Arius facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Arius

|

|

|---|---|

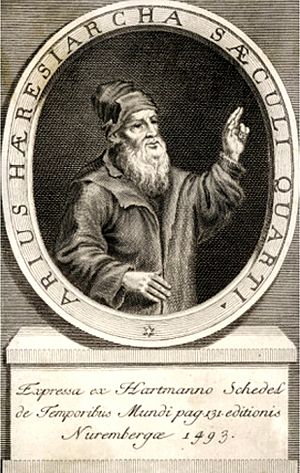

Arius arguing for the supremacy of God the Father, and that the Son had a beginning as a true Firstborn

|

|

| Born | 256 |

| Died | 336 (aged 80) |

| Occupation | Presbyter |

|

Notable work

|

Thalia |

| Theological work | |

| Era | 3rd and 4th centuries AD |

| Language | Koine Greek |

| Tradition or movement | Arianism |

| Notable ideas | Subordinationism |

Arius (born around 250 or 256 AD, died 336 AD) was a Christian priest from Cyrenaica (modern-day Libya). He is famous for his teachings known as Arianism. These ideas were about the nature of God and Jesus. Arius believed that God the Father was unique and that Jesus Christ the Son was not equal to the Father. He taught that Jesus was created by God and had a beginning.

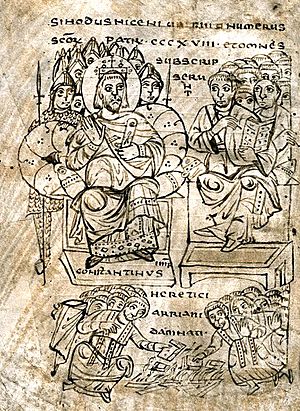

His ideas were very different from what most Christians believed. This led to a big debate in the early Christian Church. Emperor Constantine the Great called the First Council of Nicaea in 325 AD to try and settle these disagreements. At this council, the main belief that Jesus and God the Father were "of one essence" (meaning they were equally divine and eternal) became the official view. Those who followed Arius's ideas were called "Arians."

Even though Arianism was officially rejected, Arian churches continued to exist for many centuries. They were especially strong in some Germanic kingdoms in Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. Over time, these churches either changed their beliefs or were taken over by other Christian groups.

Contents

Arius's Life

It is hard to know everything about Arius's life and teachings. This is because most of his own writings were destroyed by his opponents. We mostly know about him from what others wrote, especially those who disagreed with his ideas.

Arius's father was named Ammonius. Arius likely studied in Antioch under a teacher named Saint Lucian. Later, in Alexandria, he became a deacon and then a presbyter (a type of priest) in 313 AD.

People who knew Arius, even his opponents, described him as a dedicated and moral person. He was said to be tall, thin, and well-spoken. He was seen as someone with strong beliefs. Some historians even suggest that Arius was quite traditional in his views. He was concerned that Christian ideas were mixing too much with Greek paganism.

Exile and Death

The First Council of Nicaea decided against Arius's teachings. As a result, Arius was sent away from his home (exiled). However, this did not end the debate. Emperor Constantine later allowed Arius to return. Arius had changed some of his ideas to be less offensive to his critics.

In 335 AD, a major opponent of Arius, Athanasius of Alexandria, was exiled. The next year, Arius was welcomed back into the church. Emperor Constantine wanted Arius to be received by the bishop of Constantinople. But the bishop prayed that Arius would die before this could happen.

Arius died in 336 AD. Some modern historians think he might have been poisoned by his enemies. Others at the time believed his death was a miracle, showing that his ideas were wrong. His death, however, did not stop the Arian debate. This debate continued for centuries in different parts of the Christian world.

Arianism After Arius

How Arianism Spread

After Arius's death, his ideas continued to be important. Emperor Constantius II, who followed Constantine, was a supporter of Arianism. During his rule, Arianism became very strong.

Later, Emperor Theodosius I worked to end Arianism among the main groups in the Eastern Roman Empire. He used laws and called another major church meeting in 381 AD. This meeting again condemned Arius's ideas. It also strengthened the Nicene Creed, which stated that Jesus and God the Father were of the same divine essence. This largely ended the influence of Arianism in the Roman Empire's eastern parts.

Arianism in Western Europe

In the Western Empire, Arianism had a different story. A Gothic Christian named Ulfilas became a bishop and helped spread Arianism among the Goths and Vandals. These were powerful Germanic tribes. Because of this, Arianism survived among these groups for a long time. It lasted until the 7th or 8th century, when their kingdoms either fell or they became Nicene Christians. Arians also continued to exist in North Africa, Spain, and parts of Italy for some time.

Arian Ideas Today

Some Christian groups today have beliefs that are similar to Arianism. For example, Jehovah's Witnesses teach that Jesus is a created being and not God himself. Some Christians in the Unitarian Universalist movement also have ideas similar to Arius. They might see Jesus as a special moral leader but not equal to God the Father.

Arius's Main Beliefs

Arius's main teachings were about the relationship between God the Father and Jesus, often called the Logos or Word. Here are some of his key ideas:

- He believed that Jesus (the Word) and God the Father were not of the same divine essence.

- He taught that Jesus was a created being. This means Jesus was made by God, rather than being eternal like God.

- Arius believed that the world was created through Jesus. So, Jesus existed before the world and before all time.

- However, Arius also believed there was a time when Jesus did not exist. He was "begotten" (brought into being) by the Father before anything else.

Arius's Writings

Only a few of Arius's writings still exist today. These include letters he wrote to other church leaders. We also have short parts of his work quoted by his opponents. These quotes are often brief and taken out of context. This makes it hard to know exactly what Arius truly believed.

One of his most famous works was called the Thalia. This was a popular book that mixed prose and poetry. It explained his views on Jesus. Only small pieces of the Thalia survive, mostly quoted by his opponent Athanasius. These fragments give us a glimpse into Arius's ideas, but they do not show his full system of thought.

See Also

In Spanish: Arrio para niños

In Spanish: Arrio para niños

- Anomoeanism

- Arian controversy

- Arianism

- Semi-Arianism

- Nontrinitarianism

- Oneness Pentecostalism

- Unitarianism

- First Council of Nicaea