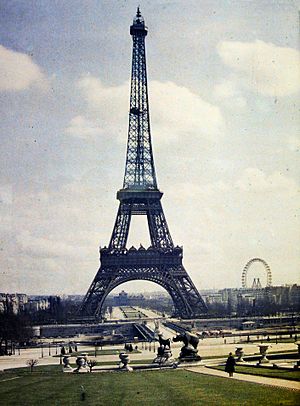

Autochrome Lumière facts for kids

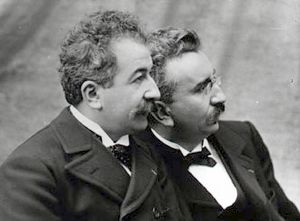

The Autochrome Lumière was an early way to take color photos. It was invented by the Lumière brothers in France. They got a patent for it in 1903 and started selling it in 1907.

Autochrome was the main way to take color pictures for many years. It was popular before newer color films came out in the mid-1930s.

Before the Lumière brothers, a person named Louis Ducos du Hauron found a way to make color images. He used a method that created natural colors by layering things. This idea became the basis for all commercial color photography. The Lumière brothers improved on this method. Autochrome became one of the most used types of color photography in the early 1900s. People liked its unique look.

Contents

How Autochromes Work

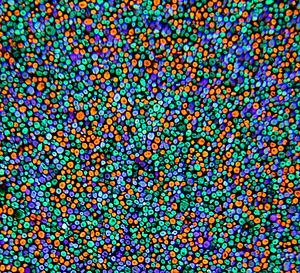

Autochrome uses a special glass plate. This plate has tiny, colored grains of potato starch on one side. These grains are dyed red-orange, green, and blue-violet. They act like tiny color filters. Black filler fills the small spaces between the grains.

On top of this filter layer, there's a black-and-white silver halide emulsion. This emulsion is sensitive to light.

Taking a Photo

When you used an Autochrome plate, you put it in the camera with the clear glass side facing the lens. This meant the light went through the colored filter layer first. Then it hit the light-sensitive emulsion.

A special orange-yellow filter was also needed in the camera. This filter helped block ultraviolet light. It also controlled how much blue and violet light reached the plate.

Autochrome plates needed much longer exposure times than black-and-white plates. This was because a lot of light was lost through the filters. So, you usually needed a tripod to keep the camera still. It was also hard to photograph things that were moving.

After taking the picture, the plate was processed in a special way. This process turned the negative image into a positive transparency. This means you could see the full-color image when light shone through it.

Seeing the Colors

The tiny colored starch grains and the silver image layer stayed perfectly lined up. Each starch grain was exactly over a tiny part of the silver image.

When you looked at the finished image with light shining through it, each silver bit acted like a tiny filter. It let more or less light pass through its matching colored starch grain. This recreated the original colors of the scene. From a normal distance, the light from the individual grains blended together. This made you see the full color picture.

Making Autochrome Plates

To make the Autochrome color filter, a thin glass plate was first covered with a sticky layer. The dyed starch grains were very small, about 5 to 10 micrometers in size. The three colors were mixed together so well that the mixture looked gray.

These grains were then spread onto the sticky layer. They formed a layer that was only one grain thick. There were about 4 million grains per square inch! It's still a bit of a mystery how they avoided big gaps or overlapping grains.

They found that pressing the grains very hard made them flatter and more transparent. This also made them touch each other more, reducing wasted space. Since pressing the whole plate at once was hard, they used a "steamroller" method. This flattened only a small area at a time. Lampblack was used to fill any tiny spaces left.

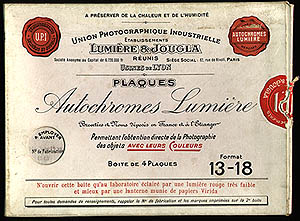

Next, the plate was coated with a protective layer called shellac. This kept the colored grains and dyes safe from the water-based gelatin emulsion. The emulsion was put on after the shellac dried. Finally, the large finished plate was cut into smaller ones. These were packed in boxes of four. Each plate came with a black piece of cardboard to protect the delicate emulsion.

How to View Autochromes

Autochrome images often looked quite dark because of the color screen. So, you needed bright light and special ways to view them to see them well.

Popular Viewing Methods

Stereoscopic Autochromes were very popular. These were two images taken from slightly different angles. When viewed through a stereoscope, they created a 3D effect. People in the early 1900s found this combination of color and depth amazing. These small images were usually viewed in a small, hand-held box called a stereoscope.

Larger Autochrome plates were often shown in a "diascope." This was a folding case with the Autochrome image and a special glass diffuser. There was also a mirror inside. You would place the diascope near a window. Light would shine through the Autochrome, and you would see the bright, colorful image in the mirror.

Slide projectors, then called magic lanterns, were also used. These were great for public shows. But projectors needed a very bright and hot light source. This heat could damage the plate if it was shown for too long. Many old Autochromes have some "tanning" damage from this. Today, projecting these rare images is not recommended.

Modern Viewing

Using a "light box" to view Autochromes is common now. However, this can make the colors look less bright. The many layers on the plate can scatter light, making the image look a bit hazy. Also, artificial light, especially fluorescent light, can change how the colors look. The Lumière Brothers designed Autochromes to be seen in natural daylight.

Making copies of Autochromes with modern film or digital cameras can also cause problems. This is because modern color systems use red, green, and blue. Autochromes use red-orange, green, and blue-violet. This difference can change the colors in the copy.

It's very hard to truly know what an Autochrome image looks like without seeing the original in person. It also needs to be lit correctly.

Autochrome plates can get damaged over time. Each layer can be affected by moisture, air, cracking, or flaking. They can also be damaged by handling. To protect them, they need careful lighting, special materials, and controlled humidity.

Artistic Qualities

If an Autochrome was made well and kept safe, its colors can be very good. The dyed starch grains are a bit coarse. This gives the image a soft, "pointillist" look, like a painting made of tiny dots. Sometimes, faint stray colors can be seen, especially in bright areas like skies. These effects are more noticeable in smaller images.

Autochrome has been called "the color of dreams." This soft, dream-like quality might be why it stayed popular. It was liked even after newer, more realistic color methods became available.

Autochromes were hard to make and quite expensive. But they were fairly easy to use. Many amateur photographers loved them, especially those who could afford them. However, serious "artistic" photographers didn't use them as much. This was because Autochromes were not very flexible. They were hard to show publicly, and it was difficult to change or "manipulate" the photos. This manipulation was popular with artists at the time.

New Film Versions

Autochromes continued to be made as glass plates into the 1930s. Then, film versions came out. Lumière Filmcolor sheet film was released in 1931. Lumicolor roll film followed in 1933.

These new film versions quickly replaced the glass plates. But their success didn't last long. Companies like Kodak and Agfa soon started making their own multi-layer color films. These included Kodachrome and Agfacolor Neu.

Even so, the Lumière products had many loyal fans, especially in France. People kept using them long after modern color films were available. The very last version, Alticolor, came out in 1952 and stopped being made in 1955. This marked the end of the Autochrome's nearly 50-year public life.

Important Autochrome Collections

Between 1909 and 1931, a French banker named Albert Kahn collected 72,000 Autochrome photographs. These photos showed life in 50 countries around the world. This collection is one of the largest of its kind. It is kept at The Albert Kahn Museum (Musée Albert-Kahn) near Paris. A new book of images from this collection was published in 2008.

The National Geographic Society used Autochromes a lot for over twenty years. They still have 15,000 original Autochrome plates in their archives. This collection includes unique photos, like many Autochromes of Paris from 1925 and 1936.

The U.S. Library of Congress has a huge collection of photos by American photographer Arnold Genthe. In 1955, 384 of his Autochrome plates were part of this collection.

The George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York, has a large collection of early color photography. This includes some of the first Autochrome images and materials used by the Lumière brothers.

The Bassetlaw Museum in Retford, England, has over 700 Autochromes by Stephen Pegler. This includes over 100 plates bought by the museum in 2017. The images show many things, like still lifes, people, local places, and his travels. They were taken between 1910 and the early 1930s. Pegler's collection is thought to be the largest by one photographer in Britain.

The Royal Horticultural Society in the UK has some of the earliest color photos of plants and gardens. These were taken by amateur photographer William Van Sommer. They include photos of RHS Garden Wisley from around 1913.

Commercial Use

One of the first books to use color photography used the Autochrome technique. The 12 volumes of "Luther Burbank: His Methods and Discoveries, Their Practical Application" had 1,260 color photos. It also included a chapter explaining how the Autochrome process worked.

In the early 1900s, Ethel Standiford-Mehling was a photographer and artist. She owned the Standiford Studio in Louisville, Kentucky. She was asked to create an Autochrome diascope of two children. Both the Autochrome photo and the diascope viewing device are still well preserved today.

Vladimír Jindřich Bufka was a pioneer who helped make Autochrome popular in Bohemia.

Modern Interest

Some people today are still interested in the Autochrome process. A few groups in France are even working with original Lumière machinery and notes. For example, French photographer Frédéric Mocellin created a series of images in 2008 using this old method.

The British artist Stuart Humphryes has also helped make Autochromes popular again. He enhances Autochrome images for magazines, newspapers, and online. He has many followers on his social media where he shares his work.

Gallery

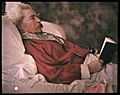

- Autochrome images

-

Family in Paris 1914

-

House in Stockholm, Autochrome, 1930.

-

Autochrome portrait of Mark Twain, 1908.

See Also

- Dufaycolor

- Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky