Battle of Meiktila and Mandalay facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Central Burma |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Burma campaign | |||||||

Sherman tanks and trucks of 63rd Motorised Brigade advancing from Nyaungyu to Meiktila, March 1945 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

(Indian National Army) | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,307 killed 15,888 wounded and missing |

6,513 killed 6,299 wounded and missing |

||||||

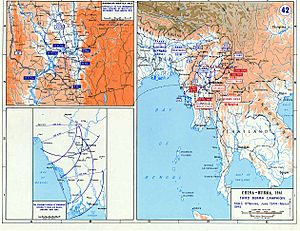

The Battle of Central Burma was a very important fight near the end of World War II in Burma. It included two big battles: the Battle of Meiktila and the Battle of Mandalay. Even though it was hard to get supplies, the Allies used many tanks and vehicles. They also controlled the skies with their planes. Most Japanese forces in Burma were defeated during these battles. This allowed the Allies to take back Rangoon, the capital city, and most of the country with little trouble.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

Japan's Situation in Burma

In 1944, Japan had lost many battles in the mountains between Burma and India. Especially at the Battle of Imphal and Battle of Kohima, the Japanese Fifteenth Army lost many soldiers. Most of these losses were due to sickness and not enough food.

Because of these big losses, Japan changed its military leaders in Burma. On September 1, 1944, Lieutenant General Hyotaro Kimura became the new commander of the Japanese Burma Area Army. Japan was losing the war on many fronts and was saving its resources to defend its home country. Kimura hoped to use Burma's rice fields, factories, and oil to supply his troops there.

Japanese forces in Burma had suffered huge losses in 1944. New soldiers were sent, but many were not in the best shape. Japanese divisions were supposed to have 10,000 soldiers, but most had only half that number. They also did not have enough weapons to fight tanks. To face the many Allied tanks, they had to use their big guns on the front lines. This made it hard to support their foot soldiers.

Japan's air force in Burma, the 5th Air Division, had only a few dozen planes. The Allies had 1,200 planes. Japan's 14th Tank Regiment had only 20 tanks.

Kimura knew his forces could not win against the stronger Allied forces in open areas. So, he planned for the Twenty-Eighth Army to defend the coast. The Thirty-Third Army would fight slowly against American and Chinese forces. These forces were trying to open a land route from India to China. The Fifteenth Army would move back behind the Irrawaddy River. Kimura hoped the Allies would struggle to cross this wide river.

The Allies' Plan

The Allies started planning to take back Burma in June 1944. One idea was to only take back Northern Burma to finish the Ledo Road. This road would connect India and China by land. But this plan was rejected because it only used a small part of their forces. Another idea was to attack Rangoon, the capital city, from the sea. This was also not possible because they did not have enough landing ships.

So, the Allies chose a plan to attack Central Burma. The British Fourteenth Army, led by Lieutenant General William Slim, would lead this attack from the north. This plan was called Operation Extended Capital. Its goal was to capture Mandalay and then chase the Japanese all the way to Rangoon.

To help the Fourteenth Army, the Indian XV Corps would attack the coastal area. This corps also had to capture or build airfields along the coast. These airfields would be used to fly supplies to Slim's troops. The American-led Northern Combat Area Command, mostly made of Chinese troops, would keep moving to meet Chinese armies from China. This would complete the Ledo Road. The Allies hoped these other attacks would keep many Japanese forces busy.

The biggest challenge for the Fourteenth Army was getting supplies. Troops had to be supplied over long, rough roads. Airplanes were very important for bringing supplies to the front lines. On December 16, 1944, 75 American transport planes were suddenly sent to China. This was a big problem for Slim. Even though other planes were quickly brought in, the threat of losing air support was a constant worry.

The Fourteenth Army had strong air support from the RAF. They used bombers, fighters, and fighter-bombers. Heavy bombers were also available. But the most important air support came from transport planes, especially the C47. The Fourteenth Army needed 7,000 flights by transport planes every day during the most intense fighting.

Many of Slim's divisions used both animals and vehicles for transport. This helped them move in difficult areas. But it also made them slow. To fight in the open areas of Central Burma, Slim changed two of his divisions. The Indian 5th Division and Indian 17th Division became partly motorized and partly able to be moved by air.

At this time, there were not many British soldiers available as reinforcements. So, Indian and Gurkha units had to do most of the fighting.

Gathering Information

Both the Allies and the Japanese struggled to know what the other side was planning. They often made wrong guesses.

The Allies had full control of the air. They used planes to scout. They also got reports from special units like V Force and Z Force behind enemy lines. But they did not have the secret information that commanders in Europe had from decoding enemy radio messages. Japanese radio messages were very secure. They used code books and strong ways to hide the messages. Only near the end of the battle, when Japanese communications broke down, did the Allies get important secret information. Also, the Allied armies did not have enough Japanese language experts to translate messages.

On the other hand, the Japanese were almost blind. They had very few planes for scouting. They also got little information from the people of Burma, who were becoming unhappy with Japanese rule. Some Japanese units had their own spy groups. But these spies could not get or report information fast enough for a quick battle with vehicles.

Starting the Battle

As the rainy season ended in late 1944, the Fourteenth Army built two crossings over the Chindwin River. They used special bridges that could be put together quickly. General Slim thought the Japanese would fight in the Shwebo Plain, between the Chindwin and Irrawaddy Rivers. On November 29, the Indian 19th Division started the attack from the northern crossings. On December 4, the Indian 20th Division attacked from the southern crossing.

Both divisions moved forward quickly, with little resistance. The 19th Division was especially fast. It reached Indaw, an important rail center, only five days later. Slim then realized his idea that the Japanese would fight before the Irrawaddy River was wrong. Since only one of his corps' divisions had started fighting, he could change his plan. The 19th Division was moved to another corps. This corps would continue to clear the Shwebo plain and attack Mandalay.

The rest of the IV Corps, with extra divisions, was moved from the army's left side to its right. Its new job was to move down the Gangaw Valley, west of the Chindwin. Then, it would cross the Irrawaddy River near Pakokku. Its main goal was to quickly capture Meiktila, a very important supply and communication center. By taking Meiktila, Slim would cut off all supplies going north towards Mandalay. This would speed up the end of that battle and help take back all of Burma. To trick the Japanese, a fake corps headquarters was set up near Sittaung. All radio messages to the 19th Division were sent through this fake HQ.

To let their main forces retreat across the Irrawaddy, the Japanese left small groups of soldiers in several towns in the Shwebo Plain. In January, the Indian 19th Division and British 2nd Division cleared Shwebo. The Indian 20th Division fought hard to take Monywa, a big river port. Most of the Japanese rearguards were destroyed. The Japanese also held onto some hills near Mandalay.

Meanwhile, IV Corps started moving down the Gangaw Valley. To keep the presence of heavy IV Corps units a secret, the advance of the 7th Indian Infantry Division was hidden by two lighter brigades. When these brigades met Japanese resistance at Pauk, Allied planes bombed the town heavily.

The route IV Corps used needed improvements in many places for heavy vehicles. At one point, the line of vehicles stretched for 350 miles.

Crossing the Irrawaddy River

The 19th Indian Division crossed narrow parts of the Irrawaddy at Thabeikkyin on January 14, 1945, and at Kyaukmyaung the next day. They fought hard for several weeks against attacks by the Japanese 15th Division. Crossing the wider parts of the river downstream needed more planning. The Fourteenth Army did not have many assault boats or ferries, and much of this equipment was old.

Slim planned for the 20th Division and 7th Division to cross at the same time on February 13. This was to keep his main plan a secret. The 20th Division crossed west of Mandalay. They made small footholds, but the Japanese 31st Division attacked them every night for almost two weeks. Allied fighter-bombers destroyed many Japanese tanks and guns. Eventually, the 20th Division made its footholds into one strong area.

In IV Corps' area, it was very important for Slim's plan that the 7th Division quickly captured the area around Pakokku and made a strong foothold. This area was defended by the Japanese 72nd Mixed Brigade and units of the Indian National Army.

The Indian 7th Division's crossing was delayed by 24 hours to fix boats. It was done on a wide front. One brigade made a fake attack to trick the Japanese, while another attacked Pakokku. However, the main attack at Nyaungu and a second crossing at Pagan (an ancient capital with many temples) started badly. Pagan and Nyaungu were defended by two battalions of the Indian National Army. At Nyaungu, British soldiers suffered heavy losses as their boats were hit by machine-gun fire. Finally, tanks and artillery helped suppress the machine guns. This allowed more soldiers to cross and gain a foothold. The next day, the remaining defenders were trapped in tunnels. At Pagan, the crossing also faced heavy machine-gun fire. But then, a boat with a white flag left Pagan. The defenders wanted to surrender, and the Sikhs took Pagan without a fight.

Slim later wrote that this was the longest river crossing against enemy fire in World War II. The Allies did not know that Pagan was the border between two Japanese armies. This delayed the Japanese reaction to the crossing.

Starting on February 17, the 255th Indian Tank Brigade and motorized infantry brigades began crossing into the 7th Division's foothold. To distract the Japanese even more, the British 2nd Division started crossing the Irrawaddy only 10 miles west of Mandalay on February 23. This crossing also almost failed due to leaky boats. But one brigade crossed successfully, and the others followed.

Military Forces Involved

At this point, the Japanese quickly sent more troops to their Central Front. These came from the northern front, where American and Chinese forces had mostly stopped fighting. They also sent reserve units from Southern Burma.

| Japanese Forces | Allied Forces |

|---|---|

|

|

Taking Meiktila

The Indian 17th Division, led by Major General David Tennant Cowan, left the Nyaungu crossing on February 20. They reached Taungtha, halfway to Meiktila, by February 24. This division had two motorized brigades and a tank brigade.

On February 24, Japanese leaders were meeting in Meiktila. They were discussing a possible counter-attack north of the Irrawaddy. The Japanese command was surprised by the Allied attack. An officer reported that 2,000 vehicles were moving on Meiktila. But Japanese staff thought this was a mistake and changed it to 200 vehicles, thinking it was just a small raid. They had also ignored an earlier report of a huge line of vehicles moving down the Gangaw Valley.

On February 26, the Japanese realized how big the threat was. They started preparing Meiktila for defense. The town was between lakes, which made it hard for attackers to spread out. About 4,000 defenders were there. They tried to dig in. The Indian 17th Division captured an airstrip 20 miles northwest at Thabutkon. The air-portable Indian 99th Brigade was flown into this airstrip. Fuel was dropped by parachute for the tank brigade.

Three days later, on February 28, the 17th Division attacked Meiktila from all sides. They had strong artillery and air support. One brigade set up a roadblock southwest of the town to stop Japanese reinforcements. The main part of the brigade attacked from the west. Another brigade attacked from the north. The tank brigade swept around the town to capture the airfields to the east and attack from the southeast.

After the first day, the tanks pulled out of the town at night. The next day, March 1, General Slim and the Corps commander watched anxiously. They worried the Japanese might hold out for weeks. But the town fell in less than four days, despite strong Japanese resistance. The Japanese had many big guns, but they could not focus their fire enough to stop any single attacking brigade. They also lacked weapons to fight tanks. Slim later described how two groups of Gurkha soldiers, supported by one M4 Sherman tank, quickly took over Japanese bunkers with few losses. Some Japanese soldiers tried to destroy tanks by hiding in trenches with bombs. But most were shot by Allied soldiers.

Japanese Attack on Meiktila

The Japanese troops rushing to Meiktila were shocked to find they now had to take the town back. The Japanese forces included parts of the 49th, 18th, and 2nd Divisions, plus other special units.

Many Japanese regiments were already weak from earlier fighting. They had about 12,000 men in total, with 70 guns. The Japanese divisions could not talk to each other. They lacked information about the enemy and even good maps. In Meiktila, the Indian 17th Division had 15,000 men, about 100 tanks, and 70 guns. They would get more reinforcements during the battle.

Even as the Japanese arrived, columns of motorized Indian infantry and tanks left Meiktila. They attacked groups of Japanese troops and tried to clear a land route back to Nyaungu. There was heavy fighting for several villages and strong points. The attempt to clear the roads failed, and the 17th Division pulled back into Meiktila.

The first attacks by the Japanese 18th Division from the north and west failed with heavy losses. From March 12, they attacked the airfields east of the town. The defenders were supplied by planes through these airfields. The 9th Indian Infantry Brigade (from Indian 5th Division) was flown into the airfields starting March 15 to help defend Meiktila. Landings happened under fire, but only two planes were destroyed. The Japanese fought closer to the airfields. From March 18, air landings were stopped. Supplies were dropped by parachute instead.

Meanwhile, on March 12, Kimura ordered Lieutenant General Masaki Honda to take command of the battle for Meiktila. Honda's staff took control on March 18. But without their communication units, they could not properly coordinate the attacking divisions. Attacks remained disorganized. The defenders also kept attacking. They would leave the town every day to attack any Japanese groups in nearby villages. Then they would defend the ground they took before pulling back to the main town. This made it hard for the Japanese to gather enough strength for a successful attack. The Japanese used their big guns on the front line with their foot soldiers. This destroyed some enemy tanks but also led to the loss of many Japanese guns. During a big attack on March 22, the Japanese tried to use a captured British tank, but it was destroyed. The attack was pushed back with heavy losses.

The main goal was achieved: the Japanese forces fighting in the north were cut off from supplies and quickly weakened.

Lieutenant Karamjeet Singh Judge was a brave soldier who fought in this battle. He was given the Victoria Cross (a very high award) after he died for his actions on March 18.

Fighting at Yenangyaung and Myingyan

While Meiktila was under attack, the other main unit of British IV Corps, the Indian 7th Division, was fighting to keep its own crossing point. It also tried to capture the important river port of Myingyan. And it helped another brigade against attacks on the west bank of the Irrawaddy. The Japanese tried to take back the British foothold at Nyaungu. Meanwhile, the 2nd Infantry Regiment of the Indian National Army was ordered to protect the side of Kimura's forces. They also had to keep British forces busy around Nyaungyu and Popa. These forces did not have heavy weapons or artillery. So, they used guerrilla tactics and worked with small Japanese units. They were successful for some time.

The Indian 7th Division now had to reopen the supply routes to the Indian 17th Division, which was trapped in Meiktila. They had to stop their attack on Myingyan. Around mid-March, a motorized brigade from the Indian 5th Division joined them. They started clearing Japanese and Indian National Army troops from their strongholds around Mount Popa. This helped clear the land route to Meiktila.

Once they connected with the defenders of Meiktila, the Indian 7th Division attacked Myingyan again. They captured it after four days of fighting, from March 18 to 22. As soon as it was captured, the port and the Myingyan-Meiktila railway were fixed. They were then used to bring supplies by river.

Mandalay Falls

In late January, the Indian 19th Division cleared the west bank of the Irrawaddy. Then, it moved all its forces to its crossing points on the east bank. By mid-February, the Japanese 15th Division facing them was very weak. General Rees launched an attack southwards in mid-February. By March 7, his leading units could see Mandalay Hill. This hill has many pagodas and temples.

Lieutenant General Seiei Yamamoto, who led the Japanese 15th Division, did not want to defend Mandalay. But he got strict orders from higher up to defend the city to the death. Lieutenant General Kimura was worried about losing face if the city was given up. Also, there were large supply dumps south of the city that the Japanese could not move or leave behind.

A Gurkha battalion stormed Mandalay Hill on the night of March 8. Several Japanese soldiers held out in tunnels and bunkers under the pagodas. They were slowly defeated over the next few days. Most of the buildings were saved.

As Rees's division fought further into the city, they were stopped by the thick walls of Fort Dufferin. This ancient fort was surrounded by a moat. Big guns and bombs dropped from planes did not do much damage to the walls. An attack through a railway tunnel was pushed back. An attempt to break the walls with 2,000-pound bombs made a hole only 15 feet wide. The 19th Division prepared another attack through the sewers on March 21. But before they could attack, the Japanese left the fort, also through the sewers. King Thibaw Min's wooden palace inside the fort burned down during the siege. This was one of many historic buildings destroyed.

Elsewhere, the 20th Indian Division attacked southwards from its crossing point. The Japanese 31st Division facing them was weakened by losses and soldiers sent to other fights. It fell into disarray. A tank regiment and a scouting regiment from the 20th Division drove almost as far south as the Meiktila fighting. Then they turned north to attack the Japanese from behind. The British 2nd Division also broke out of its crossing point and attacked Mandalay from the west. By the end of March, the Japanese Fifteenth Army was broken into small groups trying to move south to regroup.

End of the Battle

On March 28, Lieutenant General Shinichi Tanaka, Kimura's Chief of Staff, met with Honda. Honda's staff told him that their army had destroyed about 50 British and Indian tanks. This was half the number of tanks in Meiktila. But in doing so, the army had lost 2,500 soldiers and 50 guns. They had only 20 big guns left. Tanaka then ordered Honda's army to stop attacking Meiktila. They were to prepare to stop further Allied advances to the south.

It was already too late. The Japanese armies in Central Burma had lost most of their equipment and their fighting spirit. They could not stop the Fourteenth Army from moving closer to Rangoon. Also, after Mandalay was lost, the people of Burma finally turned against the Japanese. Attacks by local fighters and a revolt by the Burma National Army, which the Japanese had created, helped lead to Japan's final defeat.

Images for kids

-

Admiral Mountbatten talks to soldiers in Mandalay, March 1945.