Bill Watterson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Bill Watterson

|

|

|---|---|

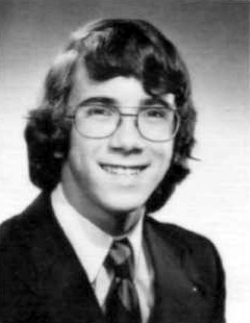

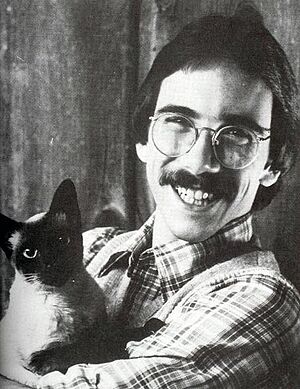

Watterson in 1981

|

|

| Born |

William Boyd Watterson II

July 5, 1958 Washington, D.C., U.S.

|

| Education | Kenyon College (BA) |

| Occupation | Cartoonist |

| Signature | |

|

|

William Boyd Watterson II (born July 5, 1958) is an American cartoonist. He created the famous comic strip Calvin and Hobbes. This comic strip was published in newspapers from 1985 to 1995. Bill Watterson decided to end Calvin and Hobbes because he felt he had done everything he wanted to with the comic. He is known for not liking how comic strips were sold and licensed. He also worked to make newspaper comics seen as a true art form. After Calvin and Hobbes ended, he chose to live a more private life. Watterson was born in Washington, D.C., and grew up in Chagrin Falls, Ohio. The suburban Ohio setting helped inspire the world of Calvin and Hobbes. Watterson now lives in Cleveland Heights, Ohio.

Contents

Early Life and Art Beginnings

Bill Watterson was born on July 5, 1958, in Washington, D.C.. His parents were Kathryn and James Watterson. His father worked as a patent attorney, helping people protect their inventions. In 1965, when Bill was six, his family moved to Chagrin Falls, Ohio. This town is a suburb near Cleveland. Bill has a younger brother, Thomas, who lives in Austin, Texas. Thomas used to be a musician and now works as an educator.

Watterson drew his first cartoon when he was eight years old. He spent a lot of his childhood drawing by himself. This continued through his school years. During this time, he found comic strips like Pogo, Krazy Kat, and Peanuts. These comics greatly inspired him to become a professional cartoonist. Once, in fourth grade, he wrote a letter to Charles M. Schulz, the creator of Peanuts. Schulz wrote back, which surprised and impressed Watterson a lot. His parents always encouraged his art. They remembered him as a "conservative child" who was imaginative. He was not like the wild character Calvin he later created. Watterson used his cartooning skills in school. He made superhero comics with friends and drew for the school newspaper and yearbook.

College Years and Character Names

After high school, Watterson went to Kenyon College. He studied political science there. He had already decided to become a cartoonist. He thought studying politics would help him draw cartoons about current events. He kept improving his art skills. In his second year, he painted Michelangelo's Creation of Adam on his dorm room ceiling. He also drew cartoons for the college newspaper. Some of these included early versions of his "Spaceman Spiff" character. Watterson graduated from Kenyon in 1980 with a Bachelor of Arts degree.

Later, when he was naming characters for his comic strip, he chose Calvin and Hobbes. Calvin was named after John Calvin, a 16th-century religious thinker. Hobbes was named after Thomas Hobbes, a 17th-century philosopher. Watterson said this was a nod to his political science studies at Kenyon. He explained that Calvin believed in "predestination," and Hobbes had a "dim view of human nature."

Cartooning Career

Early Work and Challenges

Watterson was inspired by Jim Borgman, a political cartoonist for The Cincinnati Enquirer. Borgman also went to Kenyon College. Watterson wanted to follow a similar path. Borgman even offered him support. After graduating in 1980, Watterson got a trial job at the Cincinnati Post. This was a newspaper that competed with the Enquirer.

Watterson quickly found the job challenging. He was not familiar with Cincinnati politics, as he grew up near Cleveland. This made it hard for him to do his job well. The Post fired Watterson before his contract ended. After that, he worked for four years at a small advertising agency. He designed grocery ads while also working on his own cartoons. He also contributed to a magazine called Target: The Political Cartoon Quarterly. As a freelance artist, Watterson also drew for other things. These included album covers for his brother's band, calendars, and posters.

Creating Calvin and Hobbes

Watterson has said he works for his own happiness. He told a graduating class in 1990, "It's surprising how hard we'll work when the work is done just for ourselves." Calvin and Hobbes first appeared in newspapers on November 18, 1985. In a book about the comic, he mentioned that Peanuts, Pogo, and Krazy Kat were big influences on his work. He also wrote the introduction for a book about Krazy Kat. Watterson's drawing style also shows the influence of Little Nemo in Slumberland by Winsor McCay.

Like many artists, Watterson put parts of his own life into his work. His love for cycling was included. Memories of his father's talks about "building character" also appeared. His strong opinions on selling merchandise and big companies were also part of the comic. Watterson's own cat, Sprite, greatly inspired the look and personality of Hobbes.

Watterson spent much of his career trying to change how newspaper comics were treated. He believed that the artistic value of comics was being ignored. He also felt that the space they got in newspapers kept shrinking. He thought this was due to publishers who didn't think ahead. He also stated that art should not be judged by where it appears. He believed there is only art, not "high" art or "low" art.

Protecting His Characters

For many years, Watterson fought against pressure from publishers. They wanted to sell merchandise based on Calvin and Hobbes. He felt that putting Calvin and Hobbes images on mugs, stickers, and T-shirts would make the characters less special. He believed it would harm the creative process and the experience of reading the comic.

Watterson refused to license his creations. He said that his first contract was very unfair. He signed it because he was a new artist and happy to find a company willing to give him a chance. He explained that the contract was so one-sided that the company could license his characters even if he didn't want them to. They could even fire him and continue Calvin and Hobbes with a new artist. Eventually, Watterson won this fight. He was able to change his contract to get all rights to his work. He later said this fight made him very tired. It even led to him taking a nine-month break in 1991.

Despite Watterson's efforts, many unofficial items were made. These included things showing Calvin and Hobbes doing inappropriate things. Watterson has said, "Only thieves and vandals have made money on Calvin and Hobbes merchandise."

Changing Sunday Comic Layouts

Watterson was not happy with the usual layout for Sunday comic strips. When he started drawing, the typical Sunday comic had three rows with eight panels. This took up half a newspaper page. Some newspapers had less space and would make the strip smaller. A common way to do this was to cut out the top two panels. Watterson felt this forced him to waste space on jokes that didn't always fit the story.

When he returned from his first break, Watterson talked with his company about a new layout for Calvin and Hobbes. This new format would let him use the space better. It would also almost force newspapers to print it as a half-page. His company agreed to sell the strip only as a half-page. This made some newspapers angry. Editors and other cartoonists criticized Watterson. Eventually, the company offered newspapers a choice. They could have the full half-page or a smaller version. Watterson admitted this meant his comic appeared in fewer papers. But he felt it was worth it because readers got a better comic. He also said he wouldn't apologize for drawing a popular comic.

The End of Calvin and Hobbes

On November 9, 1995, Bill Watterson announced that Calvin and Hobbes would end. He sent a letter to newspaper editors. In his letter, he said it was a hard decision. He felt his interests had changed. He also believed he had done all he could with daily deadlines and small panels. He wanted to work at a slower pace with fewer artistic compromises. He thanked the newspapers for carrying his comic. He said drawing the strip was a privilege and a pleasure.

The very last Calvin and Hobbes comic strip was published on December 31, 1995.

Life After Calvin and Hobbes

Since Calvin and Hobbes ended, many people have tried to reach Watterson. Reporters from newspapers tried to contact him in 1998 and 2003. But Watterson is very private and avoids the media. Since 1995, Watterson has focused on painting. At one point, he drew landscapes of woods with his father. He has stayed out of the public eye. He has not shown interest in bringing the strip back. He also doesn't want to create new works based on the characters or start new business projects. However, he has published several Calvin and Hobbes "treasury collection" books. He does not sign autographs or allow his characters to be licensed. Watterson used to secretly place autographed copies of his books in a bookstore in his hometown. He stopped when he found out these signed books were being sold online for very high prices.

Watterson rarely gives interviews or appears in public. Some of his longer interviews include a story in The Comics Journal in 1989. He also gave an interview to Honk Magazine in 1987. Another interview appeared in a 2015 exhibition book about Watterson. In 1999, he wrote a short piece for the Los Angeles Times. This was to mark the retirement of Peanuts creator Charles M. Schulz.

Around 2003, a reporter from The Washington Post tried to interview Watterson. The reporter sent a rare book to Watterson's parents with a message. He waited in his hotel for Watterson to contact him. The next day, Watterson's editor called to say the cartoonist would not come.

In 2004, Watterson and his wife, Melissa, bought a home in Cleveland Heights, Ohio. In 2005, they moved there from their home in Chagrin Falls. In October 2005, Watterson answered 15 questions from readers. In October 2007, he wrote a review of a book about Charles M. Schulz for The Wall Street Journal.

In 2008, he wrote a foreword for the first book collection of Cul de Sac by Richard Thompson. In 2011, Watterson sent a painting to a company called Andrews McMeel. It was an oil painting of a character from Cul de Sac. He made it for a project to raise money for Parkinson's disease research. This was in honor of Richard Thompson, who was diagnosed in 2009. Watterson's company said this was the first new artwork they had seen from him since Calvin and Hobbes ended in 1995.

In 2009, Nevin Martell published a book called Looking for Calvin and Hobbes. It was about the author's search for an interview with Watterson. He interviewed friends and family but never met the artist.

In 2010, The Plain Dealer interviewed Watterson. This was for the 15th anniversary of Calvin and Hobbes ending. He explained his decision to stop the comic. He said, "By the end of ten years, I'd said pretty much everything I had come there to say. It's always better to leave the party early." He felt that if he had kept going, people would have gotten tired of the strip. He believes Calvin and Hobbes is still popular today because he chose to stop when he did.

In October 2013, Mental Floss magazine published an interview with Watterson. This was only his second interview since the strip ended. Watterson again confirmed he would not bring back Calvin and Hobbes. He was happy with his decision. He also shared his thoughts on how the comic strip industry was changing. He said, "Personally, I like paper and ink better than glowing pixels, but to each his own." He noted that comics are now more accepted as serious art. But he also felt that mass media is changing, and audiences are splitting up. He thought comics might have less widespread cultural impact and make less money. He found these changes unsettling but understood that the world moves on. He believed new media would change comics, but they would still find a way to be important.

In 2013, a documentary called Dear Mr. Watterson was released. It explored how Calvin and Hobbes affected culture. Watterson himself did not appear in the film. On February 26, 2014, Watterson published his first cartoon since Calvin and Hobbes ended. It was a poster for the documentary Stripped. In 2014, Watterson helped write a book called The Art of Richard Thompson.

In June 2014, Bill Watterson drew three Pearls Before Swine comic strips. This happened after a friend connected him with cartoonist Stephan Pastis. They talked through email. Pastis said this unexpected teamwork was like getting "a glimpse of Bigfoot." Watterson told The Washington Post that he and Stephan wanted to do a fun collaboration. They then used the result to raise money for Parkinson's research in honor of Richard Thompson. When Stephan Pastis returned to his own strip, he honored Watterson. He hinted at the very last Calvin and Hobbes strip from December 31, 1995.

On November 5, 2014, a poster drawn by Watterson was shown. It was for the 2015 Angoulême International Comics Festival. Watterson had won a major award there in 2014. On April 1, 2016, for April Fools' Day, Berkeley Breathed posted on Facebook that Watterson had given him the "franchise." He then posted a comic with Calvin, Hobbes, and Opus. The comic was signed by Watterson, but how much he was involved was not clear. Breathed posted another "Calvin County" strip with Calvin and Hobbes, also "signed" by Watterson, on April 1, 2017. He also posted a fake New York Times story about the comics joining together. Berkeley Breathed included Hobbes in a November 27, 2017, strip. Hobbes also appeared in June 9, 11, and 12, 2021, strips.

Art Exhibitions

In 2001, the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at Ohio State University held an exhibition of Watterson's Sunday strips. He chose thirty-six of his favorite Sunday comics. The exhibit showed both the original drawing and the finished colored version. Most pieces had Watterson's personal notes. Watterson also wrote an essay for the exhibit, called "Calvin and Hobbes: Sunday Pages 1985–1995." It opened on September 10, 2001, and closed in January 2002. A book with the same title was also published.

From March 22 to August 3, 2014, Watterson had another exhibition at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. For this event, Watterson also took part in an interview with the school. A book called Exploring Calvin and Hobbes was released with the exhibit. This book included a long interview with Bill Watterson. It was conducted by Jenny Robb, the museum's curator.

New Work: The Mysteries

Watterson released his first new published work in 28 years on October 10, 2023. It is called The Mysteries. It is an illustrated "fable for grown-ups" about things beyond human understanding. Watterson worked with illustrator John Kascht on this book.

Awards and Honors

Bill Watterson has received many awards for his work. He won the National Cartoonists Society's Reuben Award twice. He won in 1986 and again in 1988. His second Reuben win made him the youngest cartoonist to receive this honor. He was only the sixth person to win it twice. In 2014, Watterson won the Grand Prix at the Angoulême International Comics Festival. This award recognized his entire body of work. He was only the fourth non-European cartoonist to win this award in the festival's first 41 years.

- 1986: Reuben Award, Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year

- 1988: Reuben Award, Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year

- 1988: National Cartoonists Society, Newspaper Comic Strips Humor Award

- 1988: Sproing Award, for Tommy og Tigern (Calvin and Hobbes)

- 1989: Harvey Award, Special Award for Humor, for Calvin and Hobbes

- 1990: Harvey Award, Best Syndicated Comic Strip, for Calvin and Hobbes

- 1990: Max & Moritz Prize, Best Comic Strip, for Calvin and Hobbes

- 1991: Harvey Award, Best Syndicated Comic Strip, for Calvin and Hobbes

- 1991: Adamson Award, for Kalle och Hobbe (Calvin and Hobbes)

- 1992: Harvey Award, Best Syndicated Comic Strip, for Calvin and Hobbes

- 1992: Eisner Award, Best Comic Strip Collection, for The Revenge of the Baby-Sat

- 1992: Angoulême International Comics Festival, Prize for Best Foreign Comic Book, for En avant tête de thon!

- 1993: Eisner Award, Best Comic Strip Collection, for Attack of the Deranged Mutant Killer Monster Snow Goons

- 1993: Harvey Award, Best Syndicated Comic Strip, for Calvin and Hobbes

- 1994: Harvey Award, Best Syndicated Comic Strip, for Calvin and Hobbes

- 1995: Harvey Award, Best Syndicated Comic Strip, for Calvin and Hobbes

- 1996: Harvey Award, Best Syndicated Comic Strip, for Calvin and Hobbes

- 2014: Grand Prix, Angoulême International Comics Festival

- 2020: Inducted into the Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame

See also

In Spanish: Bill Watterson para niños

In Spanish: Bill Watterson para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |