Bolin with chores. He had no other way to thank her. So, he offered to marry Helen. This way, she could get his pension after he died. Other similar marriages had happened before.

Helen and James got married outside his home in Niangua, Missouri. They kept their marriage a secret. Helen continued to live with her parents. After James died three years later, Helen decided not to apply for the monthly pension. She feared disapproval from James's daughters. The marriage was recorded in James's family Bible. Other documents also confirmed it. Helen did not tell anyone about her marriage until 2017. She was planning her funeral with her pastor. They then realized how important her long life and secret marriage were to history. Before this, Maudie Hopkins, who died in 2008, was thought to be the last surviving Civil War widow.

Helen never married again after James Bolin's death. She did not have any children. She was an important person in her community in Elkland, Missouri. In 2018, she was honored by being included in the Missouri Walk of Fame. This was two years before she passed away.

The last person to receive a Civil War pension was Irene Triplett. She was the daughter of a Civil War veteran. Irene passed away on May 31, 2020.

Meet Maudie Hopkins (1914–2008)

Maudie White Hopkins was born Maudie Cecelia Acklin on December 7, 1914. She died on August 17, 2008. Many believed she was the oldest surviving widow of a Confederate soldier. When she passed away, she was the oldest publicly known Civil War widow. However, some thought other widows might still be alive but unknown.

Maudie was born in Baxter County, Arkansas. She married William M. Cantrell on February 2, 1934. She was 19, and he was 86. Cantrell had joined the Confederate Army when he was 16. He served in General Samuel G. French's Battalion of Virginia Infantry. He was captured in 1863 but later exchanged. His first wife had died in 1929. William supported Maudie with a pension of $25 every two or three months. She inherited his home when he died in 1937. She did not receive any more pension money after his death. She remarried later in 1937, and then again after that. She had three children.

It was not unusual for young women in Arkansas to marry Confederate pensioners. In 1937, Arkansas passed a law. It said that women who married Civil War veterans would not get a widow's pension. This law was changed in 1939. It then said that widows born after 1870 were not eligible for pensions. Maudie usually kept her first marriage a secret. She worried that talk about her marrying a much older man would cause problems for her.

After looking at records from Arkansas and the United States Census Bureau, Maudie Hopkins was confirmed by several historical groups. The United Daughters of the Confederacy was one of the most important. A spokeswoman for this group said there might be two other widows. One was in Tennessee and another in North Carolina. If they were still alive, they chose to remain private.

Maudie Hopkins died on August 17, 2008. She was in a nursing home in Lexa, Arkansas, and was 93 years old.

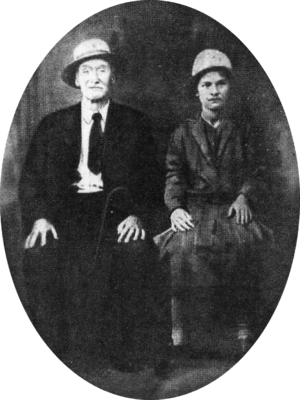

Meet Alberta Martin (1906–2004)

|

Alberta Martin

|

|

|---|---|

| Born |

Alberta Stewart

December 4, 1906 |

| Died | May 31, 2004 (aged 97) |

| Spouse(s) |

Howard Farrow

(m. 1925; died 1926)William Jasper Martin

(m. 1927; died 1931)Charlie Martin

(m. 1931; died 1983) |

| Children | 1 (from Farrow); 1 (from W. J. Martin) |

Alberta Martin was born Alberta Stewart on December 4, 1906. She died on May 31, 2004. People once thought she was the last living widow of a Confederate soldier. She is also believed to be the last widow whose marriage to a Civil War soldier resulted in children.

She was born to sharecropper parents in Danleys Crossroads, Alabama. This was a small sawmill town south of Montgomery. People often called her "Miz Alberta." Her mother passed away from cancer when Alberta was 11. Alberta left school after 7th grade. She went to work in cotton and peanut fields and in a cotton mill. At 18, she married a cabdriver named Howard Farrow. They had a son together. Howard Farrow died in a car accident in 1926.

After moving to Opp, Alabama, she met William Jasper Martin. He was a widower born in 1845. He was a veteran of the 4th Alabama Infantry, a Confederate unit during the Civil War. On December 10, 1927, Alberta Stewart, then 21, married William Jasper Martin, who was 81. She mainly married him to get help raising her son. Also, his $50 per month Confederate pension check gave her some financial security. She gave birth to a second son, Willie Martin. This was 10 months after her wedding to William Jasper Martin. He was 82 when their child was born. William Jasper Martin died in 1931.

Two months after her second husband's death, Alberta Martin married Charlie Martin. Charlie was William Jasper Martin's grandson from a much earlier marriage. Alberta and Charlie Martin were married for over fifty years. He died in 1983. After that, she moved to Elba, Alabama.

Alberta Martin lived a quiet life for most of her years. But she started getting attention from the media in the 1990s. In her last years, she became a symbol for the Sons of Confederate Veterans. She appeared at some of their events. The state of Alabama had stopped giving pension checks to Confederate widows. They thought all of them had passed away. But with help from the Sons of Confederate Veterans, Alberta began receiving a Confederate widow's pension in 1996. She also received payments for past years.

In 1996, two members of the Sons of Confederate Veterans visited her. They saw she lived without air-conditioning. They decided to help her get a Confederate widow's pension.

She seemed to enjoy the attention from the media. She attended many Civil War re-enactments and other events as a special guest. She spent her final years in a nursing home. Her care was paid for by various supporters. She died from a heart attack at 97 on May 12, 2004. Alberta, who had been widowed three times, had an "1860s style ceremony." She received full honors as the widow of a Confederate veteran. Her son William survived her but passed away in 2005. She was also featured in a chapter of the book Confederates in the Attic.

Meet Gertrude Janeway (1909–2003)

Gertrude Janeway was born Gertrude Grubb on July 3, 1909. She passed away on January 17, 2003. She was born in Blaine, Tennessee. Her parents were Thomas Bradshaw Grubb and Halley J. Townsley Grubb. John Janeway, an officer in the 14th Illinois Cavalry, started courting her when she was 16. Her mother, who was a widow, would not let her marry until she was 18. Gertrude married John Janeway in 1927. She was 18, and he was 81. The wedding ceremony took place in the middle of a dirt road. Family and friends were there. They lived together in a log cabin in Blaine, Tennessee. They stayed there until John Janeway's death in 1937.

On January 31, 1940, "Gertie" Janeway married Alfred Vineyard in Grainger County, Tennessee. In 1943, Gertrude divorced Alfred Vineyard. She then went back to using the name Gertrude Janeway.

She was a member of the Green Acres Missionary Baptist Church. Gertrude continued to live in the log cabin for almost 70 years after her husband's death. She received a $70 pension check for veterans' benefits from the government every two months. She received these payments until her death in 2003.

On April 9, 2011, The Economist newspaper wrote about her. They used her as an example of how long pension payments can last. They said that when Gertrude Janeway died in 2003, she was still getting a monthly check for $70. This was from the Veterans Administration. It was for a military pension earned by her late husband, John. He fought for the Union side in the American Civil War, which ended in 1865. The couple had married in 1927. He was 81, and she was 18. The amount was small, but the payment lasted for three centuries. This shows how long pension promises can continue.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |