André Kertész facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

André Kertész

|

|

|---|---|

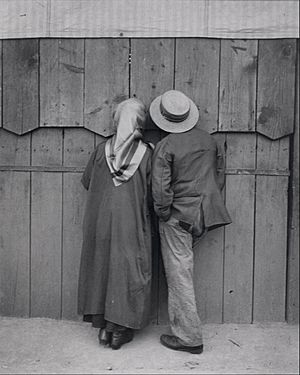

Kertész in New York, 1982

|

|

| Born |

Andor Kertész

2 July 1894 |

| Died | September 28, 1985 (aged 91) New York City, U.S.

|

| Occupation | Photographer |

| Spouse(s) |

|

André Kertész (born Andor Kertész; 2 July 1894 – 28 September 1985) was a famous photographer from Hungary. He is known for his new ideas in photo composition (how a picture is arranged) and for creating photo essays. A photo essay is a story told mostly through pictures.

When he started, his unique camera angles and style were not very popular. Kertész felt he never got the fame he deserved during his life. But today, he is seen as one of the most important photographers of the 1900s.

His family wanted him to be a stockbroker, but Kertész taught himself photography. His early photos were mostly printed in magazines, which were very popular back then. He served a short time in World War I. In 1925, he moved to Paris, France, which was a big center for art at the time. There, he worked for VU, France's first magazine with lots of pictures. He became successful and was involved with many young artists and the Dada art movement.

In 1936, Kertész moved to the United States because of the threat of World War II and the persecution of Jewish people in Europe. He had to start over and build his reputation again by taking photos for different jobs. In the 1940s and 1950s, he stopped working for magazines and became more famous around the world. His career is often divided into four parts: the Hungarian period, the French period, the American period, and the International period (at the end of his life).

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Learning

Andor Kertész was born on July 2, 1894, in Budapest, Hungary. His family was Jewish and middle-class. His father, Lipót Kertész, was a bookseller. Andor, who his friends called "Bandi," was the middle of three sons.

When his father died in 1908, his uncle, Lipót Hoffmann, helped the family. They moved to his uncle's country home in Szigetbecse. Kertész grew up in a calm, country setting, which later influenced his photography.

His uncle paid for him to study business, and he graduated in 1912. He then got a job at the stock exchange. But Kertész was not very interested in business. He loved illustrated magazines, fishing, and swimming in the Danube River.

Kertész was inspired by magazine photos and decided to learn photography. He was also influenced by paintings and poetry.

Hungarian Photography Period

In 1912, Kertész bought his first camera, an ICA box camera, even though his family wanted him to stay in business. In his free time, he took pictures of local farmers, gypsies, and the beautiful Hungarian Plains. His first photo is thought to be Sleeping Boy, Budapest, 1912.

His photos were first published in 1917 in the magazine Érdekes Újság, while he was serving in the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I. By 1914, his unique and mature style was already clear.

In 1914, at age 20, he was sent to the war front. He took photos of life in the trenches with a small camera. Many of these photos were lost during the Hungarian Revolution of 1919. In 1915, he was wounded by a bullet and his left arm was temporarily paralyzed.

He recovered in a military hospital in Budapest and then in Esztergom, where he kept taking pictures. One famous photo from this time is Underwater Swimmer, Esztergom, 1917. It shows a swimmer's body distorted by the water. Kertész later explored this idea more in his "Distortions" photos in the 1930s.

Kertész did not return to combat. After the war ended in 1918, he went back to the stock exchange. There, he met Erzsebet Salomon (later Elizabeth Saly), who became his future wife. He often used Elizabeth as a model for his photos. He also took many pictures of his brother Jenő.

In the early 1920s, Kertész tried farming and beekeeping, but this didn't last long because of political problems. After returning to the stock exchange, Kertész wanted to move to France to study photography. His mother convinced him to wait a few years. He worked at the exchange during the day and took photos in his free time.

In 1923, the Hungarian Amateur Photographer's Association offered him a silver award for a photo. But he had to print it using a special process he didn't like, so he turned down the medal. He received a diploma instead. On June 26, 1925, the Hungarian news magazine Érdekes Újság used one of his photos on its cover, making him well-known. By then, Kertész was determined to go to Paris and join its art scene.

French Photography Period

Kertész moved to Paris in September 1925. He left behind his family, including his fiancée Elizabeth. Elizabeth later followed him to Paris when he was more settled. Many Hungarian artists moved to Paris during this time, like Robert Capa and Brassaï. Other photographers like Man Ray also came to Paris.

At first, Kertész took photos for different European magazines. His work was published in Germany, France, Italy, and Great Britain. Soon after arriving in Paris, he changed his first name to André. In Paris, he became successful and well-known.

In 1927, Kertész was the first photographer to have his own exhibition (a show of his work). Jan Slivinsky showed 30 of his photos at the "Sacre du Printemps Gallery." Kertész became friends with artists in the growing Dada art movement, which challenged traditional art.

Over the next few years, Kertész had many solo and group shows. In 1932, his photos were sold for $20 each at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York. This was a lot of money during the Great Depression.

Kertész became friends with other Hungarian artists. He was interested in Cubism, an art style that used geometric shapes. He took portraits of famous painters like Piet Mondrian and Marc Chagall, writer Colette, and filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein. In 1928, he started using a Leica camera, which was smaller and easier to use. This was a very busy time for him; he took photos every day, both for magazines and for his own art. In 1930, he won a silver medal for his photography in Paris.

Kertész's photos were published in French magazines like Vu and Art et Médecine. He worked closely with Lucien Vogel, the editor of Vu. Vogel published Kertész's photos as "photo essays," allowing Kertész to tell stories with his pictures.

In 1933, Kertész was asked to create a series called Distortion. He took about 200 photos of two models, Najinskaya Verackhatz and Nadia Kasine. Their reflections were caught in special distortion mirrors, like those you might see at a carnival. In some photos, only parts of their bodies were visible in the reflection. Later that year, Kertész published a book of these photos called Distortions.

In 1933, Kertész published his first personal photo book, Enfants (Children). He dedicated it to his fiancée Elizabeth and his mother, who had passed away that year. He published more books in the following years: Paris (1934), Nos Amies les bêtes (Our Friends the Animals) in 1936, and Les Cathédrales du vin (The Cathedrals of Wine) in 1937.

Marriage and Family

In the late 1920s, Kertész secretly married a French photographer named Rosza Klein (also known as Rogi André). This marriage was very short, and he rarely spoke about it.

In 1930, he visited his family in Hungary. Elizabeth followed him to Paris in 1931, even though her family didn't want her to. Elizabeth and André stayed together for the rest of their lives. Kertész married Elizabeth on June 17, 1933. People said he spent less time with his artist friends after he got married.

In 1936, they moved to New York. They became US citizens within ten years. Elizabeth started a successful cosmetics business. She passed away from cancer in 1977.

Moving to America

As tensions grew in Europe with the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany, many magazines focused on political stories. They stopped publishing Kertész's photos because his subjects were not political. With less work and increasing persecution of Jewish people, Kertész and Elizabeth decided to move to New York. He was offered a job at the Keystone photo agency. In 1936, Kertész and Elizabeth sailed to Manhattan.

They arrived in New York on October 15, 1936. Kertész hoped to become famous in America, but life there was harder than he expected. He later called this time an "absolute tragedy." He missed his artist friends and found that Americans didn't like having their photos taken on the street.

Soon after arriving, Kertész met Beaumont Newhall, who was in charge of photography at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Newhall was preparing a photo show. Kertész offered some of his Distortions photos, and Newhall did show them. In December 1937, Kertész had his first solo show in New York.

The Keystone agency wanted him to work only in their studio, but Kertész preferred to photograph outside. He tried to go back to France for a visit, but he didn't have enough money. By the time he saved up, World War II had started, making travel to France almost impossible. It was also hard for him to learn English after learning French in Paris. Not speaking English well made him feel even more like an outsider.

Frustrated, Kertész left Keystone in 1937. He took jobs for magazines like Harper's Bazaar and Town and Country. He also worked for Life magazine. But he didn't like the rules and limits they put on his photography. For example, when asked to photograph tugboats, he also photographed the whole harbor, and Life refused to publish those extra photos.

In 1938, Look magazine published some of his photos but wrongly gave credit to his old boss. Kertész was very angry and thought about never working with photo magazines again. He also had problems with Coronet and Vogue magazines.

In 1941, Kertész and Elizabeth were called "enemy aliens" because Hungary was fighting with Germany in World War II. Kertész was not allowed to photograph outdoors or work on anything related to national security. To avoid problems, Kertész stopped taking commissioned jobs for three years.

On January 20, 1944, Elizabeth became a US citizen, and Kertész became one on February 3. Kertész started getting commissioned work again. In June 1944, László Moholy-Nagy offered him a job teaching photography, but Kertész turned it down.

In 1945, Kertész released a new book called Day of Paris, with photos he took before leaving France. It was very popular. Elizabeth's cosmetics business was doing well, so in 1946, Kertész signed a long-term contract with House and Garden magazine. This job limited his artistic freedom and required many hours in the studio, but he earned at least $10,000 a year, which was good pay. He also got his photo negatives back after six months.

Kertész photographed many famous homes and places, and he traveled to England, Budapest, and Paris, where he reconnected with old friends. From 1945 to 1962, House and Garden published over 3,000 of his photos, and he became very respected in the industry. But he had little time for his own artistic work, which made him feel limited.

Later Life

In 1946, Kertész had a solo exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago showing photos from his Day of Paris series. Kertész said this was one of his best times in the United States. In 1952, he and his wife moved to an apartment on the 12th floor near Washington Square Park in New York City. This park became the subject of some of his best photos in the US. He used a telephoto lens to take pictures of the park covered in snow, showing many shapes and tracks.

In 1955, he was upset when his work was not included in a famous photo show called The Family of Man at MoMA. Despite the success of his Chicago show, Kertész didn't have another exhibition until 1962. Kertész lived near the Twin Towers as they were being built and opened. He photographed them many times from his apartment before he died.

International Recognition Period

In late 1961, Kertész ended his contract with Condé Nast Publishing after a small disagreement. He started focusing on his own artistic work again. This later part of his life is called the "International period" because he became famous worldwide and his photos were shown in many countries.

In 1962, his work was shown in Venice, Italy. In 1963, he won a gold medal for his contributions to photography there. Later in 1963, his work was shown in Paris at the Bibliothèque nationale de France. He also visited Argentina to see his younger brother Jenő for the first time in years. Kertész tried taking color photos, but he only made a few.

In 1964, John Szarkowski, the new photography director at the Museum of Modern Art, gave Kertész a solo show. With his work praised by critics, Kertész was finally recognized as an important artist in the photography world.

Kertész's work was shown in many exhibitions around the world, even when he was in his early nineties. Because of his new success, in 1965, Kertész became a member of the American Society of Media Photographers.

He received many awards quickly. In 1974, he got a Guggenheim Fellowship. He also received the French Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (Order of Arts and Letters) and the Mayor's Award of Honor for Arts and Culture in New York. In 1980, he received the Medal of the City of Paris. In 1981, he received an honorary doctorate from Bard College.

During this time, Kertész published several new books. He was also able to get back some of the photo negatives he had left in France decades earlier.

Despite his successes, Kertész still felt he wasn't fully recognized as a photographer. In his last years, he traveled around the world for his exhibitions, especially to Japan. He also reconnected with other artists. After his wife died in 1977, Kertész relied on his new friends, often visiting them to talk. By this time, he had learned basic English and spoke in what his friends called "Kertészian," a mix of Hungarian, English, and French.

In 1979, the Polaroid Corporation gave him one of their new SX-70 cameras, which he experimented with into the 1980s. His fame continued to grow. In 1982, he received the National Grand Prize of Photography in Paris and the 21st Annual George Washington Award from the American Hungarian Foundation.

In 1980, Kertész was the subject of a large portrait project by Canadian artist Arnaud Maggs, called André Kertész, 144 Views. Kertész called it a "portrait mosaic."

Death

André Kertész died peacefully in his sleep at home on September 28, 1985. He was cremated, and his ashes were buried with his wife's.

Legacy and Honors

- 1983: Honorary doctorate from the Royal College of Art; and the title of Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honor) in Paris. He also received an apartment for future visits to the city.

- 1984: The Maine Photographic Workshop's first Annual Lifetime Achievement Award.

- 1984: The Metropolitan Museum of Art bought 100 of his prints, which was their largest purchase of work from a living artist.

- 1985: Californian Distinguished Career in Photography Award.

- 1985: First Annual Master of Photography Award, given by the International Center of Photography.

- 1985: Honorary doctorate from Parson's School of Design.

- 1986: Kertész was added to the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum after his death.

- 2002: A New York City photograph by Kertész appeared on a 37-cent U.S. postage stamp, as part of a series called "Masters of American Photography."

Critical Evaluation

For most of his career, Kertész was seen as a "hidden hero" of photography. He worked behind the scenes but was rarely given credit for his work, even until his death in 1985. Kertész felt unrecognized throughout his life, even though he always sought acceptance and fame.

Although he received many awards, he never felt that his style and work were truly accepted by art critics and audiences. In 1927, he was the first photographer to have a solo exhibition. But Kertész said it wasn't until his 1946 exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago that he felt he received good reviews. He often called this show one of his best moments in America.

During his time in America, he was described as an "intimate artist," meaning his photos made viewers feel close to the subject, even when it was a big city like New York. Even after his death, his reproduced work received good reviews. People said, "Kertész was above all a consistently fine photographer."

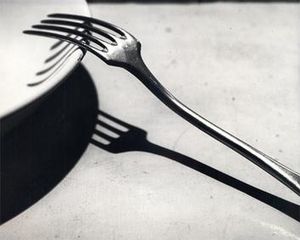

Kertész's work often uses light in special ways. He himself said, "I write with light." He didn't try to "comment" on his subjects but simply captured them. This is often why his work was sometimes overlooked; he didn't follow any political ideas and offered no deep messages in his photos, just the simple beauty of life. His art felt personal and nostalgic, giving his images a timeless quality that was truly recognized only after his death. Unlike other photographers, Kertész's work showed a timeline of his life, like his many photos from Parisian cafés where he spent time waiting for inspiration.

While Kertész rarely received bad reviews, the lack of strong commentary made him feel distant from true recognition. Today, however, he is often called the "father of photojournalism." Other photographers, like Henri Cartier-Bresson, said in the 1930s, "We all owe him a great deal." When he was 90 years old, someone asked him why he was still taking photos. He replied, "I'm still hungry."

See Also

In Spanish: André Kertész para niños

In Spanish: André Kertész para niños

- Kertész (crater), named after him

Images for kids

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |