Battle of Plymouth facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Plymouth |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of First Anglo-Dutch War | |||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 36 ships | 45 ships | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 60 killed & 50 wounded | 91 killed | ||||||

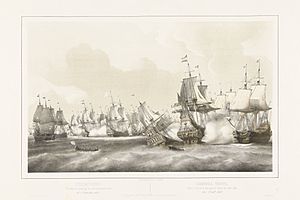

The Battle of Plymouth was a naval battle that happened during the First Anglo-Dutch War. It took place on August 16, 1652, near Plymouth, England. This battle was short, but it ended with a surprising victory for the Dutch over the English.

General George Ayscue of England attacked a group of Dutch ships. These ships were part of a convoy, which is a group of merchant ships traveling together for safety. The Dutch convoy was led by Vice-Commodore Michiel de Ruyter. Interestingly, Ayscue and De Ruyter had been friends before the war started. The Dutch managed to make Ayscue stop fighting. This allowed the Dutch convoy to sail safely into the Atlantic Ocean. Ayscue had to go back to Plymouth to fix his damaged ships.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

In July 1652, Michiel de Ruyter was put in charge of a Dutch fleet. His main job was to protect a large group of merchant ships. These ships were carrying valuable goods. De Ruyter knew that an English fleet, led by Ayscue, was also at sea. Ayscue's goal was to stop and capture the Dutch merchant ships.

De Ruyter's fleet had 23 warships and six fireships. Fireships were old ships filled with flammable materials. They were used to set enemy ships on fire. De Ruyter's ships were not in the best shape. Many of his crews were not well trained. He also had only two months of supplies. Despite these problems, De Ruyter wanted to fight Ayscue's fleet before the merchant ships arrived. This way, he would not have to worry about protecting them during the battle.

De Ruyter sailed into the English Channel. He soon realized that Ayscue was trying to avoid a fight with his warships. Ayscue wanted to sneak past De Ruyter and attack the convoy instead. De Ruyter tried to get Ayscue's attention by sailing near the English coast. This caused some alarm among the local people. Even though Ayscue's fleet grew to 42 ships, he still did not attack.

During this time, De Ruyter lost two of his ships. They crashed into each other while escorting a single merchant ship. One ship, the Sint Nicolaes, sank. The other, Gelderlandt, was badly damaged.

On August 11, De Ruyter finally met up with the convoy. It had 60 merchant ships. The convoy also brought ten more warships, which increased De Ruyter's total to 31 warships. His orders were to escort the convoy safely to the Atlantic. Most of the merchant ships would then go to the Mediterranean Sea. De Ruyter's original squadron would wait for ships coming from the West Indies. Ayscue's fleet had grown even larger, to 47 vessels. This included 38 warships and five fireships.

The Battle Begins

On August 15, the English fleet spotted the Dutch ships near Plymouth. The next day, around 1:30 PM, Ayscue launched a direct attack. He tried to hit the convoy first, hoping to scatter the merchant ships and capture them. However, De Ruyter did something unexpected. He quickly moved his warships to block Ayscue's attack. This protected the valuable merchant ships.

Ayscue's ships generally had bigger guns. But his fleet was very disorganized. His fastest ships, including his own flagship George, had rushed ahead. They hoped to catch slow Dutch merchant ships. Because of this, they could not form a proper battle line. This meant they could not use their powerful guns effectively.

The Dutch squadron, however, was in a good defensive line. They were sailing to the northwest. The battle started when the Dutch fleet met seven English ships. Both sides claimed to have "broken the enemy line." This means they sailed through the enemy's formation. After this first clash, the Dutch gained an advantage. They turned their ships and attacked again from the north. The battle quickly became a confusing mess. The best English ships were surrounded by many Dutch vessels. The slower English ships, many of which were hired merchant ships with untrained crews, did not want to join the intense fighting. So, the English advantage in numbers did not help them much.

A Heroic Stand

One of the largest Dutch ships was the Vogelstruys. It was a Dutch East India Company warship with powerful 18-pounder guns. This ship got separated from the rest of the Dutch fleet. Three English ships attacked it at once and tried to board it. The crew of the Vogelstruys was almost ready to give up. But their captain, Douwe Aukes, threatened to blow up the ship rather than surrender. This made the crew fight even harder. They pushed back the English boarding teams. The English ships were badly damaged, and two were even sinking. They had to stop their attack.

The Dutch used a special tactic. They fired chain shot at enemy ships' masts and sails. Chain shot was two cannonballs connected by a chain. This would damage the rigging and make the enemy ships unable to move. By the end of the afternoon, Ayscue felt he was not getting enough support from his own fleet. He decided to stop the battle. He retreated to Plymouth to repair his ships. He did not want any of his ships to be captured. One English ship, the Bonaventure, only escaped because an English fireship set itself on fire. This scared off the attacking Dutch ships.

De Ruyter wrote in his journal: "If our fireships had been with us... we would with the help of God have routed the enemy; but praised be God who has blessed us in that our enemy fled by himself, though 45 sails strong and of great force."

Neither side lost a warship in the battle. However, many sailors were killed or wounded. The Dutch had about 60 dead and 50 wounded. English losses are reported differently. One report said as many as 700 casualties, including wounded. Another said 91 dead. This included Ayscue's flag captain, Thomas Lisle. Rear-Admiral Michael Pack had his leg removed and died soon after. The English also lost one fireship.

After the Battle

De Ruyter chased the English fleet after they retreated. The next morning, both fleets were still close to each other. De Ruyter hoped to capture some straggling English ships. Several English ships were being towed because they were so damaged. However, Ayscue did not want to lose his good name. On August 17, he convinced his officers to fight again if needed. He managed to get his entire fleet safely back to Plymouth by August 18.

De Ruyter then sent two warships to help the merchant fleet through the Channel. He thought about attacking the English fleet while it was in Plymouth. But he decided against it because he did not have the advantage of the wind. Then he heard that another English admiral, Robert Blake, was sailing towards him with a much larger fleet of 72 ships. De Ruyter chose to move west along the French coast. He spent September gathering more incoming ships from the West Indies.

On September 15, Blake sent a group of 18 ships to stop De Ruyter. But De Ruyter escaped by sailing east along the French coast. Blake's fleet was forced to find shelter from a storm. De Ruyter safely escorted twelve merchant ships to Calais by September 22. By this time, his supplies were almost gone. Soon after, nine or ten of the Dutch ships, including De Ruyter's flagship, had to return to port for repairs. This was likely due to damage from the battle that had not been fully fixed.

A New Hero Emerges

The English ships had expected to easily beat the Dutch. They had more ships and bigger guns. So, their failure to win was a big surprise. For the Dutch people, however, this battle was a great success. They celebrated De Ruyter, who was not very well known before. He became a national hero.

The English blamed some of their merchant ship captains for being cowards. Ayscue was criticized for his poor leadership. He tried to say the battle was a victory, but no one believed him. He lost his command after this battle. This was probably because he had supported the royal family, which was out of favor at the time. Also, he was more interested in capturing valuable merchant ships than fighting a full naval battle. In the early part of the war, many English captains saw the conflict as a way to get rich by capturing Dutch ships. It was only later that they truly tried to control the seas.

This battle was very important for De Ruyter's career. It was the first time he commanded a fleet on his own. Before this, he had only led smaller groups of ships. Because of his success in this battle, he earned the nickname The Sea Lion. Before he could return home, De Ruyter was involved in another battle, the Battle of the Kentish Knock. When he finally arrived in Middelburg, he was honored with a golden chain. This was a reward for his "masculine courage" in the Battle of Plymouth and his "courageous prudence" in the later battle.

Ships Involved

A complete list of all ships involved in the battle does not exist. The English list is not very well known. Below are the lists of ships that are known to have participated. The Dutch list includes the original 23 warships and six fireships that De Ruyter sailed with.

United Provinces

| Ship name | Commander | Guns | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vogelstruys | Douwe Aukes | 40 | VOC-ship (Dutch East India Company) |

| Vrede | Pieter Salomonszoon | 40 | VOC-ship |

| Haes in't Veldt | Leendert den Haen | 30 | Zealand directory ship |

| Sint Nicolaes | Andries van den Boeckhorst | 23 | Frisian admiralty; sank in earlier Somme collision |

| Liefde | Joost Banckert de Jonge | 26 | Zealand admiralty |

| Kleine Neptunis | Michiel de Ruyter | 28 | Z; flagcaptain Jan Pauwelszoon |

| Albertina | Rombout van der Parre | 24 | F |

| Sint Pieter | Jan Janszoon van der Valck | 28 | Admiralty of the Maze |

| Westergo | Joris Pieterszoon van den Broecke | 28 | F; second in command |

| Engel Michiel | Emmanuel Zalingen | 40 | Admiralty of Amsterdam |

| Drie Coningen | Lucas Albertszoon | 38 | A |

| Gelderland | Cornelis van Velsen | 28 | M; damaged in Somme collision |

| Graaf Hendrik | Jan Renderszoon Wagenaer | 30 | F |

| Wapen van Swieten | Jacob Sichelszoon | 28 | Z |

| Kasteel van Medemblick | Gabriel Antheunissen | 26 | Admiralty of the Northern Quarter |

| Westcapelle | Cleas Janszoon Sanger | 26 | Z |

| Eendraght | Andries Fortuijn | 24 | M |

| Amsterdam | Simon van der Aeck | 36 | A |

| Faeme | Cornelis Loncke | 36 | Z |

| Schaepherder | Albert Pieterszoon Quaboer | 28 | F |

| Sarah | Hans Karelszoon Becke | 24 | F |

| Hector van Troye | Reinier Sekema | 24 | F |

| Rotterdam | Jan Arentsen Verhaeff | 26 | M; third in command |

| Hoop | Thomas Janszoon Dijck | A; fireship | |

| Amsterdam | Jan Overbeecke | fireship | |

| Gekroonde Liefde | Jacob Herman Visser | Z; fireship | |

| Orangieboom | Leendert Arendszoon de Jager | A; fireship | |

| Sinte Maria | Jan Cleaszoon Corff | A; fireship | |

| Goude Saele | Cornelis Beecke | A; fireship |

England (George Ayscue)

- George 52 (flagship)

- Amity 36 (Rear-Admiral Michael Pack)

- Success 30 (merchant ship)

- Ruth 30 (merchant ship)

- Brazil frigate 24 (merchant ship)

- Malaga Merchant 30 (merchant ship)

- Increase 36 (merchant ship, Thomas Varvell)

- Vanguard 46 (Vice-Admiral William Haddock)

- Success 36 (William Kendall)

- Pelican 42 (Joseph Jordan)

- Pearl* 24 (Roger Cuttance)

- John and Elizabeth* 26 (merchant ship)

- George Bonaventure* 20 (merchant ship, John Crampe)

- Anthony Bonaventure 36 (merchant ship, Walter Hoxon)

- Unity (merchant ship)

- Maidenhead 36 (merchant ship)

- Constant Anne (ketch - small boat)

- Bachelor (ketch)

- Charity (fireship, Simon Orton) – Used up in battle

Ships marked * are likely to have been there.

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |