Beryl May Dent facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Beryl May Dent

MIEE

|

|

|---|---|

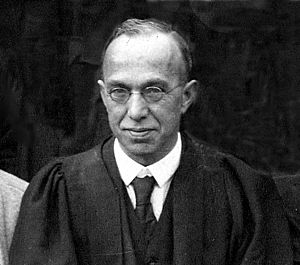

Dent in 1928

|

|

| Born | 10 May 1900 Chippenham, Wiltshire, England

|

| Died | 9 August 1977 (aged 77) Worthing, West Sussex, England

|

| Resting place | Worthing Crematorium (ashes interred) |

| Alma mater | |

| Awards | Ashworth Hallett scholarship 1923 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | Some theoretical determinations of crystal structure (1927) |

| Academic advisors | John Lennard-Jones |

Beryl May Dent (born May 10, 1900 – died August 9, 1977) was an amazing English scientist. She was a mathematical physicist, a librarian for technical information, and one of the first people to program early computers. She used these computers to solve tricky problems in electrical engineering.

Beryl was born in Chippenham, England. Her parents were both schoolteachers. In 1923, she earned a top degree in applied mathematics from the University of Bristol. She then received a special scholarship and went to Newnham College, part of the University of Cambridge.

In 1925, Beryl returned to Bristol University as a researcher in the Physics Department. She worked with John Lennard-Jones, a professor who studied how atoms and molecules interact. They published several important papers together. Their work helped create the foundation for her master's degree thesis. Later, their ideas even helped develop atomic force microscopy, a way to see tiny surfaces.

In 1930, Beryl joined Metropolitan-Vickers, a big electrical company in Manchester. She became their technical librarian, helping scientists and engineers find information. She also became a leader in the company's computing section. She helped use early computers to solve problems in electrical design. Beryl retired in 1960 and passed away in 1977.

Contents

Early Life and School Days

Beryl May Dent was born on May 10, 1900, in Chippenham, England. Her parents, Agnes and Eustace Edward Dent, were both teachers. When Beryl was very young, her family moved to Warminster because her father became the head teacher of a new school there.

Beryl and her younger sister, Florence Mary, sometimes performed on stage with their father. He was part of the Warminster Operatic Society. Beryl even sang a solo in a Japanese operetta called Princess Ju-Ju! She also performed in a fan dance.

Education at Warminster County School

From 1909, Beryl attended Warminster County School, where her father was the head teacher. She was a bright student. In 1914, she earned First Class Honours in the University of Oxford Junior Local Examination. This helped her get a scholarship from the school.

She continued to do well, especially in French. In 1918, she tried for a scholarship in mathematics at Somerville College, Oxford, a women's college at Oxford University. She was highly praised, even though she didn't get the scholarship.

University of Bristol and Cambridge

In 1918, during the First World War, Beryl worked at the Royal Aircraft Establishment. This was a place where women were starting to get jobs in engineering and math. In 1919, she began studying for her Bachelor of Arts degree at the University of Bristol. Bristol was one of the first universities in England to accept women equally with men.

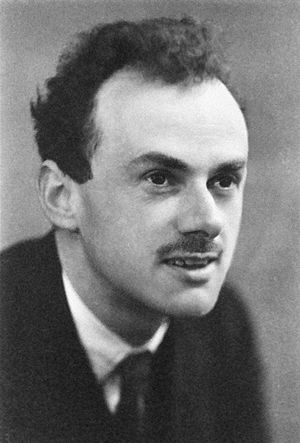

Later, she joined the honours course in mathematics. A famous physicist named Paul Dirac also joined the course. They were taught by excellent professors from Cambridge. Beryl focused on applied mathematics, which uses math to solve real-world problems.

In June 1923, Beryl graduated from Bristol with a top degree in applied mathematics. She then received a scholarship to study at Newnham College in the University of Cambridge. She spent a year there, but at that time, Cambridge University did not give degrees to women graduates.

Working as a Scientist and Engineer

Teaching and Research at Bristol

After leaving Cambridge, Beryl taught mathematics for a year at the High School for Girls in Barnsley. However, there weren't many jobs for women in math and engineering back then, besides teaching.

In 1925, she returned to the University of Bristol as a research assistant in the Physics Department. Her salary was paid by a government research department.

In 1927, John Lennard-Jones became a professor of theoretical physics at Bristol. Beryl became his research assistant. Lennard-Jones was a pioneer in understanding forces between atoms and molecules. Beryl was one of his first helpers. They published six papers together from 1926 to 1928. Their work helped explain the forces inside crystals.

Beryl earned her Master of Science (MSc) degree in 1927 for her research. She also became the first part-time librarian for the Physics Department.

In 1929, Lennard-Jones left Bristol to study quantum mechanics. Beryl wrote one more paper about how surface ions affect crystals before she also left Bristol. In November 1929, she got a new job as a technical librarian at Metropolitan-Vickers in Manchester.

Metropolitan-Vickers and Early Computers

Metropolitan-Vickers was a major British company that made electrical equipment. Beryl joined their research department as a technical librarian in 1930. She was one of only two senior women in the research department. She was hired for her technical skills, which was unusual for a librarian at the time.

Beryl was active in the Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux (ASLIB). She helped start their local branch and gave presentations about the company's library. Technical librarianship was a new science career in Britain between the World Wars. It was one of the few professional jobs open to both women and men.

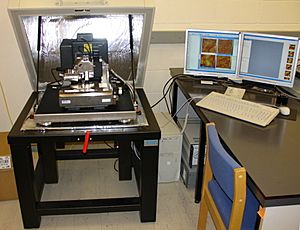

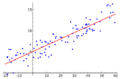

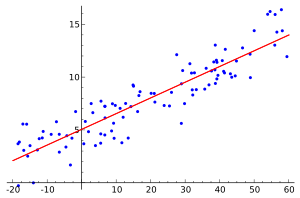

Beryl continued to publish scientific papers. She helped develop numerical methods for solving complex equations using a machine called a differential analyser. This machine was an early type of analogue computer. She also created a new method for finding the "best fit" line for data points, which is called the reduced major axis method.

Later in her career, Beryl became the leader of the computation section at Metropolitan-Vickers. This meant she was in charge of using computers to solve problems. She also supervised a section that studied semiconducting materials. She joined the Women's Engineering Society and wrote papers about how digital computers could be used in electrical design.

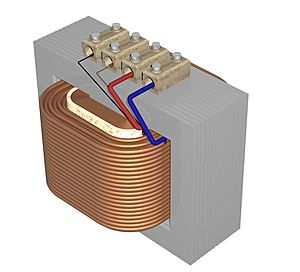

In 1956, Beryl and Brian Birtwistle showed how fast digital computers could help electrical engineers. They used the Ferranti Mark 1 computer at the University of Manchester to solve three problems:

- How voltage spreads on transformer windings.

- How electrical ripple affects a device called a transductor.

- The starting power of a synchronous motor.

The computer solved the first problem in about five hours. Doing it by hand would have taken three months! This showed how much computers could speed up engineering design. Beryl retired from Metropolitan-Vickers in May 1960.

Personal Life

In the 1920s, Beryl lived at Clifton Hill House, a university dorm for women at the University of Bristol. She was very sad to leave Bristol, saying she had "many happy memories" there.

Beryl was involved in the university's alumni association. She also helped raise money for a chemistry chair at Cheeloo University in China. She gave presentations to groups like the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom to spread awareness.

After moving to Manchester in 1930, Beryl shared a house with a friend from university. On weekends, she enjoyed hiking to Hebden Bridge. She also learned to figure skate at the Ice Palace, a former ice rink in Manchester.

In 1930, Beryl attended a science conference in Bristol. She heard Paul Dirac present a paper. She later said, "I heard a striking paper by Dirac, who was a student with me, who is now a very famous person, as I always knew he would be... I now go about boasting that I was in the same class!"

Beryl never married. She believed that family responsibilities could be a "wastage" of a woman's training. However, she also thought that women leaving work to marry could create opportunities for other women. She believed married women could return to work later in life.

Later Life and Death

In 1962, Beryl and her mother moved to Sompting, a village in West Sussex. Her mother passed away in 1967. Beryl's sister, Florence Mary, also lived in the house until her death in 1986.

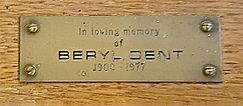

Beryl May Dent died at Worthing Hospital on August 9, 1977. She donated her body for medical study. Her ashes were later buried at Worthing Crematorium. A memorial to Beryl is also found at the Church of St Mary the Blessed Virgin in Sompting. A brass plaque on the bishop's chair reads: "In loving memory of BERYL DENT 1900 – 1977."

Her Impact on Technology

Beryl May Dent's work helped advance several areas of science and engineering.

Atomic Force Microscopy

In 1928, Beryl and Lennard-Jones published papers that described how to calculate the electric field near a thin salt crystal surface. They showed that the force on a single ion (a charged atom) decreases very quickly as it moves away from the surface.

This idea later became important for atomic force microscopy (AFM). AFM is a special type of microscope that can create images of surfaces at a very tiny scale, even down to individual atoms. Beryl's work helped show that this "non-contact" imaging is possible only when the microscope's tip is very close to the sample.

Reduced Major Axis Regression

When scientists analyze data, they often try to find a "line of best fit" to show the relationship between two variables. This is called linear regression. Usually, it's assumed that one variable is measured perfectly, and the other has errors.

However, in real experiments, both variables can have errors. Beryl Dent was one of the first to develop a method called "reduced major axis (RMA) regression" to handle errors in both variables. She showed how to find the most likely "true positions" of data points, even when the errors are unknown. Her method is still important today, especially when scientists don't know exactly how errors are distributed in their data.

Electrical Design with Digital Computers

In the 1950s, electrical engineers rarely used digital computers. Programming them was difficult and time-consuming. Beryl Dent and Brian Birtwistle changed this. In 1956, they presented a paper showing how digital computers could greatly help electrical engineers.

They used the Ferranti Mark 1 computer to solve three real-world problems:

- Calculating how impulse voltage spreads on transformer windings.

- Understanding how electrical ripple affects transductor performance.

- Figuring out the starting torque of a synchronous motor.

Their work showed that computers could do complex calculations much faster than humans. For example, a calculation that took three months by hand could be done in five hours by the computer. Beryl's research helped engineers use computers to design better electrical products more efficiently.

Images for kids

-

Paul Dirac, Dent's fellow student on the honours course in mathematics at Bristol

-

In 1923, Dent was accepted as a postgraduate research student by at Newnham College, University of Cambridge

-

The former High School for Girls, Barnsley, where Dent taught mathematics after leaving Newnham College

-

John Edward Lennard-Jones, Dent's advisor and co-author at Bristol in the 1920s

-

Differential analyser designed by Douglas Hartree, at the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester

-

The Ice Palace skating rink in Cheetham Hill where Dent learnt to figure skate in the early 1930s

-

An atomic force microscope on the left with controlling computer on the right. Dent's work had direct application to the development of atomic force microscopy

-

Graph with x and y axes showing scattered points with a line of best fit. Linear regression attempts to model the relationship between two variables by fitting a linear equation (straight line) to observed data

-

Illustration of transformer windings

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |