Brian Josephson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Brian Josephson

|

|

|---|---|

Josephson in 2004

|

|

| Born |

Brian David Josephson

4 January 1940 Cardiff, Wales

|

| Education | Cardiff High School |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge (BA, MA, PhD) |

| Known for | Josephson effect (1962) |

| Spouse(s) |

Carol Anne Olivier

(m. 1976; died 2025) |

| Children | 1 |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Condensed matter physics |

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | Non-linear conduction in superconductors (1964) |

| Doctoral advisor | Brian Pippard |

Brian David Josephson (born 4 January 1940) is a Welsh theoretical physicist. He is a professor emeritus (meaning he has retired but keeps his title) of physics at the University of Cambridge. He is famous for his important work on superconductivity and quantum tunnelling.

In 1973, he shared the Nobel Prize in Physics with Leo Esaki and Ivar Giaever. He won the award for discovering the Josephson effect in 1962. At the time, he was only 22 years old and a PhD student at Cambridge.

Josephson spent his whole career working with the Theory of Condensed Matter group at Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory. He became a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge in 1962. He was a Professor of Physics from 1974 until he retired in 2007.

In the early 1970s, Josephson became interested in transcendental meditation. He started looking into ideas that were outside the usual boundaries of science. He created the Mind–Matter Unification Project at Cavendish. This project explored ideas like how nature might have intelligence, how quantum mechanics (the physics of very tiny things) might connect to consciousness (our awareness), and how science and Eastern spiritual ideas could fit together. He has also supported topics like parapsychology (the study of psychic abilities), water memory (the idea that water can remember substances it once held), and cold fusion (nuclear reactions at room temperature). Because of these interests, some other scientists have criticized him.

Contents

Early Life and Studies

Growing Up and School

Brian Josephson was born in Cardiff, Wales, on 4 January 1940. His parents were Mimi and Abraham Josephson. He went to Cardiff High School. He has said that some of his teachers there really helped him. His physics teacher, Emrys Jones, introduced him to theoretical physics.

In 1957, he went to Cambridge University. He first studied mathematics at Trinity College, Cambridge. After two years, he found math a bit boring, so he decided to switch to physics.

Josephson was known at Cambridge as a very smart but quiet student. Another physicist, John Waldram, remembered hearing an examiner from Oxford, Nicholas Kurti, talk about Josephson's exam results. Kurti asked, "Who is this chap Josephson? He seems to be going through the theory like a knife through butter." Even before he finished his first degree, Josephson published a paper about the Mössbauer effect. He pointed out something important that other researchers had missed. Some famous physicists have said that Josephson wrote several papers that were important enough to make him famous in physics, even without his big discovery.

He finished his first degree in 1960. Then, he became a research student at the university's Mond Laboratory. His supervisor was Brian Pippard. An American physicist named Philip Warren Anderson, who also later won a Nobel Prize, spent a year in Cambridge in 1961–1962. He remembered that having Josephson in a class was "a difficult experience for a lecturer." This was because everything had to be exactly right, or Josephson would explain it to him after class.

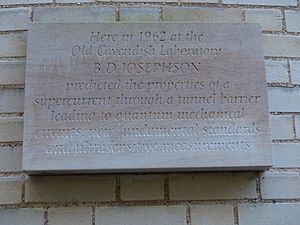

It was during this time, as a PhD student in 1962, that he did the research for the Josephson effect. In November 2012, the Cavendish Laboratory put up a special plaque on the Mond Building to honor this discovery. He was chosen as a fellow of Trinity College in 1962. He earned his PhD in 1964 for his research paper called Non-linear conduction in superconductors.

Discovering the Josephson Effect

Josephson was only 22 years old when he did the work on quantum tunnelling that earned him the Nobel Prize. He found that a supercurrent (an electric current that flows without any resistance) could "tunnel" through a very thin barrier. He predicted that:

- At a point where two superconductors meet, a current will flow even if there is no voltage (electrical pressure).

- When there is a voltage, the current will wiggle or "oscillate" at a speed related to the voltage.

- The current also depends on any magnetic field nearby.

This discovery became known as the Josephson effect. The special connection point is called a Josephson junction.

His calculations were published in a science journal called Physics Letters on July 1, 1962. The paper was titled "Possible new effects in superconductive tunnelling." His predictions were later proven true by experiments done by Philip Anderson and John Rowell at Bell Labs in Princeton. Their findings were published in January 1963.

Before Anderson and Rowell confirmed his work, another American physicist, John Bardeen, disagreed with Josephson's ideas. Bardeen had already won a Nobel Prize in 1956. He wrote an article in July 1962 saying that "there can be no such superfluid flow." This disagreement led to a discussion in September 1962 at a conference in London. When Bardeen, who was a very famous physicist, started speaking, Josephson, who was still a student, stood up and politely interrupted him. They talked about their different views.

The discovery of the Josephson effect led to many important things in physics. This includes the invention of SQUIDs. SQUIDs are Superconducting QUantum Interference Devices. They are used in geology to make very sensitive measurements. They are also used in medicine and in computers. In 1980, IBM used Josephson's work to build a test computer. This computer could be up to 100 times faster than the powerful IBM 3033 mainframe.

Winning the Nobel Prize

Josephson received several important awards for his discovery. These included the Research Corporation Award in 1969 and the Hughes Medal in 1972. In 1973, he won the Nobel Prize in Physics. He shared the award with two other scientists who also worked on quantum tunnelling. Josephson received half of the prize. This was "for his theoretical predictions of the properties of a supercurrent through a tunnel barrier, in particular those phenomena which are generally known as the Josephson effects." The other half of the award was shared by Japanese physicist Leo Esaki and Norwegian-American physicist Ivar Giaever.

Jobs and Roles

Josephson spent a year in the United States from 1965 to 1966. He was a research assistant professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. After returning to Cambridge, he became an assistant director of research at the Cavendish Laboratory in 1967. He stayed a member of the Theory of Condensed Matter group, which studies theoretical physics, for the rest of his career.

He was chosen as a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1970. In the same year, he received a fellowship from Cornell University. In 1972, he became a reader (a type of professor) in physics at Cambridge. In 1974, he became a full professor, a job he held until he retired in 2007.

Since the early 1970s, Josephson has practiced Transcendental Meditation (TM). In 1975, he became a visiting faculty member at the Maharishi European Research University in the Netherlands. This university is part of the TM movement. He also held visiting professor positions at other universities, including Wayne State University in 1983 and the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore in 1984.

Interests Beyond Mainstream Science

Early Interest and Meditation

In the late 1960s, Josephson became interested in the philosophy of mind. He was especially curious about the mind–body problem (how the mind and body are connected). He is one of the few scientists who believes that parapsychological phenomena (like telepathy or psychokinesis) might be real. In 1971, he started practicing Transcendental Meditation (TM).

Winning the Nobel Prize in 1973 gave him more freedom to explore less traditional areas. He started talking more about meditation, telepathy, and higher states of consciousness, even at science conferences. This sometimes annoyed other scientists. For example, in 1974, he suggested that scientists read the Bhagavad Gita and the work of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, who founded the TM movement. He also talked about special states of consciousness from meditation. One scientist reportedly shouted at him, "Nothing forces us to listen to your wild speculations."

Josephson said that Trinity College had a history of being interested in the paranormal. This meant he didn't immediately dismiss these ideas. He continued to explore the idea that there is intelligence in nature. He became more interested after reading Fritjof Capra's book The Tao of Physics (1975). In 1979, he started a more advanced form of TM. Josephson has said that meditation can lead to new scientific and spiritual insights. He also said that it made him believe in a creator.

Mind–Matter Unification Project

In the mid-1970s, Josephson became involved with a group of physicists at the University of California, Berkeley. This group was looking into claims about paranormal abilities. They called themselves the Fundamental Fysiks Group. They used ideas from quantum physics, especially Bell's theorem and quantum entanglement, to explore topics like action at a distance (where things affect each other instantly over a distance), clairvoyance (seeing things not present), precognition (knowing the future), and remote viewing (seeing distant places with the mind).

In 1976, Josephson visited California. He met other physicists who were interested in these topics. By 1996, he had started the Mind–Matter Unification Project at the Cavendish Laboratory. This project aimed to explore intelligent processes in nature. In 2002, he told Physics World: "Future science will consider quantum mechanics as the study of certain kinds of organized complex systems. Quantum entanglement would be one example of such organization, and paranormal phenomena another."

Views on Science

Josephson has often been described as one of physics' "more colorful figures." His support for ideas outside mainstream science has led to criticism from other scientists since the 1970s. Josephson sees this criticism as unfair. He believes it has stopped him from getting academic support.

He has often criticized "science by consensus," which means when scientists agree on something as true. He argues that the scientific community is too quick to reject certain ideas. He says, "Anything goes among the physics community – cosmic wormholes, time travel – just so long as it keeps its distance from anything mystical or New Age-ish." He calls this "pathological disbelief." He believes it causes academic journals to reject papers about paranormal topics. He has compared parapsychology to the theory of continental drift. This theory, proposed in 1912, was first resisted and laughed at. But later, evidence led to its acceptance.

In 2001, several physicists complained when Josephson wrote in a Royal Mail booklet that Britain was leading research into telepathy. One physicist said the Royal Mail had been "tricked" into supporting nonsense. However, another physicist pointed out that even mainstream physics has strange ideas, like parallel universes or time travel.

In 2004, Josephson criticized an experiment that tested a Russian schoolgirl named Natasha Demkina. She claimed she could see inside people's bodies. The experiment asked her to match six people to their medical conditions. She needed five correct matches to pass but only got four. Josephson argued that her four correct matches were still statistically important. He felt the experiment was set up for her to fail. One of the researchers, Richard Wiseman, said the experiment's rules were agreed upon beforehand.

Josephson's support for ideas like water memory and cold fusion has also made him well-known. Most scientists reject water memory as pseudoscience, but Josephson has supported it. Cold fusion is the idea that nuclear reactions can happen at room temperature. When Martin Fleischmann, a chemist who researched cold fusion, passed away in 2012, Josephson wrote a supportive article about him. Some scientists have suggested that Josephson's strong support for these ideas, despite mainstream scientific disagreement, is an example of a "Nobel disease." This is a term sometimes used when Nobel laureates promote ideas that are not widely accepted by the scientific community.

Awards and Honors

- £1,000 New Scientist prize, 1969

- Research Corporation Award for outstanding contributions to science, 1969

- Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1970

- Fritz London Memorial Prize, 1970

- Guthrie Medal (Institute of Physics), 1972

- Van der Pol medal, International Union of Radio Science, 1972

- Elliott Cresson Medal (Franklin Institute), 1972

- Hughes Medal, 1972

- Holweck Prize (Institute of Physics and French Institute of Physics), 1972

- Nobel Prize in Physics, 1973

- Honorary doctorate, University of Wales, 1974

- Elected as International Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 1974

- Faraday Medal (Institution of Electrical Engineers), 1982

- Honorary doctorate, University of Exeter, 1983

- Sir George Thomson (Institute of Measurement and Control), 1984

Images for kids

-

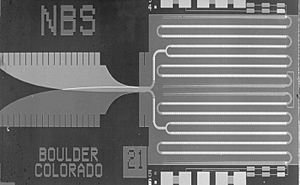

A one-volt NIST Josephson junction array standard. It has 3020 superconducting junctions.

See also

In Spanish: Brian David Josephson para niños

In Spanish: Brian David Josephson para niños

- Josephson voltage standard

- Josephson vortex

- Long Josephson junction

- Pi Josephson junction

- Phi Josephson junction

- List of Jewish Nobel laureates

- List of Nobel laureates in Physics

- List of physicists

- Scientific phenomena named after people

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |