Aztec warfare facts for kids

Aztec warfare was all about the army, weapons, and how the Aztecs expanded their empire. This included the powerful Aztec Triple Alliance made up of the cities of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan.

The Aztec army had many common people who had basic training. There were also many professional warriors from noble families. These warriors were part of special groups and ranked by their achievements. The Aztec government wanted to grow its power and collect payments from other cities. Warfare was key to their politics. Every Aztec boy learned basic military skills from a young age. Commoners could only move up in society by doing well in war, especially by capturing enemies. Capturing enemies was also a big part of Aztec religious festivals. So, warfare was super important for both the Aztec economy and their religion.

Contents

Why the Aztecs Fought Wars

Aztec warfare had two main goals. First, they wanted to take over enemy cities (Altepetl) to collect tribute and make their empire bigger. Second, they wanted to capture people for religious ceremonies. These goals shaped how the Aztecs fought. Most wars were political, driven by nobles who expected their ruler, the Tlahtoāni, to expand the empire. Common people also hoped to improve their lives through successful warfare.

When a new ruler was chosen, his first job was to lead a military campaign. This showed he was a strong warrior and warned other cities not to rebel. It also provided many captives for his coronation ceremony. If a ruler failed in his first campaign, it was a very bad sign. This happened to Tizoc, who was poisoned by nobles after several failed wars.

What Was a Flower War?

The Aztecs also fought a special kind of war called a flower war (xōchiyāōyōtl). These battles were planned beforehand between armies. They weren't meant to conquer cities directly. Instead, they served several purposes. One main goal was to capture people for religious ceremonies.

Historians like Ross Hassig suggest four main reasons for flower wars:

- They showed off the Aztecs' military strength. The Aztec army was usually bigger, so they could send fewer soldiers than their enemies. Losing a flower war was less damaging for them.

- These wars slowly wore down their enemies. The large Aztec army could fight small battles often. This would tire out opponents until they were ready to be conquered.

- Flower wars let rulers keep fighting at a low level when they were busy with other things.

- Most importantly, they were like propaganda. They showed other cities and the Aztec people how powerful the Aztecs were. They also brought a steady supply of captives to Tenochtitlan.

- The flower war was also a ritual battle to capture victims for sacrifice to their god Xipe Totec.

Becoming an Aztec Warrior

Warriors were very important in Aztec life and culture. When an Aztec boy was born, he received two warrior symbols. A shield was placed in his left hand, and an arrow in his right. After a short ceremony, his umbilical cord, shield, and arrow were buried on a battlefield by a famous warrior. These items symbolized the boy's future as a warrior. Each shield and arrow was made just for him, showing his family and the gods. These rituals show how important warriors were to the Aztecs.

For girls, their umbilical cord was buried under the family fireplace. This showed that their future life would be at home, taking care of the household.

Life Beyond Battles

All boys from age 15 were trained to be warriors. However, the Aztec society didn't have a full-time army. Warriors were called to fight through a Tequital, which was a government order for goods and labor. When not fighting, many warriors were farmers or traders, learning skills from their fathers. Warriors usually married in their early twenties and were a key part of daily Aztec life.

Being a warrior offered a way to move up in Aztec society. If a warrior did well, they received gifts and public recognition. If they reached the rank of Eagle or Jaguar warrior, they became nobles. These high-ranking warriors became full-time soldiers. They protected merchants and the city, acting like a police force.

How Aztec Warriors Looked

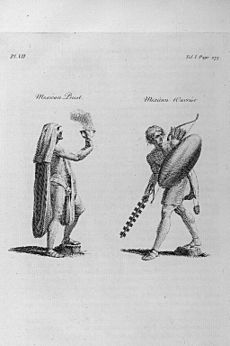

Appearance was very important in Aztec culture. A warrior's clothing showed their success in battle. A warrior's rank depended on how many enemy soldiers they had captured.

- A warrior who captured one person carried a macuahuitl (wooden sword with obsidian blades) and a plain chimalli (shield). They also got a special cape and loincloth.

- A two-captive warrior could wear sandals in battle. They also wore a feathered warrior suit and a cone-shaped cap. These suits are often seen in the Codex Mendoza.

- A four-captive warrior, like an Eagle or Jaguar warrior, wore an actual jaguar skin over their body. Their head would show through the jaguar's mouth.

These high-ranking warriors also had expensive jewelry and weapons. Their hairstyle was unique: hair sat on top of their head, parted into two sections with a red cord. The cord had green, blue, and red feathers. Shields were made of wicker wood and leather, so few have survived today.

Aztec Fortifications

The Aztecs didn't always control their empire tightly. But they did build fortifications in some places. For example, they had strongholds at Oztuma to control rebellious groups. They also built garrisons in Quauhquechollan and Malinalco. These helped them keep an eye on enemies like the Tlaxcalteca and the powerful Tarascan state. The borders with the Tarascans were also guarded and partly fortified.

How the Army Was Organized

The Aztec army had two main groups. Commoners were organized into "wards" called calpōlli, led by tiachcahuan (leaders). Nobles were part of professional warrior societies.

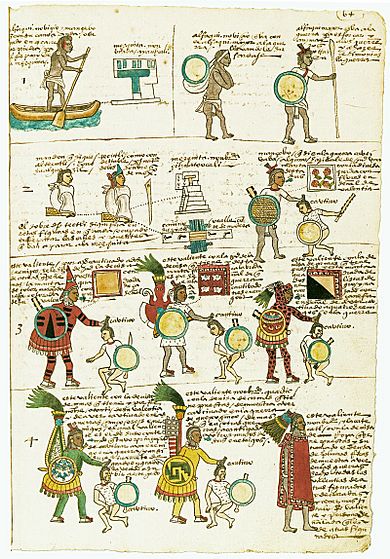

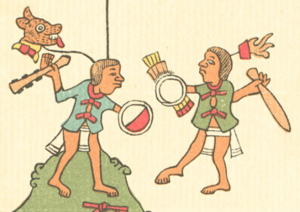

Besides the Tlatoani, the top war leaders were the High General, the Tlacochcalcatl ("The man from the house of darts"), and the General, the Tlācateccatl ("Cutter of men"). These leaders had to name their replacements before battles, in case they died. Priests also joined battles, carrying statues of gods. Boys around age twelve also came along as porters and messengers, mainly for training. The image shows the Tlacateccatl and Tlacochcalcatl and two other officers in their special suits.

Warrior Training

Aztec education prepared young boys to be warriors. The Aztecs had a small standing army. Only elite soldiers, like Jaguar Knights, and those at fortifications were full-time. But almost every boy was trained to be a warrior, except for nobles.

Boys aged 10 to 20 attended one of two schools:

- The Telpochcalli was for commoners. Here, students learned how to fight and became warriors.

- The Calmecac was for nobles. Students here trained to be military leaders, priests, or government officials.

Commoner boys went to the Tēlpochcalli ("house of youth"). At age ten, a section of hair on the back of their head was left long. This showed they hadn't captured an enemy yet. At fifteen, their fathers gave the training responsibility to the telpochcalli. War captains and veteran warriors taught them how to use weapons like shields, swords, bows, and dart throwers (atlatl). Boys were only considered real men after capturing their first enemy warrior.

Noble boys trained at the calmecac ("lineage house"). They received advanced war training from experienced warriors. They also learned about astronomy, calendars, public speaking, poetry, and religion. Calmecac schools were connected to temples. For example, the one in Tenochtitlan was for the god Quetzalcoatl. Noble boys started training younger, some as early as five or six years old.

When formal weapon training began at age fifteen, young nobles joined seasoned warriors in campaigns. This helped them get used to military life and lose their fear of battle. At age twenty, those who wanted to be official warriors went to war. Parents would find veteran warriors to sponsor their sons. The sponsor would teach the youth how to capture enemies. Sons of high-ranking nobles often did better in war because their parents could pay more for better sponsors.

Warrior Ranks

Aztec army ranks were different from modern armies. Warriors had loyalties to many people and groups. Rank wasn't just about their position in the army.

Commoners made up most of the army:

- The lowest were porters (tlamemeh), who carried weapons and supplies.

- Next were the youths from the telpochcalli, led by their sergeants.

- Then came the commoner warriors, yaoquizqueh.

- Finally, commoners who had captured enemies were called tlamanih ("captors").

Above these were the nobles in "warrior societies." Their rank depended on how many captives they had taken. The number of captives decided which special suits of honor (called tlahuiztli) they could wear. It also gave them rights like wearing jewelry, changing hairstyles, wearing warpaint, and getting tattoos. These tlahuiztli became more impressive as warriors moved up, making the best warriors stand out in battle. Higher-ranked warriors were also called "Pipiltin."

Warrior Societies

Commoners who were excellent fighters could become nobles and join some warrior societies, like the Eagles and Jaguars. Noble sons from the Calmecac were expected to join these societies as they advanced. Warriors could move between societies when they became skilled enough. Each society had different clothes, equipment, body paint, and decorations.

Tlamanih

These were warriors who had captured one enemy.

Cuextecatl

These warriors had captured two enemies. They wore red and black tlahuiztli and cone-shaped hats. This rank was created after a war against the Huastec people.

Papalotl

Papalotl (meaning "butterfly") were warriors who had captured three enemies. They wore "butterfly"-like banners on their backs.

Eagle and Jaguar Warriors

Aztec warriors were called cuāuhocēlōtl. This name comes from the Eagle warrior (cuāuhtli) and Jaguar Warrior (ocēlōtl). The bravest and best fighters became either jaguar or eagle warriors. They were the most feared Aztec warriors. Both had special helmets and uniforms. Jaguars wore jaguar skins over their whole body, with their faces showing from the jaguar head. Eagle warriors wore feathered helmets with an open beak.

Otomies

The Otomies (Otōntin) were another warrior society. They were named after the Otomi people, who were known for fierce fighting. It's sometimes hard to tell if "otomitl" means a member of the Aztec warrior society or someone from the Otomi ethnic group who joined the Aztec army. A famous member of this group was Tzilacatzin.

The Shorn Ones

The "Shorn Ones" (Cuachicqueh) were the most respected warrior society. Their heads were shaved except for a long braid over the left ear. Their bald heads and faces were painted half blue and half red or yellow. They were like special forces, taking on tough tasks and helping in battles. To reach this rank, a warrior needed to capture more than six enemies and perform many heroic deeds. They were known for never retreating in battle, even if it meant death from their own comrades.

How the Aztecs Gathered Information

The Aztec empire stayed strong through war or the threat of war. So, gathering information about other cities was crucial before a battle or campaign. It was also important to send messages between military leaders and warriors. This helped them make plans and keep alliances strong. Merchants, ambassadors, messengers, and spies were key to this.

Merchants as Spies

Merchants, called pochteca, were perhaps the most valuable source of information. They traveled throughout the empire and beyond to trade. The king often asked them to bring back general and specific information. This helped the king know what actions to take to prevent invasions or rebellions. As the empire grew, merchants became even more important. Their warnings were priceless, especially for distant areas. If a merchant was killed while trading, it was a reason for war. The Aztecs would quickly and violently strike back, showing how important merchants were.

Merchants were highly respected. When traveling through dangerous areas, Aztec warriors would protect them. In return, merchants spied on enemies while trading in their cities.

Ambassadors and Threats

When the Aztecs decided to conquer a city (Altepetl), they sent an ambassador from Tenochtitlan. This ambassador offered the city protection and explained the benefits of trading with the empire. In return, the Aztecs asked for gold or precious stones for the Emperor. The city had 20 days to decide. If they refused, more ambassadors were sent. These new ambassadors were direct threats. They would explain the destruction the empire could cause if the city said no. They got another 20 days. If they still refused, the Aztec army was sent immediately. There were no more warnings. The cities were destroyed, and their people were taken as prisoners.

Fast Messengers

The Aztecs used a system of runners who were stationed about 4.2 km (2.6 miles) apart along main roads. They relayed messages from the empire to armies or distant cities. For example, runners might tell allies to get ready if a province rebelled. Messengers also warned cities about incoming armies and their food needs. They carried messages between opposing armies and brought news of war outcomes back to Tenochtitlan. The Aztecs developed this system to have impressive communication.

Spies and Disguises

Before a war, special spies called quimichtin (meaning "Mice") went into enemy territory. They gathered useful information for the Aztecs. They noted the land, defenses, and enemy army details. These spies also found people who disagreed with the enemy and paid them for information. The quimichtin traveled only at night. They even spoke the enemy's language and wore their clothes. This job was very dangerous; if caught, they faced torture and their families could be enslaved. Because of this, they were paid very well.

The Aztecs also used trade spies called naualoztomeca. These spies had to travel in disguise. They looked for rare goods and treasures. The naualoztomeca also gathered information at markets and reported it to higher-ranking merchants.

Aztec Warrior Gear

Long-Range Weapons

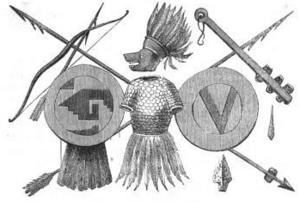

- Ahtlatl: This weapon was like a dart thrower. It launched small darts called "tlacochtli" with more force and from farther away than throwing by hand. It was used by royalty and elite warriors. Warriors on the front lines carried an ahtlatl and a few darts. They would throw them after arrows and sling stones, before fighting hand-to-hand. The ahtlatl could also throw spears.

- Tlacochtli: These were the "darts" launched from an Atlatl. They were like big arrows, about 5.9 feet (1.8 meters) long. They had sharp tips made of obsidian, fish bones, or copper.

- Tlahhuītōlli: The Aztec war bow, made from tepozan wood, about 5 feet (1.5 meters) long. It had a string made from animal sinew. Aztec archers were called Tequihua.

- Mīcomītl: The Aztec arrow quiver, usually made from animal hide. It could hold about twenty arrows.

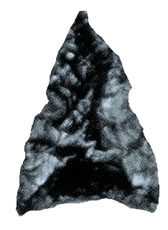

- Yāōmītl: War arrows with barbed obsidian, flint, or bone points. They usually had turkey or duck feathers.

- Tēmātlatl: A sling made from maguey fiber. The Aztecs used oval rocks or clay balls filled with obsidian flakes. A Spanish soldier noted that the stones from Aztec slingers were so strong they could wound armored soldiers.

- Tlacalhuazcuahuitl: A blowgun made of a hollow reed. It used poisoned darts for ammunition. The darts were sharpened wood with cotton fletching, often dipped in poison from tree frogs. This was mainly used for hunting, not war.

Close-Combat Weapons

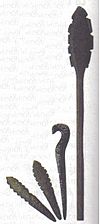

- Mācuahuitl: This was a wooden sword with sharp obsidian blades along its sides. It looked a bit like a modern cricket bat. This was the standard weapon for elite warriors.

- Cuahuitl: A wooden baton made from hardwood, shaped like agave plant leaves.

- Tepoztōpīlli: A wooden spear with a wide head edged with sharp obsidian blades.

- Quauholōlli: A mace-like weapon. Its handle was wood, topped with a wooden, rock, or copper ball.

- Tlāximaltepōztli: An axe similar to a tomahawk. Its head was made of stone, copper, or bronze. One side was sharp, the other blunt.

- Mācuāhuitzōctli: A club about 1.64 feet (50 cm) long, with a knob on each of its four sides and a pointed tip.

- Huitzauhqui: A wooden club, somewhat like a baseball bat. Some designs had flint or obsidian cutting elements on the sides.

- Tecpatl: A dagger with a double-sided blade made of flint or obsidian. It had a fancy stone or wooden handle, about 7 to 9 inches (18 to 23 cm) long. While it could be a side arm, it was mostly used in Aztec sacrifice ceremonies, suggesting warrior priests often used it.

Armor and Protection

- Chīmalli: Shields made from different materials. There were wooden shields ("cuauhchimalli") or maize cane shields ("otlachimalli"). Some were decorative, made with feathers, called māhuizzoh chimalli.

- Ichcahuīpīlli: Quilted cotton armor. It was soaked in salt water and dried in the shade, so salt crystals formed inside. About one or two fingers thick, this armor could resist obsidian swords and atlatl darts.

- Ēhuatl: (meaning "skin") A tunic that some noble warriors wore over their cotton armor or tlahuiztli.

- Tlahuiztli: The distinctively decorated suits of high-ranking warriors. These suits showed a warrior's achievements, rank, and social status. They were usually one piece of clothing, covering the torso and most limbs, offering extra protection. Made with animal hide, leather, and cotton, they made the Ichcahuipilli even more effective.

- Cuacalalatli: The Aztec war helmet, carved from hardwood. They were shaped like animals like howler monkeys, big cats, birds, coyotes, or Aztec gods. These helmets protected most of the head down to the jawline. Warriors saw through the animal's open jaw. They were decorated to match the warrior's tlahuiztli.

- Pāmitl: Identifying emblems worn on the backs of officers and members of important warrior societies. Similar to Japanese sashimono. These banners were often unique to each warrior and helped identify them from a distance. They also helped officers coordinate their units.

Campaigns and Battles

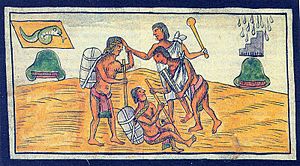

Once war was decided, the news was announced in public places, calling the army to gather for days or weeks. When the troops were ready, and allied cities agreed to join, the march began. Priests usually marched first, carrying statues of gods. The next day, nobles marched, led by the Tlacochcalcatl and Tlacateccatl. On the third day, the main army set out. The Tenochca warriors marched first, followed by warriors from other allied cities. The army marched about 19–32 kilometers (12–20 miles) per day, thanks to their efficient road system.

The size of the Aztec army varied greatly. It could be a few thousand warriors or hundreds of thousands. In one war, the Aztec army had 200,000 warriors and 100,000 porters. Some sources mention armies of up to 700,000 men. In 1506, an Aztec army of 400,000 men conquered Tututepec.

How Battles Were Fought

Battles often started at dawn, sometimes in the middle of the day. Smoke signals were used to show a battle was beginning and to coordinate attacks. The signal to attack was given by drums (Teponaztli) and the conch shell trumpet (quiquiztli).

Battles usually began with projectile fire. Most of the army were commoners armed with bows or slings. Then, warriors moved into close combat. During this phase, the atlatl was used. This weapon was more effective and deadly at shorter distances than slings and bows. The first warriors to fight hand-to-hand were the most distinguished, like the Cuachicque and Otontin. Then came the Eagles and Jaguars, and finally the commoners and young, untrained fighters.

Before close combat, soldiers kept their ranks. The Aztecs tried to surround the enemy. But once hand-to-hand fighting began, ranks broke into individual fights. Young fighters usually weren't allowed to fight until the Aztec victory was certain. Then, they would try to capture prisoners from the fleeing enemy.

It's said that during flower wars, Aztec warriors tried to capture rather than kill their enemies. They sometimes tried to injure opponents to make them unable to fight. Some historians used this to explain why the Aztecs lost to the Spanish. However, this idea has been rejected. Sources show that Aztecs killed Spanish opponents when they could and quickly changed their fighting ways against new enemies.

Other Aztec tactics included faking retreats and setting ambushes. Small groups of Aztecs would attack, then fall back to lure the enemy into a trap where more warriors were hidden. If an enemy retreated into their city, the battle continued there. But usually, the goal was to conquer a city, not destroy it. Once a city was conquered, the main temple was set on fire. This signaled the Aztec victory far and wide. If enemies still refused to surrender, the rest of the city might be burned, but this was rare.

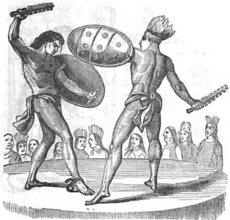

Gladiatorial Combat

Some captives were part of a ritual gladiatorial combat for the god Tonatiuh. A famous warrior named Tlahuicole was one such captive. In this ritual, the captive was tied to a large carved circular stone (temalacatl) and given a fake weapon. The captive had to fight against up to four or seven fully armed jaguar and eagle knights. If the captive survived, they were set free. If they were defeated, they were killed.

What Spanish Eyewitnesses Said

It is one of the most beautiful sights in the world to see them in their battle array because they keep formation wonderfully and are very handsome. Among them are extraordinarily brave men who face death with absolute determination. I saw one of them defend himself courageously against two swift horses, and another against three and four, and when the Spanish horseman could not kill him one of the horsemen in desperation hurled his lance, which the Aztec caught in the air, and fought with him for more than an hour until two-foot soldiers approached and wounded him with two or three arrows.[...] During combat, they sing and dance and sometimes give the wildest shouts and whistles imaginable, especially when they know they have the advantage. Anyone facing them for the first can be terrified by their screams and their ferocity.

Death and Burial

Death was a key part of Aztec culture, from sacrifices to burials. Warriors were especially part of this. When a warrior died in battle or was sacrificed, a ceremony took place. Captured warriors were sacrificed to the sun god. In some cases, the warrior would perform the sacrifice. If a warrior died in battle, his body would be burned on the battlefield. An arrow from the fallen warrior would be brought back, dressed in the Sun god's symbols, and burned.

The Aztecs believed that warriors who died in battle went to the same afterlife place as women who died during childbirth. Mourning for fallen warriors was a long and sacred process. Mourners would not bathe or groom themselves for eighty days. They believed this allowed time for the warrior's soul to reach the Sky of the Sun.

Women had a special role in mourning their dead husbands. They would carry their dead husbands' cloaks wherever they went. They would also let down their hair and dance sadly to the sound of drums. Sons also mourned their dead fathers. They carried a small box with their father's jewelry and earplugs. If an eagle warrior died, they were buried in the eagle warrior hall. They were cremated and placed in the hall with jewelry, jaguar clays, and gold items.

See also

In Spanish: Militarismo mexica para niños

In Spanish: Militarismo mexica para niños

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |