Battle of Warsaw (1831) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Warsaw |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the November Uprising | |||||||||

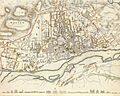

Russian assault on Warsaw in 1831, George Benedikt Wunder |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 77,000 to 78,500 390 cannon |

34,900 to 42,000 205 cannon |

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 9,760–10,600 killed and wounded or 28,000 including wounded and died of wounds 4,000 missing 1 |

9,000–10,800 killed, wounded, and captured 16,000 including deserters after the battle 132 guns 5,000 rifles 1 |

||||||||

The Battle of Warsaw was a major fight in September 1831 between Imperial Russia and Poland. It is also known as the Battle and Storming of Warsaw. After two days of attacks on the city's western defenses, the Polish forces had to give up. The city was then taken over by the Russians. This battle was the biggest and final event of the November Uprising, a war between Poland and Russia from 1830 to 1831.

After nearly a year of fighting, a large Russian army crossed the Vistula River and surrounded Warsaw on August 20. Even though the Poles managed to open a path for supplies, a strong Russian force stayed near the city. The Russian commander, Ivan Paskevich, hoped the Poles would surrender. He knew the Polish leader, Jan Krukowiecki, wanted to talk peace with the Russian tsar, Nicholas I.

However, a group in Warsaw that wanted to keep fighting gained power. They refused the Russian offer to surrender. So, Paskevich ordered his army to attack Warsaw's western defenses. The attack began on September 6, 1831. The Russians surprised the Poles by attacking their strongest position in the area called Wola.

Despite brave defense, especially at Fort 54 and Fort 56, the outer Polish defenses were broken on the first day. At the Wola redoubt, only 11 Polish defenders survived out of 3,500. Fighting continued the next day. Russian cannons were close enough to hit the city itself. Both sides had similar losses. But Polish leaders decided not to risk another terrible event like the Massacre of Praga in 1794. They ordered the city to be left.

On September 8, 1831, Warsaw was in Russian hands. The rest of the Polish Army went to Modlin. The November Uprising ended soon after. Polish soldiers crossed into Prussia and Austria to avoid being captured. The fight for Warsaw became a famous part of Polish culture. Poets like Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Słowacki wrote about it. It also inspired Chopin's Revolutionary Étude. The fall of Warsaw made many people around the world feel sympathy for Poland's struggle for freedom.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

In 1830, many revolutions happened across Europe. These included the July Revolution in France and the Belgian Revolution. These events threatened the political order set up at the Congress of Vienna. The Russian tsars strongly supported this old order. So, the uprising in Poland, where the Polish parliament (Sejm) removed the tsar as king of Poland in January 1831, was a big problem for Russia.

Russia could not send its armies to other parts of Europe until the Polish rebellion was stopped. Because of this, capturing Warsaw was Russia's main goal from the very start of the war.

During the uprising, the Russian army tried to capture Warsaw twice before. In February 1831, forces led by Field Marshal Hans Karl von Diebitsch attacked the eastern suburb of Praga. After a bloody battle at Grochów, the Polish Army successfully retreated to Warsaw. The capital stayed in Polish hands.

Since a direct attack failed, von Diebitsch planned to go around Warsaw and enter from the west. He sent his forces up the Vistula River. Russian divisions were supposed to cross the river and then head north towards Warsaw. But Polish defenses stopped this plan in three battles: Wawer, Dębe Wielkie, and Iganie. The Russians pulled back towards Siedlce, where von Diebitsch got sick and died.

The new Russian commander, Count Ivan Paskevich, decided to wait. He wanted other Polish forces to be defeated first before he marched on Warsaw again. In June 1831, General Antoni Giełgud's attack on Wilno failed. His army had to cross into Prussia to avoid being completely destroyed. Only a small group under General Henryk Dembiński managed to rejoin the main Polish army. This secured Paskevich's northern side.

Paskevich then made a new plan. Instead of attacking Warsaw directly, he would surround it. He wanted to cut off the city from other Polish areas and force it to surrender. Between July 17 and 21, 1831, he crossed the Vistula with his main army. He moved towards Warsaw through Gąbin and Łowicz. Other Russian forces also moved towards the city. General Gregor von Rosen's army (12,000 men and 34 cannons) reached Praga on August 10. General Theodor von Rüdiger's army (12,000 men and 42 cannons) crossed the Vistula and captured Radom.

The new Polish Commander-in-Chief, Jan Zygmunt Skrzynecki, also didn't want a major battle. He ordered Warsaw to be fortified. He let the Russians cross the Vistula without a fight. He believed the war could only be won through diplomacy, with help from the United Kingdom, Austria, and France. If that failed, Skrzynecki thought Warsaw could hold out for weeks. The main Polish Army would then be ready for a decisive battle. On August 10, 1831, Skrzynecki had to resign. Henryk Dembiński, the military governor of Warsaw, replaced him.

Preparing for Battle

Warsaw's Defenses

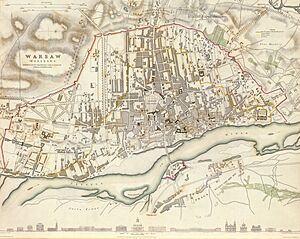

Warsaw grew quickly in the late 1700s and early 1800s. But Poland was in a time of war, so it lacked strong, permanent forts. To make up for this, three lines of earthworks, walls, and palisades were built on both sides of the Vistula. These earthworks were usually several meters high. They were made of sand and clay, reinforced with gabions (baskets filled with earth). They also had a dry moat, a wooden fence, and hidden pits with sharp stakes.

The innermost line of defense followed the old Lubomirski Ramparts. This was a continuous line of earthworks about 3 meters (10 feet) high. It was strengthened by many forts and fortified buildings.

The second line of defenses had forts about 400 to 600 meters (1,300 to 2,000 feet) in front of the inner line. The strongest forts were along the road to Kalisz.

The first, outermost line had smaller forts and walls. It ran in a half-circle from Szopy, through Rakowiec, Wola, and Parysów to the Vistula. These outer forts were 1.5 to 3 kilometers (1 to 2 miles) in front of the third line. Their purpose was to stop the first attacks and break up the Russian army. There were five main groups of earthworks in this outer line:

- Królikarnia (Forts 44 and 45)

- Rakowiec (Forts 48 to 53)

- Wola (Fort 56)

- Parysów (Forts 61 and 62)

- Marymont Forest (Fort 66)

Smaller forts filled the gaps between these large fortifications. The strongest fort in the outer line was Fort 56 in Wola. It was built around the St Lawrence's Church. It was supported by Lunette 57 in front and two forts (54 and 55) to its south. The main headquarters was in Fort 73.

Polish leaders decided to defend the outer line of defenses. This was because 53% of Warsaw's buildings were made of wood. A fire could easily destroy the city. If the enemy broke through all three lines, the city center was also prepared. It had 30 barricades, holes cut in walls for shooting, and mines hidden under major streets.

Armies Ready for Battle

Russian Army

By August 20, 1831, Warsaw was almost completely surrounded by the Russians. Count Paskevich had a very strong army. His main force had between 54,000 and 55,000 soldiers. They were supported by 324 cannons. Another 7,000 soldiers and 20 cannons guarded the river crossings.

By September 5, 1831, the main Russian force grew to 78,500 men. This included 2,000 engineers, 54,000 infantry (foot soldiers), and 17,200 cavalry (horse soldiers). The Russian artillery was much larger than the Polish. It had 382 cannons and 8 mortars, operated by 7,300 men.

The Russian army was stronger, but it had big supply problems. Paskevich's army was too large to feed only from captured lands. It relied on food brought from Russia or from Prussia, which was supposed to be neutral. But a cholera epidemic, brought by Russian soldiers, forced Prussia to close its borders to Russian supplies. To avoid his army starving, Paskevich ordered two permanent bridges built across the Vistula. Only one was finished by the start of the attack on Warsaw.

Polish Army

In early September 1831, the Polish Army had about 62,000 men. The soldiers defending Warsaw numbered 31,100 infantry and 3,800 cavalry. The artillery had 228 cannons and 21 rocket batteries. These were operated by 4,554 regular soldiers and 200 National Guard members.

The number of defenders was not enough to man all the defenses. Some forts had to be left empty. Engineers had estimated that Warsaw's forts needed at least 60,000 troops to be fully defended. There were 15,000 able-bodied members of the Security Guard, the National Guard, and the Jewish City Guard who wanted to fight. But the army refused to give them weapons. They feared losing control over these untrained groups.

The city had over 175,000 civilians and refugees. The defenders were running low on food. However, ammunition supplies were excellent. They had enough for "not one, but three major battles." The Warsaw Arsenal alone held 3 million rounds of ammunition and 60,000 cannonballs.

A cholera epidemic hit Warsaw between May 16 and August 20. 4,734 people got sick, and 2,524 died. On August 15, a riot broke out in the city. Up to 3,000 civilians and soldiers killed suspected spies and traitors. Between 36 and 60 people died. Order was restored, but the situation in the besieged city remained tense.

Training and Morale

Both armies were trained similarly and used similar weapons. The main rifle was the Model 1808 flintlock musket. Its effective range was about 250 meters (820 feet). Some Polish units still used hunting rifles or war scythes. However, the scythe-wielding kosynierzy were only a small part of the Polish forces. Both sides used mostly 6-pounder and 12-pounder cannons.

The Polish Army was mostly made of volunteers. It was organized like Napoleon Bonaparte's army. This meant there was no corporal punishment, and soldiers were highly motivated. But the good morale from the first months of the uprising was gone by September. Many defeats, partial victories, and retreats, along with changing commanders, lowered the soldiers' spirits. Most generals in Warsaw did not fully believe in the uprising's goals. They just wanted to do their job, hoping things would return to normal.

In contrast, the Russian forces had very high morale. Russian commanders had a lot of experience in siege operations. Paskevich himself had captured at least six fortified cities in his career.

The Battle Begins

First Clashes

Facing supply problems, the new Polish Commander-in-Chief, Jan Krukowiecki, ordered an attack on the right bank of the river. Krukowiecki was a conservative. He believed the uprising's main goal was to return to the way things were before the war. He wanted the Russian tsars to be kings of Poland again, but respecting the Polish constitution. He thought foreign help was unlikely. He wanted to force the Russians back to peace talks by defeating them or breaking the siege.

Forces under Girolamo Ramorino and Tomasz Łubieński left the city between August 16 and 20, 1831. They were to bother Russian forces, capture river crossings, bring supplies to Warsaw, and force Paskevich to send some of his troops to fight them. Tomasz Łubieński's army broke the siege and brought much-needed supplies to Warsaw. His forces also cut off the northern supply line for Paskevich's army. Girolamo Ramorino's army defeated von Rosen's forces in several battles.

However, Ramorino did not follow orders. He allowed the defeated Russians to escape. A large part of the Polish forces, experienced soldiers with high morale, wandered aimlessly. They were only a few days' march from Warsaw. Instead of helping Warsaw, Ramorino waited for a week. Then he headed south, away from the enemy.

On September 4, Paskevich sent a message to Warsaw. He asked for surrender and promised to change the constitution. Only three out of ten members of the Polish Diplomatic Commission voted for more talks. On September 5, the Russians were told that the Poles still demanded all lands taken by Russia be returned. They also insisted that Nicholas I was no longer the king of Poland.

On the night before the battle, the Russian Army moved closer to Polish positions. The Guards moved towards Opacze Wielkie. Other units moved to the road to Kalisz and to Włochy. An infantry division occupied the fields between Okęcie and Rakowiec. Other cavalry moved to Zbarż. To complete the encirclement, the 2nd Light Division took positions near Służew. Supply trains and reserves were left in Nadarzyn.

Battle Plans

Paskevich initially did not want a full assault on the city. But the actions of Ramorino and Łubieński forced his hand. His army was low on food and supplies. By early September, the main Russian force had only 5 days' worth of food. On August 28, Paskevich agreed to prepare for a general attack. After arguments among Russian generals, they decided on September 4 to attack the strongest Polish positions in Wola. The attack would focus on Fort 56 and nearby forts.

The Russian I Infantry Corps would storm Fort 57 and move towards Forts 56 and 58. The II Infantry Corps would attack Forts 54 and 55. Other parts of the front would only have small attacks to distract the Poles. Paskevich probably did not want to enter Warsaw. He hoped the Poles would leave or surrender once their outer defenses were broken.

The Polish plan was to defend the front line firmly. Forces under Umiński and Dembiński would be behind the second line of defenses. They would act as a mobile reserve, with artillery and cavalry. Umiński's Corps would cover the southern front. Dembiński's forces would defend the western and northern front. Most Polish forces were in the south. Polish leaders wrongly thought the Russians would attack the weakest part of their defenses, around Królikarnia.

September 6: The First Day

On the western front, Paskevich had a huge numerical advantage. The first Russian line facing Wola had 30,200 soldiers, 144 cannons, and eight mortars. The second line had 39,200 soldiers and 196 cannons. Facing them were 5,300 Polish infantry, 65 cannons, and 1,100 cavalry under Dembiński. Another 4,800 Polish soldiers were in reserve.

At 2:00 AM, Polish lookouts spotted enemy movements and sounded the alarm. The attack began around 4:00 AM. Within an hour, Polish forts 54 and 57 fired on the approaching Russians. Around 5:00 AM, 86 Russian cannons began shelling Polish positions in Wola from 600 meters (2,000 feet) away. The battle had begun.

Fort 56 had three parts, each with its own earthwork, fences, and moat. The central part was also protected by the St. Laurence's Church and its monastery. General Józef Sowiński commanded the fort. It had 1,200 men, 40 engineers, 13 cannons, and two rocket launchers. Fort 57, in front of it, had 300 men and four cannons. To the north was Fort 59, and to the south Fort 54. Other Wola forts were left with few defenders. The most important Polish positions were severely understaffed.

Further south, near Rakowiec, were other forts. The Poles had already left them in early September. Russian infantry captured them without a fight. Forces under General von Strandmann captured Szopy and attacked forts 44, 45, and Królikarnia. Soon, thick smoke covered the battlefield. Polish commanders couldn't tell where the main Russian attacks were coming from. They thought the main attack would be at Królikarnia.

General Dembiński, who commanded the western sector, was the first to realize the mistake. He asked for more troops, but General Krukowiecki refused. Dembiński had to fight alone. He did not send his main reserve to the front line. Instead, he sent only a small force to Fort 58. To make things worse, General Umiński, in the southern sector, focused only on Królikarnia. He did not notice what was happening in Wola. Around 7:00 AM, he sent almost 2,800 men and three cannons to Królikarnia. Forts 54 and 55 received no help.

The Fight for Fort 54

Russian artillery began destroying the outer defenses around Wola. From 6:00 AM, 108 Russian cannons focused on forts 54, 55, and 57. Fort 54 held out, and Polish losses were low. But the cannons of the isolated forts had to hide behind the walls. Forts 59 and 61 could not help their neighbors.

Out of 32 cannons Dembiński had in reserve, only four moved to Fort 58. Around 6:30 AM, nine more cannons joined the fight around Wola. But their help was too little, too late. At that time, two large Russian attack groups formed. The first, under General Nikolai Sulima, attacked Fort 54. The second, under General Friedrich Caspar von Geismar, headed for Fort 55. When von Geismar saw Fort 55 was empty, he sent his 1,500 men to help attack Fort 54. Despite heavy losses, Russian soldiers reached the fence around the earthworks. They began clearing obstacles.

Because of the smoke, Polish commanders in the second line couldn't see the Russians. They did not open fire. The second line did not send help to the first. This was especially bad for Forts 54 and 56. They had to fight alone, without help from Forts 21, 22, and 23 behind them. The most important positions in Wola received only small reinforcements. They were forced to fight alone.

The Polish defenders of Fort 54 fired constantly. But Russian cannons now had a clear shot at the top of the wall. For some reason, the Poles did not use grenades prepared for close combat. When the wall was breached, two Russian regiments charged in. Other Russian soldiers stormed the earthwork itself. After several shots, Polish infantry retreated inside the fort. They fired at Russian soldiers appearing on top of the wall. The first to cross the obstacles was Pavel Liprandi with his men. With 10 times more Russians, the bayonet fight was short. Between 60 and 80 surviving Poles were captured in minutes. Soon after, the gunpowder storage caught fire and exploded. Over 100 Russians died, including their commander. This explosion was made famous in Adam Mickiewicz's poem Reduta Ordona (Ordon's Redoubt). In total, the Russians lost 500 to 600 men attacking Fort 54. The dead were buried in a mass grave.

Expecting a Polish counter-attack, Russian engineers began repairing Forts 54 and 55. At first, only Polish cannons from forts 73, 21, 22, and 23 fired back. Dembiński's reserves did nothing. Seeing no Polish activity, Russian cannons began supporting their neighbors. Russian cannons suffered some losses, but their superiority was clear. Russian batteries moved within 300 meters (980 feet) of Fort 57. This forced the Polish cannons to be removed from the fort. Around 8:00 AM, two Russian groups attacked Fort 57. They hoped a three-hour cannon attack had destroyed the obstacles. But the fence was almost untouched. Russian forces suffered heavy losses from Polish rifle fire and cannons. Officers ordered a retreat, but soldiers kept attacking. Several attacks were stopped with heavy Russian losses. Despite losses, Russian infantry entered the fort and captured it in close combat. Only about 80 Poles were captured. Four managed to escape with their wounded commander. The rest fought and died. Since the captured fort was within range of Polish cannons, the Russians pulled back and hid behind it.

The Fight for Fort 56

Even though forts 54, 55, and 57 were lost, Krukowiecki still thought the attack on Wola was a distraction. He refused to send General Dembiński more troops. Only General Ludwik Bogusławski sent one battalion (about 500 men) to Fort 56 as reinforcements. This battalion was led by Col. Piotr Wysocki, the officer who started the November Uprising. Dembiński abandoned Fort 58. Its cannons, along with 12 others and six rocket launchers from his reserves, were moved between the first and second lines of defense. Around 9:00 AM, General Józef Bem arrived in Wola with 12 cannons. He placed them near the lost Fort 54, on the side of the Russian infantry and cannons shelling Fort 56. Eight more cannons and four rocket launchers arrived to the north of Wola. They joined the defense of Fort 58.

At that time, Russian cannons focused their fire on Forts 56, 59, and 23. This time, the Poles won the cannon duel. Despite more Russian cannons, the Russian artillery suffered losses and had to pull back. Infantry also pulled back behind the captured earthworks. Dembiński did not use this success, and the Polish infantry stayed hidden.

Seeing no Polish activity, the Russian commander ordered all his cannons to fire on Józef Bem's 14 cannons. Under heavy fire, Polish artillery held out for over half an hour. Then they moved to new positions. They continued firing on the Russian army. The cannon duel continued, but the situation at Fort 56 became critical. Shelled from three sides, the largest Polish fort was now alone. With reinforcements, the fort had about 1,660 infantrymen and ten cannons. By 10:00 AM, most artillerymen were killed or wounded. Untrained infantrymen had to replace them, which made the Polish cannons fire slower and less accurately. All the walls were damaged. There was a 30-meter (98-foot) gap in one side.

Paskevich watched the cannon duel from Fort 55. He became sure that the Poles would not help Fort 56. He ordered Russian infantry to attack Fort 56 around 10:00 AM. The attack was made by 13 infantry battalions (about 6,900 men). The Russian forces stormed the obstacles and crossed the fence. But Polish defenders met them with rifle fire from inside the fort, and the attack was stopped. The Russians quickly ordered their second line (2,300 men) to advance. These new forces were pushed back twice into the moat by Maj. Franciszek Biernacki. But in the end, the Polish defenders were overwhelmed. They had to retreat further into the fort. The Russians followed, but their groups lost order. This allowed the smaller Polish force to hold out inside the fort.

Russian forces attacked the central part of Fort 56. Here, the obstacles were still intact. 200 Polish soldiers stopped three attacks by a famous Russian Guards Regiment. The Russians lost two commanders before reaching the moat. When 2,900 Russians reached the top of the wall, they were surprised by a second wall behind it. Russian infantry retreated and hid under the first wall. Biernacki, fighting in the northern part, managed to push out the Russian infantry. But he was killed during the counter-attack. The Poles pulled back into the trees on the far side of the fort. To fix the situation, General Sowiński ordered a company to join the fight in the north. The new commander, Maj. Lipski, organized another counter-attack. He led his men in a charge and pushed the Russians back again. But the Russians kept control of the wall to the north-west. A short standoff followed. Polish infantry and their single cannon prevented much larger enemy forces from entering the fort.

Seeing their forces fail, Paskevich and Pahlen decided to send even more troops. Elements of two Russian infantry regiments (890 men and six cannons) were ordered to attack the eastern side of the northern part. At the same time, seven battalions (about 4,000 men) would attack the central and eastern parts from the south. About 70 cannons were ordered to fire on the second line of Polish defenses. This was to stop Polish reinforcements from reaching the fort. This time, several thousand Russians entered the northern part in strict military formations. The Polish defenders, now only 800 men, were not strong enough. Poles were pushed back into the trees. Maj. Lipski was killed. He was replaced by Maj. Dobrogoyski, who panicked and ordered a retreat, taking 500 men with him. The remaining 300 soldiers tried again to force the Russians out. But they were outnumbered 10 to 1. Around 10:30 AM, they had to retreat towards the central part. The central part, now commanded by Lt. Col. Wodzyński, held out against a large Russian group.

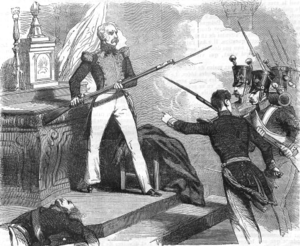

By then, the central part was defended by only 900 men and one cannon. The combined Russian forces were over 6,000 men. They prepared to storm it. Several attacks were stopped. But shortly after 11:00 AM, the Polish position was attacked from the north and south at the same time. The northern attack stalled. The southern attack was stopped with heavy losses. General Martynov was badly wounded. General Pahlen ordered another 2,300 men to attack from the other side. The Siberian regiment entered the fort. They forced the cannon crews, led by General Sowiński himself, to retreat within the church walls. The largest group of Polish soldiers fighting in front of the church was offered surrender. Sowiński and the rest of his crew laid down their weapons. Another group of Polish soldiers still defending the church fired at the Russians. Angered Russian soldiers massacred the prisoners of war, including General Sowiński. As Russian authorities later confirmed he died on the field of duty, Sowiński soon became a Polish national hero. He was made famous in a poem by Juliusz Słowacki.

The surrounded church was well prepared for defense. But its defenders were almost all wounded. By noon, the defenders were overwhelmed, and the Russians entered the church. The fight for Fort 56 was over. In total, the Russians lost at least 1,000 men killed during the storming of the fort. Polish casualties were no more than 300 killed and wounded. 1,230 soldiers and officers were captured. Only about 500 soldiers managed to retreat to Polish lines.

Fighting in Wola and Elsewhere

During the fights for Wola, only the second line of Polish artillery gave limited support. Krukowiecki later claimed he ordered others to help, but they apparently did not receive the order. General Ludwik Bogusławski, who commanded the second line, could have helped. But he couldn't see what was happening in Fort 56 because of the smoke and trees.

Paskevich expected a Polish counter-attack to retake the lost forts. So he ordered his troops to stop advancing. They rebuilt the walls and built new cannon positions facing the city. Further movement near Wola was blocked by Polish cannons from Fort 59. But within two hours, Russian engineers prepared Fort 56 to hold up to 20 cannons. Paskevich also sent riflemen forward to test Polish defenses around Fort 23. Polish cannons pushed back the Russian light infantry. But then they were attacked by Russian cannons and forced to flee. Only then did General Bogusławski realize Fort 56 might need help. He sent General Młokosiewicz with 1,000 men to check and possibly deliver supplies. Two Russian rifle regiments fled before his columns. Młokosiewicz's men almost reached the fort. But Russian cannons opened fire and caused dozens of Polish casualties. Młokosiewicz realized Fort 56 was lost and quickly retreated. Two Russian rifle regiments tried to follow, but Polish cannons defeated them.

This small Polish push probably made the Russians rethink their plans. They postponed further attacks until the next day. Paskevich was unsure what the Poles would do. He feared a Polish counter-attack or a split between his armies. He ordered all attacks in Wola to stop. His cannons continued to fight the Poles, but infantry was pulled back. Paskevich himself left to find General Muraviev's army to the south.

Around that time, General Małachowski arrived to inspect the front he had ignored. Informed of the loss of Fort 56, he ordered a counter-attack. But he was more worried about holding the second line. He sent only two battalions (1,240 men) out of 12 in reserve. The counter-attack began around 1:00 PM. It was supported by 14 horse cannons. General Bem kept 21 heavier cannons in reserve. As soon as the Poles left their walls, they came under fire from Russian cannons. Despite heavy fire, the Poles reached a point 500 meters (1,600 feet) south-east of Fort 56. There, they met elements of two Russian rifle regiments (about 1,800 men). Despite being outnumbered, the Polish force broke through and pushed the Russians back. But then they were defeated by Russian cannons on the eastern wall of Fort 56. When Russian reinforcements appeared on both sides, the Polish commander ordered a retreat. The Polish counter-attack failed. To make things worse, a large Russian force followed the retreating Poles.

The Russians attacked the second Polish line and broke through in many places. The Russian infantry's position was difficult. They had gone past the 14 Polish cannons sent forward by General Bem. This meant they were under cannon fire from the front, sides, and rear. Eventually, a counter-attack by the 4th Line Infantry Regiment pushed back the Russians. Several smaller Russian units broke through and tried to fortify wooden houses in Wola. But they were quickly surrounded and killed. At this point, around 1:00 PM, Małachowski wanted to organize another counter-attack on Fort 56. But Krukowiecki stopped him. He feared the Russians might attack further south and wanted to keep his reserves. The Poles stopped all attacks on the western front. Only the artillery remained active.

The Cannon Duel Continues

Between 1:00 PM and 2:00 PM, General Bem gathered at least 64 cannons near Forts 21, 22, and 23. He began firing on the Russian I Corps' cannons and infantry. The cannon attack lasted until 5:00 PM. The Russian forces were eventually forced to retreat behind the walls of the captured forts. Several times, Russian cavalry tried to charge the Polish cannon positions. But each time, they were stopped with grapeshot and canister shot. Eventually, the Russian cavalry pulled back. Half of the Russian artillery fought an intense cannon duel with the Poles. The other half shelled Wola and Polish positions behind the second line of defenses. Although this prepared the field for another Polish counter-attack, Krukowiecki would not risk it.

Paskevich held a meeting with his generals. Karl Wilhelm von Toll and many others insisted that the attack on Wola continue. But Paskevich was doubtful. The Russians still had 25,000 fresh troops. But dusk was near, and Paskevich feared his forces might lose order in the dark. He also thought an attack on Wola might be stopped by Polish forts still held (Forts 58, 59, and 60). He decided to postpone attacks until the next day. Paskevich also sent another message to Warsaw. But the Polish parliament quickly met and refused his offer of a cease-fire.

By then, the Russian battle plan was still unclear to the Polish Commander-in-Chief, General Krukowiecki. He was unsure if the main attack was on Wola or Królikarnia. He did not send many infantry troops to the western front. This was despite the southern line being safe and Russian attacks there being stopped one by one. Only a small group of horse artillery was sent to the second line near Wola. In the evening, General Krukowiecki called a government meeting. He said his forces were in a very difficult situation. He suggested resuming talks with Paskevich. He sent General Prądzyński to Paskevich's camp.

September 7: Negotiations and Renewed Fighting

First Talks

The two generals met on the edge of Wola early on September 7. Paskevich declared a cease-fire and invited Krukowiecki to meet him at 9:00 AM. The meeting was held in a tavern in Wola. Paskevich demanded that Warsaw and Praga be surrendered unconditionally. He also demanded that the Polish Army leave and give up their weapons in Płock. There, they would wait for the tsar's decision to pardon them or imprison them as rebels. Krukowiecki refused. He insisted that the uprising was not a rebellion, but a war between two independent states. He wanted Paskevich and Grand Duke Michael to promise Poland's independence and a general pardon. In return, the Poles would accept Nicholas as king again. The talks were heated. Around noon, the Polish commander left for Warsaw to talk with the parliament. Paskevich agreed to extend the cease-fire to 1:00 PM. He also agreed to continue talks even if fighting started again.

To get parliament's support, Krukowiecki asked General Prądzyński to speak for him. Krukowiecki's plan was to end the uprising at any cost. He wanted to return to the way things were before the war. He saw himself as the "savior of the homeland" who stopped more bloodshed. In his speech, Prądzyński greatly exaggerated the Russian strength. He also underestimated the Polish forces. He warned that the city's people would be massacred like in 1794 if fighting continued. He said that full independence under Nicholas was easy to get, which he knew was not true. He failed to convince the government and parliament that surrender was the only option. A heated debate went past the 1:00 PM deadline. The Russians restarted fighting, and cannons from both sides began another duel.

The Battle Situation

Both sides had similar losses the day before. Russian victories gave their cannons a clear shot into the suburbs of Czyste and Wola. This also boosted Russian soldiers' morale. They thought the battle was over once Fort 54 fell. But the battle was far from lost for the Poles. Although the Russians could now attack the third line of Polish defenses, their attacks could easily be hit from the side by Polish forts still held. Also, to support their advance with cannons, the Russian guns would have to be in the open.

The Polish battle plans remained the same. Fort 59 was left empty. Polish positions around Czyste and near Jerozolimskie Gate were slightly strengthened. But Polish forces remained almost equally split between the western and southern sectors. Unknown to the Poles, Russian orders for September 7 also did not change. The II Infantry Corps was to attack the forts at Czyste (21 and 22). The I Infantry Corps attacked further north (Forts 23 and 24). Muraviev's forces were to attack the Jerozolimskie Gate. The remaining forces continued their distraction attacks from the day before.

When cannon fire restarted around 1:30 PM, the Russian soldiers were not ready. The previous night had been very cold. Most Russian soldiers had no winter clothes and spent the night in the open. Many did not get food in the morning, and morale dropped. When the Russians began to organize, General Umiński correctly guessed that the main attack in his sector would be at the Jerozolimskie Gate. He reinforced the area with his reserves. He also sent the 1st Cavalry Division (1,300 men) closer to Czyste. Generals Małachowski and Dembiński planned to attack the side of the Russians attacking Wola. But when it became clear the Russians would attack further south, the plan was called off. The western sector returned to fixed defenses.

The Grand Battery

Around 1:30 PM, 132 Russian cannons and four mortars opened fire on Polish positions. This included 94 cannons of the Grand Battery. The Poles first responded with 79 cannons and 10 rocket launchers. But by 2:00 PM, General Bem moved another 31 cannons to a position right in front of the Russian artillery. To counter this, the Russian General von Toll ordered his Grand Battery to move 100 meters (330 feet) closer to the Poles. This exposed his side to Polish cannons hidden to the south. The Russians suffered losses, and the Grand Battery had to split into two units. To make things worse, many batteries had to stop firing and pull back due to lack of ammunition.

Seeing that cannons alone would not break the Poles, General von Toll made a new attack plan. He decided to ignore Paskevich's order not to assault Warsaw. Although dusk was near, von Toll ordered a full attack on both the western and southern fronts. Since there was no time for proper cannon preparation, von Toll wanted to overwhelm the defenders with sheer numbers. This would mean more losses from Polish cannons. To distract the Polish cannons at Czyste, Muraviev's forces would lead the attack directly towards the Jerozolimskie Gate. Before 3:00 PM, von Toll sent General Neidhardt to Paskevich to get his approval. But Paskevich flatly refused. He ordered his subordinate to continue shelling the Polish forts with cannons until at least 4:00 PM. Since the Russian commander-in-chief was away, von Toll decided to act despite Paskevich's orders.

Muraviev's Attack and Retreat

Around 3:00 PM, large groups of Russian troops began preparing to attack Polish positions near the Jerozolimskie Gate. A strong force under Muraviev and Nostitz took positions on both sides of the road to Cracow. The attack began around 4:00 PM. The left column suffered many losses. But it reached Fort 74, only to be met by Polish reinforcements. Two thousand Russians fought with less than 850 Poles inside the fort. But the Poles defeated them in a bayonet charge, and the Russians had to retreat. Since the attack failed and the Polish cannons were still active, von Toll decided to use his cavalry reserves. Two cavalry regiments (1,200 cavalry) followed a road and were ordered to charge the Polish cannons from behind. The Poles saw them coming and had enough time to prepare. When the Russian cavalry changed formation, Polish cannons opened fire with canister shot, scattering them. The Russian commander reorganized his forces and repeated the charge. But the Russians were again stopped before reaching the Polish cannon positions. One Russian regiment alone lost over 200 men out of 450 in the charge.

After half an hour, the Russians finally stormed the walls of Fort 74. They defeated the Polish battalion defending it. This forced the Polish mobile cannons in Czyste to fall back. Meanwhile, the Russian right column approached Fort 72. Only 200 men defended the fort. Seeing this, the Polish commander ordered his cavalry reserve to charge the Russian infantry. Russian grenadiers stormed the walls of Fort 72. But they were stopped and forced back behind the moat. There, the Polish cavalry charged them. The Russians formed squares, but were defeated and forced to retreat. To counter the threat, General Nostitz sent his own cavalry reserve. A cavalry battle began.

This saved the Russian infantry. The Polish cannons' line of fire was blocked by both Polish and Russian cavalry. Both commanders sent more cavalry into the fight. Soon, both sides had similar numbers, with 550 cavalrymen on each side. Both forces soon lost order. The battle became a series of duels between Polish and Russian cavalry. The Poles were initially victorious. They managed to wound both General Nostitz and General von Sass. But then they were attacked by more Russian reinforcements and had to retreat. This forced some Polish cannon crews to retreat to the third line of defenses. The Russian Guard Hussar Regiment pursued the fleeing Polish cavalry. They were met by Polish cavalry reinforcements. But the Russian veterans broke through this new Polish line. The Polish regiment broke and began to retreat, followed by the Russians. General Umiński ordered his infantry and cannons to open fire on the mass of cavalry, both Polish and Russian. Small groups of Russians retreated. Others, in a battle frenzy, tried to storm the heavily defended gates of Warsaw. They were killed by Polish infantry. A small group succeeded, and the last of them was killed as far as the gate of the Ujazdów Palace, 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) into the city. The cavalry battle ended with almost all three regiments involved being destroyed.

Although the Poles stopped and defeated the Russian cavalry, their charge caused widespread panic among the Poles. The defenders of Fort 72 abandoned their positions, leaving their cannons behind. They retreated to Fort 73 without a fight. Likewise, the defenders of Fort 73 panicked. Their commander ordered his soldiers to block the cannons and leave the main wall. He expected Russian cavalry to enter from behind. This allowed the Russian infantry to capture Fort 72 and a fortified inn. They headed towards Fort 73 unopposed. Polish officers managed to stop the panic just in time. Their infantrymen fired on the approaching Russians and forced them to retreat. Fort 72 remained in Russian hands.

The panic among the Poles convinced Muraviev to renew his attack with fresh forces. Russian grenadiers, reinforced with two battalions, outflanked Fort 73 from the north. They captured a brickyard and another fortified inn directly behind it. Its defenders offered little resistance before retreating in disorder. The situation seemed critical. The Russians now held a large part of the second line of Polish defenses.

Despite the serious situation, the Polish defenders still had enough fresh troops to counter-attack. The Russians' recently captured positions were too far ahead of their cannons. They were all under accurate fire from Polish fixed cannon positions on the third line of defenses. They were also under fire from many mobile cannon batteries. Forts 72 and 73, as well as the inns and the brickyard, received constant grapeshot fire. Under fire from all sides, the Russians had to hide behind the outer sides of the walls. They could not fire back or even see the field in front of them. Polish riflemen approached the inn almost unopposed and retook it. Soon after, they retook the brickyard. The Russians also abandoned the two forts. Although Russian light infantry tried to retake them, they failed. Around 4:45 PM, Józef Bem's cannons were free to leave the safety of the inner defenses. They returned to the battlefield and opened fire on the Grand Battery. Despite over three hours of intense fighting in the west, the commander of the southern sector, General Małachowski, did not send reinforcements to the western defenders.

Russian Attack in the West

Although Muraviev's attack failed, it forced the Polish cannons to reduce pressure on the Russian Grand Battery. This allowed the Grand Battery to support the main Russian attack on the westernmost Polish defenses. By then, the Grand Battery could shell the walls of the second line easily. This damaged both the defenses and the morale of the crews. Polish infantrymen in the forts were ordered to lie down behind the gabions, which reduced losses. Soldiers in the open had no such cover and suffered casualties. The Grand Battery also silenced some of the cannons in Forts 21, 22, and 23.

General von Toll initially planned to order his infantry to start the attack at 4:00 PM. But Paskevich, through his aides, ordered him to postpone the attack until 4:45 PM. Eventually, around 5:00 PM, von Kreutz's army advanced towards Forts 21 and 22 in two columns. Russian horse artillery reached a position 200 paces (150 meters) from Fort 22. They began shelling the defenders at close range. Already shaken by the Grand Battery's fire, the Poles abandoned the fort and retreated before the surprised Russian infantry approached. This was a rare example of cannons capturing a fortified position without other forces. Meanwhile, the fighting for the nearby Fort 22 was heavy. In the end, its defenders fell almost to the last man.

At the same time, von Pahlen's Corps attacked forts 23 and 24, and the Polish position at the Evangelical Cemetery. Heavy fighting followed. Many Russian commanders, including Paskevich, suggested postponing further fighting until the next day. General von Toll insisted on reaching the last line of Polish defenses before sunset. The surrounding forts changed hands many times. But in the end, most of them remained in Russian hands by 10:00 PM, when the Russians stopped fighting. Around midnight, General Berg arrived in Warsaw with a new ultimatum signed by Paskevich.

Polish Surrender

General Prądzyński was again sent to the Russian headquarters. There, he was greeted by Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich, as Paskevich had been wounded. Although Michael believed the Poles were trying to gain time, Prądzyński convinced him to send General Berg to Warsaw. Berg carried a draft of an unconditional surrender agreement. The agreement said that the Polish Army was free to leave the city. A two-day cease-fire would begin. Warsaw would be spared the horrors it experienced during the 1794 siege. No political terms were included. Around 5:00 PM, Prądzyński and Berg arrived in Warsaw. Krukowiecki generally agreed with the Russian terms, but thought they were too harsh. Berg and Prądzyński then returned to Russian headquarters. Grand Duke Michael agreed to allow the Polish Army free passage to Modlin and Płock. He also offered a pardon to all fighters and to exchange prisoners. The new terms were more than acceptable to Krukowiecki. When Prądzyński returned, the more liberal group in the government gained a temporary majority. Krukowiecki was removed from power. Bonawentura Niemojowski became head of government, and General Kazimierz Małachowski became Commander-in-Chief.

September 8: The End of the Battle

The ultimatum demanded that Warsaw be surrendered immediately, along with the bridge and the suburb of Praga. It threatened the complete destruction of the city the next day. After a heated debate, the new Polish leaders decided to agree by 5:00 AM. Małachowski sent a letter to Paskevich. He told him the army was withdrawing to Płock "to avoid further bloodshed and to prove its loyalty." The letter also hoped the Russians would allow free passage to troops who couldn't leave by the deadline. It also hoped the army would honor the terms negotiated with Grand Duke Michael. The surrender of Warsaw was not a formal agreement. It was the result of long talks. The Russians initially respected its terms.

The Polish Army withdrew across the Vistula and continued north towards the Modlin Fortress. The Polish parliament, Senate, and many civilians also left the city "in grim silence." Many soldiers, including high-ranking officers, decided to stay in the city and give up their weapons. Up to 5,000 soldiers stayed in Warsaw, along with 600 officers. Food stores were opened, and their contents were given to the civilians.

The next evening, Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich entered the city leading his Imperial Guard. Warsaw had surrendered.

What Happened After

Even though no large-scale evacuation of supplies from Warsaw was ordered, the Modlin Fortress was ready for a long siege. Its storage areas had over 25,000 cannonballs, almost 900,000 musket and rifle rounds, and enough food for several months. The Polish government's treasury was still intact. It held more than 6.5 million złotys (Polish currency).

The fall of Warsaw meant the fall of Poland to both Poles and foreigners. To remember the crushing of the November Uprising, Alexander Pushkin wrote "On the Taking of Warsaw." He praised the surrender of Poland's capital as Russia's "final triumph." Other writers and poets also celebrated. Soon after, the tsar almost completely dismantled the Kingdom of Poland. Its constitution was removed. Russian officials took over the government. Warsaw University was closed.

News of Warsaw's fall spread quickly. The French government, which had been pressured to support the Poles, was relieved. The French Minister of Foreign Affairs Horace Sébastiani declared to the French parliament that "Order now reigns in Warsaw." This phrase became famous and was often mocked by those who supported Poland's cause. The Russian capture of the city in 1831 caused a wave of sympathy for Poles. Several towns in the United States changed their names to Warsaw after hearing the news. These included Warsaw, Virginia and Warsaw, Kentucky.

Shortly after the battle, in December 1831, the Russian authorities issued a medal "For the Taking of Warsaw by Assault in 1831" to Russian veterans. A monument "To the Captors of Warsaw" was built near the former Redoubt 54. It was torn down after Poland regained independence in 1918. The spot is now home to a monument to Juliusz Konstanty Ordon and his soldiers. There are plans to move this monument closer to the actual site of the redoubt.

The Battle of Warsaw is remembered on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Warsaw. The inscription reads "WARSZAWA 6–8 IX 1831".

Images for kids

-

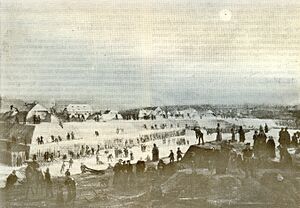

Pontoon bridge over the Vistula on an 1831 painting by Marcin Zaleski

-

Russian hussars charging towards Warsaw (7 September 1831), painting by Mikhail Lermontov

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |