Antonin Artaud facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Antonin Artaud

|

|

|---|---|

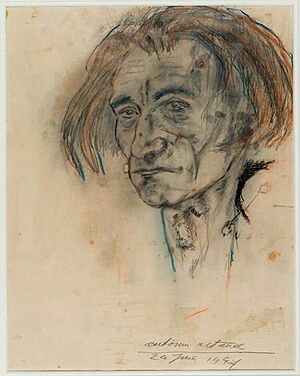

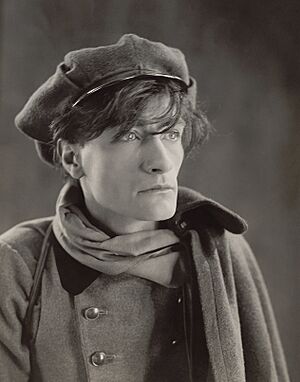

Artaud in 1926

|

|

| Born |

Antoine-Marie-Joseph Artaud

4 September 1896 Marseille, France

|

| Died | 4 March 1948 (aged 51) Ivry-sur-Seine, France

|

| Resting place | Saint-Pierre Cemetery, Marseille |

| Education | Collège du Sacré-Cœur |

| Occupation |

|

| Known for |

|

|

Notable work

|

The Theatre and Its Double |

Antonin Artaud (born Antoine Marie Joseph Paul Artaud; 4 September 1896 – 4 March 1948) was a French artist. He worked in many different areas, including writing, theatre, and cinema. He is famous for his ideas about the Theatre of Cruelty, which greatly influenced theatre in the 1900s. His work was often intense and unique. It explored ideas from old cultures, philosophy, and spiritual practices from places like Mexico and Bali.

Early Life

Antonin Artaud was born in Marseille, France. His parents were Euphrasie Nalpas and Antoine-Roi Artaud. Both of his grandmothers were sisters from Smyrna (now İzmir, Turkey). His family background, especially his Greek roots, was important to him throughout his life. Artaud was one of nine children, but sadly, four were stillborn and two others died young.

When he was five, Artaud became very ill. Some people thought he had meningitis, a serious brain infection. However, some experts now believe it might have been a different illness.

Artaud went to Collège Sacré-Coeur, a Catholic school, from 1907 to 1914. There, he started reading books by famous writers like Arthur Rimbaud and Edgar Allan Poe. He also started a small literary magazine with his friends.

Towards the end of his time at school, Artaud became very quiet and stopped spending time with others. He even destroyed most of his writings and gave away his books. Because his parents were worried, they arranged for him to see a doctor who specialized in mental health. For the next five years, Artaud spent time in special care facilities to help with his health.

In 1916, Artaud was called to join the French Army. However, he was released early due to health reasons. He later said it was because he walked in his sleep, while his mother said it was due to his "nervous condition." In March 1921, he moved to Paris and continued to receive medical care from Dr. Édouard Toulouse.

Career

Theatre Work

In Paris, Artaud worked with many well-known French theatre directors. These included Jacques Copeau and Charles Dullin. One director, Lugné-Poe, who gave Artaud his first professional theatre job, once said Artaud was "a painter lost in the midst of actors."

Artaud learned a lot about theatre while working with Dullin's group, Théâtre de l'Atelier, starting in 1921. He trained for many hours each day. Artaud admired Dullin's teaching and shared his interest in theatre from East Asia, especially Bali and Japan. He felt he was "rediscovering ancient secrets" through Dullin's lessons. However, they later had disagreements about how Eastern and Western theatre styles differed. Artaud left Dullin's group in 1923.

After that, he joined another theatre group led by Georges and Ludmilla Pitoëff. He stayed with them for about a year before focusing more on working in cinema.

Writing Career

In 1923, Artaud sent some poems to La Nouvelle Revue Française (NRF), a famous French literary magazine. The poems were not published, but the editor, Jacques Rivière, found Artaud interesting. They started writing letters to each other, which became Artaud's first major published work, Correspondance avec Jacques Rivière.

Artaud continued to publish important writings in the NRF. Later, he put many of these texts into his famous book, The Theatre and Its Double. This book included his ideas for the "First Manifesto for a Theatre of Cruelty" (1932) and "Theatre and the plague" (1933).

Work in Cinema

Artaud was also active in cinema as a critic, actor, and writer. He acted in several films, including playing Jean-Paul Marat in Abel Gance's Napoléon (1927) and the monk Massieu in Carl Theodor Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928).

Artaud wrote ten film scripts that still exist today. Only one of them, The Seashell and the Clergyman (1928), was made into a film during his lifetime. Many people consider it the first surrealist film, though Artaud had mixed feelings about the final movie.

Connection with Surrealists

Artaud was briefly connected with the Surrealists, a group of artists who explored dreams and the unconscious mind. However, he was later asked to leave the group by André Breton in 1927. This was partly because the Surrealists were becoming more involved with the Communist Party in France. Also, Breton started to dislike theatre, seeing it as too traditional and not revolutionary enough.

In his writing "The Manifesto for an Abortive Theatre" (1926/27), Artaud criticized the Surrealists. He called for a deeper change in society, beyond what he saw as their less active approach.

Théâtre Alfred Jarry (1926–1929)

In 1926, Artaud, Robert Aron, and Roger Vitrac (who had also left the Surrealists) started the Théâtre Alfred Jarry (TAJ). They put on four plays between 1927 and 1929. Even though the theatre didn't last long, many famous European artists came to see their shows.

Paris Colonial Exposition (1931)

In 1931, Artaud saw Balinese dance performances at the Paris Colonial Exposition in Paris. Even though he didn't fully understand everything he saw, it greatly influenced his ideas for theatre. He was especially impressed by the "hypnotic" rhythms of the Balinese music (called gamelan) and how the dancers' movements worked with the music.

The Cenci (1935)

In 1935, Artaud put on his own version of Percy Bysshe Shelley's play The Cenci in Paris. This was Artaud's only chance to stage a play using his ideas for the Theatre of Cruelty. The play had a set designed by Balthus and used new sound effects, including the Ondes Martenot, an early electronic instrument. However, the play was not a financial success.

Shelley's original play focused on the feelings of the character Beatrice. Artaud's version, however, highlighted the play's harshness and violence, especially its themes of revenge and family murder. Artaud's stage directions for the opening scene showed his style. He described it with strong wind, loud sounds, crowds of figures, church bells, and large mannequins.

One expert, Jane Goodall, noted that Artaud's version focused more on action than thinking, making the events move quickly. Another expert, Adrian Curtin, pointed out how important the sounds were in the play, not just as background but as something that helped drive the story.

The Theatre and its Double (1938)

In 1938, Artaud published The Theatre and Its Double, one of his most important books. In this book, he suggested a type of theatre that went back to old rituals and magic. He wanted to create a new theatre language using symbols and movements, a language of space without much talking. This language would appeal to all the senses.

He believed his Theatre of Cruelty would move away from traditional stages and the main role of the playwright. He thought these things stopped the "magic of genuine ritual." Instead, he wanted to use "violent physical images" that would "crush and hypnotize" the audience, making them feel caught up "as by a whirlwind of higher forces."

Travels and Health

Journey to Mexico

In 1935, Artaud decided to travel to Mexico. He believed there was a strong movement there to return to older ways of life, before the arrival of the Spanish. He received a travel grant and left for Mexico in January 1936. After arriving, Artaud became a known figure in the Mexican art scene. He also spent time in Norogachic, a Rarámuri village. He said he took part in peyote ceremonies, though some experts have questioned this.

Ireland and Return to France

In 1937, Artaud returned to France. A friend gave him a special walking-stick that Artaud believed was a sacred Irish relic with magical powers. Artaud traveled to Ireland, perhaps to return the staff. He spoke very little English and no Gaelic, so he found it hard to communicate. In Dublin, he ran out of money and stayed in places for the homeless. After some arguments with the police, he was arrested. Before being sent back to France, he was briefly held in Mountjoy Prison. Irish government papers stated he was deported as "a destitute and undesirable alien."

On his way back to France, Artaud believed he was being attacked by two crew members on the ship. He fought back and was put in a straitjacket. When he arrived in France, the police took him to a psychiatric hospital. Artaud spent the rest of his life moving between different institutions, depending on his health and world events.

In Rodez

In 1943, during World War II, Artaud was moved to a psychiatric hospital in Rodez, France. There, he was cared for by Dr. Gaston Ferdière. At Rodez, Artaud received treatments, including electroshock therapy and art therapy. The doctor thought Artaud's habits of making magic spells and drawing unusual images were signs of mental illness. Artaud disliked the electroshock treatments and asked for them to stop. However, he also said they helped him feel more like himself again. During this time, Artaud started writing and drawing again after a long break. In 1946, Dr. Ferdière released Artaud to his friends, who placed him in a clinic in Ivry-sur-Seine.

Final Years

At the Ivry-sur-Seine clinic, Artaud's friends encouraged him to write. He also visited an art exhibition of Vincent van Gogh's work in Paris.

Pour en Finir avec le Jugement de Dieu

Artaud recorded his radio play, Pour en Finir avec le Jugement de Dieu (To Have Done With the Judgment of God), in November 1947. This work stayed true to his vision for the theatre of cruelty, using "screams, rants and vocal shudders." The director of French Radio, Wladimir Porché, stopped the broadcast the day before it was supposed to air in February 1948. This was partly because of its strong language and anti-religious ideas. It also included a mix of xylophone sounds, percussion, cries, screams, and other noises.

A panel of about 50 artists, writers, and journalists listened to the work privately. Most of them wanted it to be broadcast. However, Porché still refused. The work was not publicly heard until 1964, when a radio station in Los Angeles played an unauthorized copy. The first time it was broadcast on French radio was 20 years after it was made.

Death

In January 1948, Artaud was diagnosed with colorectal cancer. He passed away on 4 March 1948, at a psychiatric clinic in Ivry-sur-Seine, near Paris.

Legacy and Influence

Artaud has had a big impact on theatre, modern art, literature, and other fields.

Theatre and Performance

Many of Artaud's works were not performed for the public until after he died. For example, his play "Spurt of Blood" (1925) was first performed in 1964. Despite this, he greatly influenced the development of experimental theatre and performance art. Susan Sontag, a famous writer, said that Artaud's impact on Western theatre was so deep that theatre history could be divided into "before Artaud and after Artaud."

Many artists have said Artaud influenced their work, including Peter Brook, Sam Shepard, and Allen Ginsberg.

His influence can be seen in:

- Jean-Louis Barrault's play The Trial (1947).

- The Theatre of the Absurd, especially plays by Jean Genet and Samuel Beckett.

- Peter Brook's play Marat/Sade in 1964.

- The Living Theatre, an experimental theatre group.

- In Canada, playwright Gary Botting created plays with Artaud's ideas.

- Charles Marowitz's play Artaud at Rodez is about Artaud's time in the Rodez hospital.

Philosophy

Artaud also influenced philosophers. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari used Artaud's phrase "the body without organs" in their philosophical ideas. Philosopher Jacques Derrida also wrote important works about Artaud.

Literature

Poet Allen Ginsberg said Artaud's work, especially "To Have Done with the Judgement of God," had a huge influence on his famous poem "Howl". The novel Yo-Yo Boing! by Giannina Braschi includes a discussion about Artaud's many talents. A new novel series about Artaud's life and his friendship with poet Robert Desnos began in 2023.

Music

The band Bauhaus has a song about him called "Antonin Artaud." The Argentine hard rock band Pescado Rabioso released an album titled Artaud, with lyrics partly based on Artaud's writings. The Venezuelan rock band Zapato 3 also has a song named "Antonin Artaud."

Composer John Zorn has written many musical pieces inspired by Artaud, including seven CDs and other works for violin, piano, and orchestra.

Film

Filmmaker E. Elias Merhige said Artaud was a key influence for his experimental film Begotten. There is also a documentary about him called "La Véritable Histoire d'Artaud le Mômo."

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Director | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1923 | Fait-divers | Monsieur 2 | Autant-Lara | |

| 1925 | Surcouf | Jacques Morel, a traitor | Luitz-Morat | |

| 1926 | Graziella | Cecco | Marcel Vandal | |

| 1926 | Le Juif Errant | Gringalet | Luitz Morat | |

| 1927 | Napoléon | Marat | Abel Gance | |

| 1928 | The Passion of Joan of Arc | Massieu | Carl Dreyer | |

| 1928 | Verdun: Visions of History | Paul Amiot | Léon Poirier | |

| 1928 | L'Argent | Secretary Mazaud | Marcel L'Herbier | |

| 1929 | Tarakanova | Le jeune tzigane | Raymond Bernard | |

| 1931 | La Femme d'une nuit | A traitor | Marcel L'Herbier | |

| 1931 | Montmartre | Unidentified | Raymond Bernard | |

| 1931 | L'Opéra de quat'sous | A Thief | G. W. Pabst | |

| 1932 | Coups de feu à l'aube | Leader of a group of assassins | Serge de Poligny | |

| 1932 | Les Croix de bois | A delirious soldier | Raymond Bernard | |

| 1932 | L'enfant de ma soeur | unidentified role | Henri Wullschleger | |

| 1933 | Mater Dolorosa | Lawyer | Abel Gance | |

| 1934 | Liliom | Knife-seller | Fritz Lang | |

| 1934 | Sidonie Panache | Emir Aba-el Kadcr | Henri Wullschleger | |

| 1935 | Lucrezia Borgia | Savonarola | Abel Gance | |

| 1935 | Koenigsmark | The Librarian | Maurice Tourneur |

See also

In Spanish: Antonin Artaud para niños

In Spanish: Antonin Artaud para niños